May GLLI Blog Series: Japan in Translation, No. 28

What’s the significance of the numbers 18, 49, 82, and 183? If you answered that those are the numbers of light novels published in English annually from 2014-2017, you’re right. But I have a sneaking suspicion you are more likely thinking, “Wait, a ‘light’ novel? What’s that?”

The term originally appeared as a label in a Japanese pre-internet online community when the administrator, Keita Kamikita, decided to create a new “room” for people to talk about a certain growing strain of novels. Chatter like, “I bought [the latest volume]. Going to read it now,” followed by, “I read it. So-and-so survived. The scene where so-and-so is eating was good. I’m totally falling for her,” had been drowning out conversations like, “The way the author used x latest science in this SF way was really interesting.”

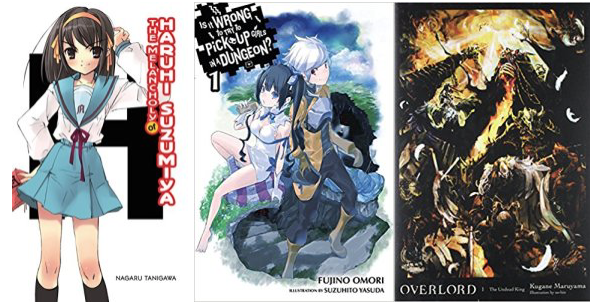

The shortcut I tend to use for explanation is “anime in book form.” That’s easy to understand for people who know about Japanese animation, because light novels often feature otaku tropes like magical girls, cat ears, cute little sisters, RPG (role-playing game) -inspired plots, and so on. It also points to how so many of them have—and so much of their growing popularity in English is driven by—anime adaptations. Some of the earliest light novels translated, such as the Haruhi Suzumiya series (by Nagaru Tanigawa and translated by Chris Pai), were naturally the basis of popular anime at the time. Still, linking them exclusively to anime is misleading.

Anime News Network correspondent Kim Morrissy says, “The simplest way of thinking about it is ‘if the publisher says it’s a light novel, then it’s a light novel.’ It’s all too common for people outside Japan to assume that any book which gets an anime adaptation must be a light novel when that’s not necessarily true.”

Writer Max Rivera, who wrote an article about common misunderstandings surrounding light novels, elaborates: “Light novels became a different kind of fiction, closely tied to otaku subculture, but also evolved into a social construct in and of itself. It’d be a disservice to lump them all together and just say they’re a ‘sub-genre of X or Y’; while they do belong to otaku subculture, their very nature stems from traditional literature.” As an alternative to traditional literature, in a way, they’re the bleeding edge of the scene.

Veteran translator and editor Paul Starr has a tongue-in-cheek personal taxonomy: “A light novel is any serial novel with too many single-sentence paragraphs.” He also comments on another critical element of a light novel: illustrations. “I think that the illustrator is of under-credited importance in the appeal of a light novel. It’s hard to imagine Danmachi (short for Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? by Fujino Omori and translated by Andrew Giappe) being the hit that it was without the design of Hestia being so successful at capturing the character’s appeal.”

So if the number of light novels is exploding, but the medium is still so niche in English that many people haven’t heard of it, who is translating them? Morrissy says, “I have noticed that a lot of translators who get brought on to do light novels come from a background in manga translation and aren’t necessarily familiar with light novels as a literary subculture on an intimate level. So, the light novel translators who are active right now are, in essence, exploring the frontiers and paving the way for a new form of literature in English. And that brings up questions for how translators should deal with these books. Do they stay closer to the conventions of manga and anime translation? Is the assumed target audience for these books always going to be anime fans?” It’s an important question because targeting anime fans involves assuming familiarity with Japanese culture and even Japanese, to an extent.

Light novels are published in Japan at a furious pace—an average of six per day last year according to Shuppan Geppou’s March 2018 issue—and if a series people want to read isn’t available, the fan (pirate) translators leap into action. When I started translating Kugane Maruyama’s Overlord, nine of the books in the series already had fan translations. There’s pressure to surpass them (without even looking at them), but also to work very fast. Between the tight deadlines and lack of chances for translators to work closely with their editors, quality issues can arise. “My hottest take after doing this for quite a while,” says Starr, “is that translating long works of serial fiction is incredibly difficult, and the industry as it works right now isn’t set up to ensure consistently good translations—realistically speaking, quality and accuracy falls solely on the shoulders of the translator, and translators vary hugely in their various strengths and weaknesses.” Maybe we can think of it as growing pains.

In any case, more books being translated means there are more translators out there—probably more than many people realize. In a way, it mirrors the way that the English translations available are still only the tip of the light novel iceberg. It’s encouraging to see publishers take chances on titles without anime adaptations. One I really enjoy is Kanata Yanagino’s The Faraway Paladin (illustrated by Kususaga Rin, translated by James Rushton, and published by J-Novel Club), a fantasy novel with a fresh take on magic.

Starr says his favorite to work on was Ayano Takeda’s Sound! Euphonium (illustrated by Nikki Asada and published by Yen On) which may or may not actually be a light novel “though it retroactively took on those trappings once Kyoto Animation did the anime adaptation.” Morrissy recently recommended (and de-recommended—ha!) titles in the hugely popular, ever-expanding isekai (other world) genre here. Rivera, who’s the biggest light novel fan I know, hesitates to make any recommendations at this point, noting how much is left to explore.

