Written by Angela Erickson

Those of us who work or live in a world of books know that perhaps the richest terrain for graphic novelists is memoir and biography. As I type this, I can picture the covers of Maus, Persepolis, and Dragon Hoops — some of the graphic memoirs that I regularly press into the hands of teenage readers.

It raises the question: what is it about this particular form that works so well? The interplay between text and image allows graphic novelists to layer emotion, memory, and meaning in ways that prose alone cannot. The structure invites ambiguity. It asks readers to slow down. And for stories that deal with trauma or silence, the kinds of stories that are difficult to tell directly, the graphic memoir creates a space that is at once intimate and interpretive.

These are not tidy narratives. They are textured, layered, and sometimes contradictory. For a thoughtful reader, the gaps between panels often hold as much meaning as the images themselves. At the same time, the immediacy of illustration makes the emotional stakes visible. Readers are not just told what happened, they are invited to feel what it might have been like.

Perhaps that is why graphic novels in translation about displaced people are especially powerful. These are stories far removed from the average teen reader’s experience, but graphic storytelling creates an emotional bridge, not only across cultures and contexts, but across the reader’s own limits of understanding. And if reading is, among other things, empathy training, then these books offer an essential kind of education.

Below are several graphic novels in translation that offer such a bridge.

Grass (2019) by Keum Suk Gendry Kim

Nominated for the ALA Alex Award in 2020, Grass by Keum Suk Gendry Kim and translated from the Korean by Janet Hong tells the story of Lee Ok-sun, a Korean teenager who was trafficked to China during World War II and forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military as a “comfort woman.”

It is a story that demands to be told, and the format here serves it in unexpected ways. The heavily inked panels convey weight, restraint, and gravity. The violence and horror are present, but the images are suggestive rather than explicit. In prose, this story might need to be more graphic to be clear. In this visual storytelling, the gravitas is there but not the abject horror or salaciousness. This reversal is worth considering, particularly with mature teen readers.

For a longer review of this book, see this blog post by Lauren Elliott a year ago during #INTYALITMONTH 2024.

You can buy a copy of Grass here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

