The past seems to bubble up to the surface more frequently and picturesquely in Lithuania than in other places. The country is famous for its deposits of amber, fossilized tree resin. These golden nuggets are brought up from deep underground, sometimes containing bits of long-dead insects and plants.

Lithuania is also the burial ground of more recent, human history. For the past two summers, archaeologists in the capital city of Vilnius have been excavating the ruins of the city’s Great Synagogue, damaged in World War II, demolished during Soviet times, and now buried underneath a primary school. The same team has pinpointed the location of additional mass graves in the Ponary killing site, where the congregation of that synagogue and tens of thousands of other Jews were murdered. Not far from the site of the Great Synagogue, scientists have been studying mummies in the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit. And also close by, the crypt beneath the Cathedral of Vilnius, where the remains of kings and queens were revealed during a flood in the 1930s, is a popular tourist attraction, as are the buttons and scraps of uniforms of Napoleon’s soldiers, who died in Vilnius during the disastrous retreat from Moscow in 1812, now on display in the National Museum.

Maybe in Vilnius nothing really remains hidden forever. A stroll away from the National Museum, the Dominican Church, and the Cathedral, and not all that far away from Ponary, there was another treasure trove, hidden in yet another church. Thousands of documents and books from Jewish libraries, archives, and synagogues were hidden from Nazi looting by a small group of men and women, at the risk of their lives. After the war, they were forced to hide the materials again, this time from the new Soviet occupiers of Lithuania. They turned for help to a courageous, non-Jewish librarian, Antanas Ulpis, head of the Book Chamber of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, located in the requisitioned Church of St. George. He and a handful of trusted staff members hid the materials in nooks and crannies and under piles of debris and kept the secret for forty years. Only with the arrival of glasnost did Jews in the West learn of the existence of the trove, long believed to have been destroyed.

Hidden in the Book Chamber were the last earthly remains of the Ashkenazic East European civilization that was all but completely wiped out by Nazi genocide and now survives only in fragments scattered around the world. Among the treasures are thousands of books from the famed Strashun Library, including rare Hebrew books and Yiddish books. There are also tens of thousands of documents, including literary works, letters, memoirs, theater posters, photographs, pamphlets, political and religious tracts, and communal records. Many of the materials are in Yiddish, once the everyday language of the over 200,000 Jews who lived in Lithuania before World War II, but barely spoken or understood by the few thousand Jews who live there today.

These books and documents are now being cataloged, conserved, and digitized by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in partnership with the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania and the Lithuanian Central State Archives. A large proportion of the hidden documents and books came from the collections of YIVO, which is now located in New York. There, in its archives and library, are tens and thousands of the books and millions of pages of the documents that the Nazis did succeed in looting. After the war, they were recovered in Frankfurt-am-Main and with the help of the U.S. Army, returned to YIVO in its new headquarters in the United States.

The collection on both sides of the ocean will be reunited online in a search portal that is due to launch at the end of October 2017 at https://vilnacollections.yivo.org . The full text of books and archival folders will be available to researchers as PDFs. This is the first step to making them accessible to a readership that goes beyond scholars proficient in Yiddish. Not only are there many books never translated from Yiddish into other languages, but also manuscripts that have never been published. These Yiddish literary works run the gamut of high art to children’s literature and populist genres, such as first aid manuals, and other how-to guides.

By Roberta Newman (Director of Digital Initiatives, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

Writers and publishers had trouble keeping up with a voracious Yiddish readership in the 1920s-30s, a brief period flowering for Yiddish literature and schools in Eastern Europe. So it was also an era in which Jewish children were increasingly exposed to Yiddish translations of children’s literature in other languages. Among the books now being digitized by the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Collections project is this 1920 Yiddish translation of Bingo, the Story of a Dog, a section from Ernest Thompson Seton’s 1898 Wild Animals I Have Known, the most popular of his many books of animal fiction. (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York)

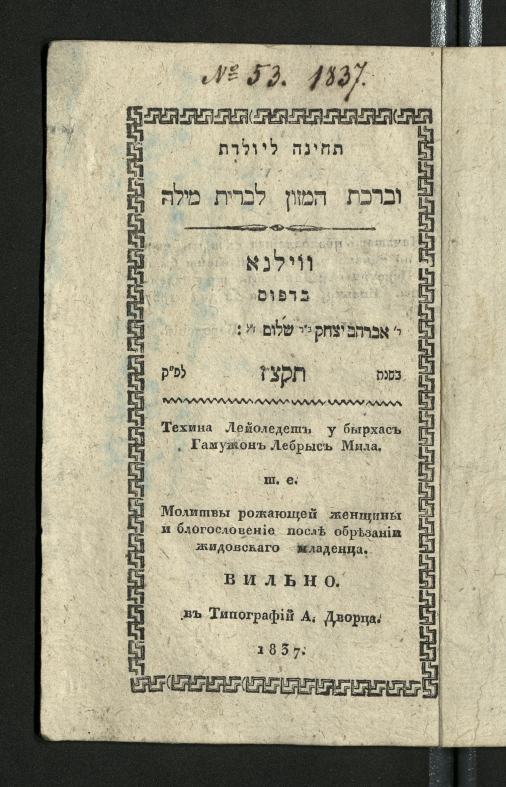

There were few female authors in the early history of Yiddish literature. A notable exception to the rule is the genre of tkhines (supplications), private devotions and prayers, which were intended primarily for use by women and were often written by women. This book from the National Library of Lithuania combines a collection of tkhines related to childbirth with the grace said after the celebratory meal following a bris (circumcision ceremony). It was printed in Vilna in 1837 and its second title page notes that its author is “Sore [Sarah] the midwife, daughter of our teacher Kadesh.” In addition to prayers to be said before and after childbirth, there are also prayers that can be said by pregnant women and even barren women. (Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania)

Wow! These findings are incredible. Thank you for such an interesting and informative post.

LikeLike

These are amazing. Thank God for kind souls that kept these treasures safe.

LikeLike