Following is a two-page excerpt from Carlo Zen’s The Saga of Tanya the Evil, vol. 2 (light novel), translated by Emily Balistrieri, courtesy of Yen On and Kadokawa Corp. After a ruthless Japanese human resources manager is murdered by a former employee, the self-proclaimed god, Being X, hopes to teach the manager a lesson in faith by reincarnating him into a world of magic as a girl. Using powers from Being X as well as knowledge from her previous life, Tanya works her way up the ranks in the Imperial Army aiming to attain a position safe in the rear. One of the biggest challenges in translating this series is expressing Tanya’s complicated dual consciousness.

Coming up in our last installment of Japan-in-Translation: Takami Nieda on her translation of Kazuki Kaneshiro’s Go

Coming up in our last installment of Japan-in-Translation: Takami Nieda on her translation of Kazuki Kaneshiro’s Go

Emily Balistrieri is a translator based in Tokyo. Her current translation projects include Carlo Zen’s The Saga of Tanya the Evil, Kugane Maruyama’s Overlord, The Witch’s Isle (developed by Cocosola), and Junk Head (directed by Takahide Hori). Follow her on Twitter at: @tiger.

Emily Balistrieri is a translator based in Tokyo. Her current translation projects include Carlo Zen’s The Saga of Tanya the Evil, Kugane Maruyama’s Overlord, The Witch’s Isle (developed by Cocosola), and Junk Head (directed by Takahide Hori). Follow her on Twitter at: @tiger.

David Jacobson organized this series on Japanese literature in translation. He is author of Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, a 2017 NCTE notable poetry book. A longtime journalist, David has written news articles and TV scripts that have appeared in the Associated Press, The Washington Post, The Seattle Times and on CNN and Japan’s NHK. Since 2008, he has worked with Seattle book publisher Chin Music Press. An experienced Japanese translator, he is on the board of the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative.

David Jacobson organized this series on Japanese literature in translation. He is author of Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, a 2017 NCTE notable poetry book. A longtime journalist, David has written news articles and TV scripts that have appeared in the Associated Press, The Washington Post, The Seattle Times and on CNN and Japan’s NHK. Since 2008, he has worked with Seattle book publisher Chin Music Press. An experienced Japanese translator, he is on the board of the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative.

And in case you missed it…

May 1: Roger Pulvers on Ishikawa Takuboku (Japan-in-Translation, No. 1)

May 2: Kathryn Hemmann on outsider stories in contemporary literature (Japan-in-Translation, No. 2)

May 3: Deborah Iwabuchi on memorable translations (Japan-in-Translation, No. 3)

May 4: Eve Kushner on kanji’s punning potential, part 1 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 4)

May 5: Eve Kushner on kanji’s punning potential, part 2 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 5)

May 7: Translator roundtable on Shiba Ryōtarō’s Ryōma!, part 1 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 6)

May 8: Translator roundtable on Shiba Ryōtarō’s Ryōma!, part 2 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 7)

May 9: Librarian Ash Brown on manga in translation (Japan-in-Translation, No. 8)

May 10: Excerpt from Mori Eto’s Dive!! (Japan-in-Translation, No. 9)

May 11: Tony Malone on translations of Natsume Sōseki (Japan-in-Translation, No. 10)

May 12: Poet Michael Dylan Welch on translating haiku (Japan-in-Translation, No. 11)

May 14: Smithsonian BookDragon’s Favorites, part 1 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 12)

May 15: Smithsonian BookDragon’s Favorites, part 2 (Japan-in-Translation, No. 13)

May 16: Sally Ito on Misuzu Kaneko’s Compassionate Imagination (Japan-in-Translation, No. 14)

May 17: Frederik Schodt on The Four Immigrants Manga (Japan-in-Translation, No. 15)

May 18: Stone Bridge Press Publisher Peter Goodman (Japan-in-Translation, No. 16)

May 19: Melek Ortabasi on Japanese Literature as World Literature (Japan-in-Translation, No. 17)

May 20: Selected Japanese Picture Books by Andrew Wong (Japan-in-Translation, No. 18)

May 21: Murakami translator Jay Rubin (Japan-in-Translation, No. 19)

May 22: Zack Davisson on translating sound effects in comics (Japan-in-Translation, No. 20)

May 23: Translator showdown: where manga meets the novel (Japan-in-Translation, No. 21)

May 24: Kirkus YA Editor Laura Simeon on cultural messages in Japanese picture books (Japan-in-Translation, No. 22)

May 25: Q&A with Translator Cathy Hirano on Nahoko Uehashi’s The Beast Player (Japan-in-Translation, No. 23)

May 26: Strong women, soft power by Ginny Tapley Takemori (Japan-in-Translation, No. 24)

May 27: War in Japanese children’s literature by Sako Ikegami (Japan-in-Translation, No. 25)

May 28: Translating Kadono Eiko by Lynne E. Riggs (Japan-in-Translation, No. 26)

May 29: Roland Kelts on Monkey Business (Japan-in-Translation, No. 27)

4 thoughts on “The Vast Light Novel Universe — by translator Emily Balistrieri”