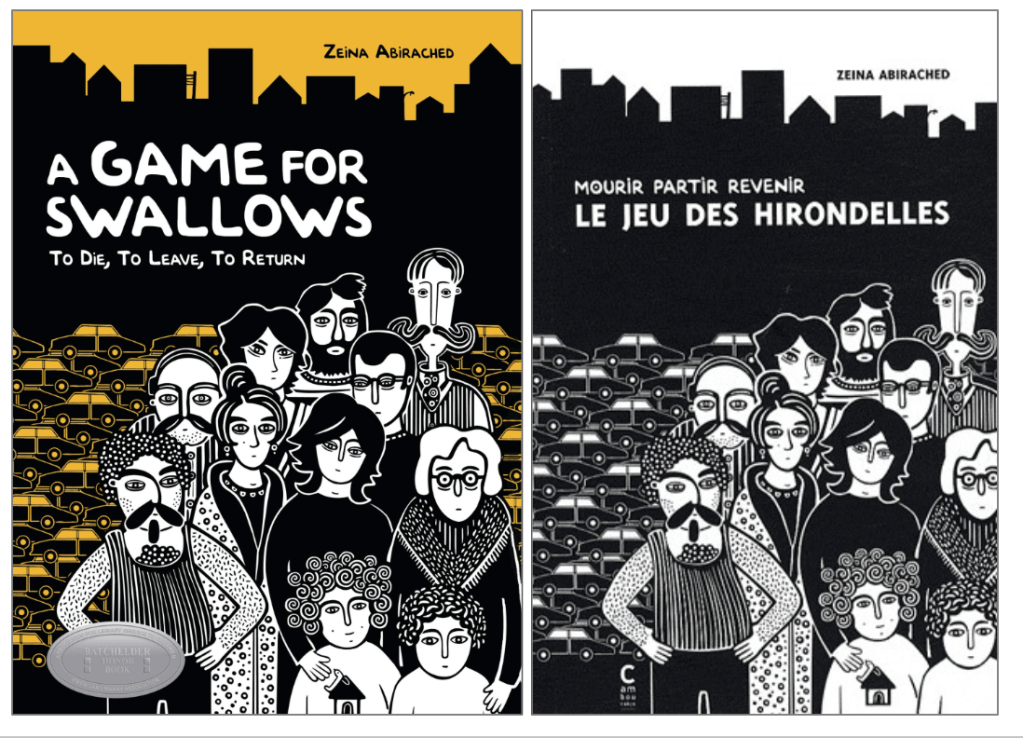

A Game for Swallows: To Die, To Leave, To Return (2012/2022) by Zeina Abirached

Told through the voice of a child living in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War, A Game for Swallows: To Die, To Live, to Return by Zeina Abirached and translated from French by Edward Gauvin uses stark black-and-white illustrations to great effect, much like Persepolis. (Note: the 2022 Expanded Edition features a new illustrated afterword.)

What stayed with me most after reading this was the sense of constrained space. How far someone can safely move in a city under siege, and how communication is paramount but strained in conflict zones. The narrative is modest in scale but powerful in implication.

For classroom use, this book opens up rich opportunities for inquiry-based learning. There are so many things students may want to ask: How do people survive war when they cannot flee? How does a child understand danger? What makes a home feel safe?

A Game for Swallows has been mentioned on the GLLI blog quite a few times — click here to search for all those instances.

You can buy a copy of A Game for Swallows: Expanded Edition here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

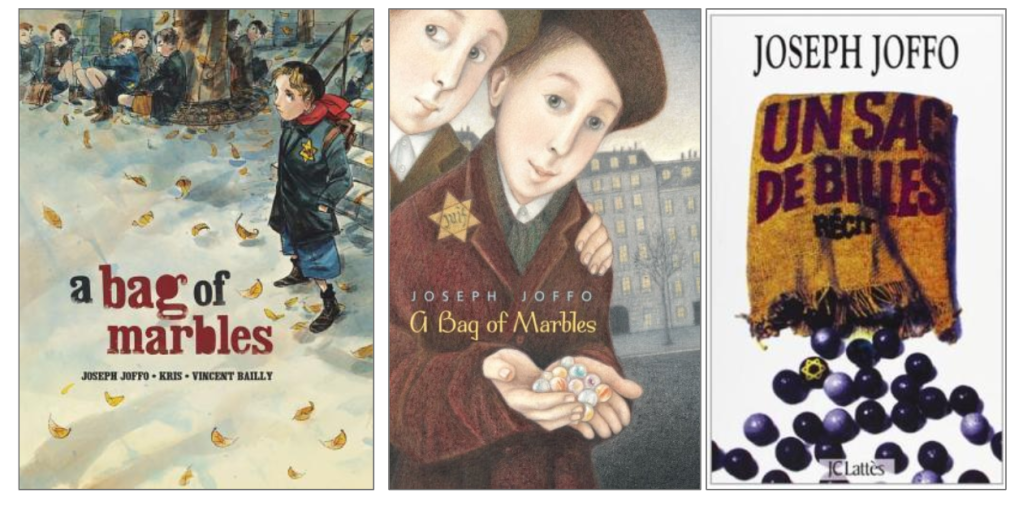

A Bag of Marbles (2012) adapted from the memoir by Joseph Joffo

This beautiful graphic adaptation of Joseph Joffo’s 1973 memoir, A Bag of Marbles, was illustrated by Vincent Bailly, scripted by Kris (Christophe Goret), and translated from the French by Edward Gauvin. (Note: the memoir was originally translated into English in 1977 by Martin Sokolinsky.) It traces the journey of two French Jewish brothers fleeing Nazi-occupied France. Maurice and Joseph are sent on their perilous journey by their parents, and what unfolds is both an adventure and a reckoning. The illustrations shift between warmth and danger, capturing a blend of childish resilience and adult terror as they are forced to face difficult truths about war, identity, loss, survival, and growing up.

After reading this, I will be recommending A Bag of Marbles (both the prose memoir and the graphic adaptation) as a compelling counterpoint to The Diary of Anne Frank — one child trapped in a single room, the others surviving by moving constantly through a world that wants them gone.

There have been two French film adaptations of Joffo’s classic book — one in 1975 directed by Jacques Doillon, and another in 2017 directed by Christian Duguay (watch trailer here).

You can buy a copy of A Bag of Marbles here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

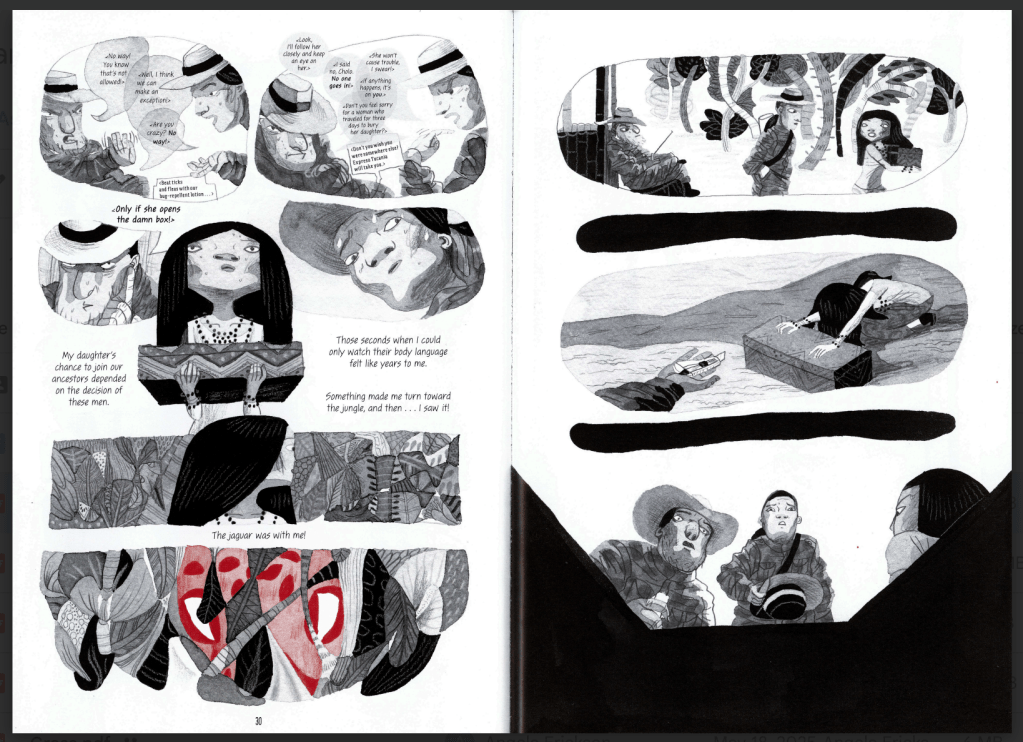

Amazona (2022) by Canizales

I am sneaking into this group of memoirs and biographies Amazona by Canizales, translated from the Spanish by Sofía Huitrón Martínez and Russell Alwes. It is fiction, but it reads like truth. Dedicated to “those who have had to flee”, this story follows Andrea, a 19-year-old Indigenous woman who returns to the Amazon to bury her infant daughter and to surreptitiously document the illegal mining that led to her community’s forced displacement. The illustrations are lush and devastating. Andrea is both mourner and witness. Her journey feels spiritual and political at once.

While reading, I found myself wishing I had known about Amazona when I taught Year of the Weeds by Siddhartha Sarma (see this GLLI review last year during #INTYALITMONTH), which centers on the Gond people in India resisting mining on their ancestral lands. These texts, while from different continents, raise similar issues about power, memory, and who has the right to land and to grief.

For a longer review of Amazona, see this blog post by Klem-Mari Cajigas in 2022 as part of World Kid Lit Wednesday.

You can buy a copy of Amazona here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

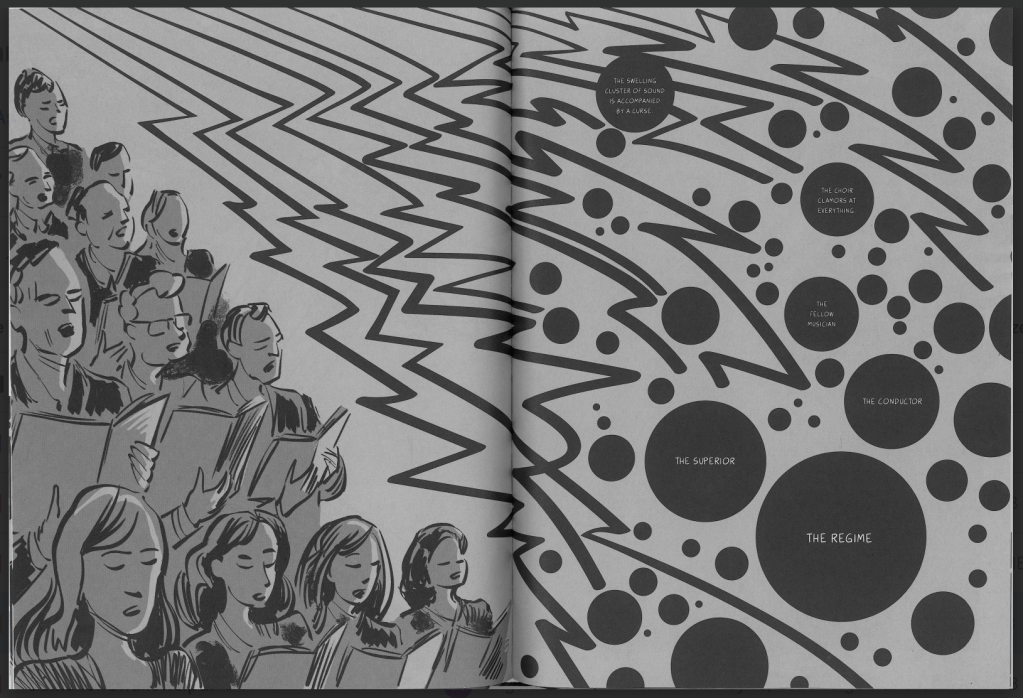

Between Two Sounds: Arvo Pärt’s Journey to His Musical Language (2024) by Joonas Sildre

Between Two Sounds by Joonas Sildre and translated from Estonian by Adam Cullen tells the story of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, tracing his life from youth through his family’s deportation to Siberia. While less overtly framed as a story of displacement, Between Two Sounds captures the emotional and artistic dislocation caused by exile and authoritarian control. Pärt’s music, known for its stillness and clarity, becomes a kind of resistance.

The structure of the book, moving between sound and silence, order and chaos, mirrors the disruptions of forced movement. The narration blends personal history with a deeper meditation on creative expression under pressure. It would not appeal to young teens, but to older students interested in music or life under an oppressive regime, it is a quiet, beautiful piece of work.

You can buy a copy of Between Two Sounds here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

Final Thoughts

These graphic novels offer more than just context and information. They create a bridge between the reader and experiences that might otherwise feel distant or abstract. Through carefully rendered images and narrative choices, they invite readers to sit with complexity, to ask questions, and to see the human story behind the headlines. For educators, they offer space for real inquiry. For all readers, they offer perspective and connection.

Angela Erickson is a former head of Middle School English who currently works as the Head of Libraries at United World College (Dover campus) in Singapore. She is interested in how educational leadership, curriculum design and workshop pedagogy can be integrated to create a school culture of reading, thinking and writing. For the past few years, she has been working to create systems to articulate classroom and departmental libraries with the central school libraries to support the needs of all readers. She currently teaches one section of “The Imperfect Art of Living” for the Innovation Academy Online. When she is not reading, Angie enjoys mountaineering and playing the cello badly (to the consternation of her next-door neighbors).

Katie Day is an international school teacher-librarian in Singapore and has been an American expatriate for almost 40 years (most of those in Asia). She is currently the chair of the 2025 GLLI Translated YA Book Prize and co-chair of the Neev Book Award in India, as well as heavily involved with the Singapore Red Dot Book Awards. Katie was the guest curator on the GLLI blog for the UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021 and guest co-curator for #IndiaKidLitMonth in September 2022.

One thought on “#INTYALITMONTH: Graphic Novels of Displacement ”