By Allan Pinto & Kim Tyo-Dickerson

Introduction to a Queer, Black Brazilian Reading Life

by Allan Pinto

During my time in middle and high school, I can barely remember Black authors being mentioned in the annual book lists given out by the school. Many Black and queer authors used to be called “autores malditos” or “cursed authors” for being the ones who explored subjects that challenged the status quo imposed by the Brazilian dictatorship, a regime that plagued the country from 1964 to 1985. A good introduction to this topic can be found in the 2004 article written by Domício Proença Filho, “A trajetória negra da literatura brasileira”/ “The Trajectory of Black People in Brazilian Literature”.

Growing up reading books written by white authors that were meant to appeal to a white audience had created in me an impression of being invisible or alien to what should be my own culture and social context as a young adult. The books that addressed queer topics, the ones that were not censored or hidden, normally dealt with those topics through the lenses of sociological or scientific studies. The first popular and successful “queer book” I remember being published in Brazil in 1986, was Devassos no paraíso:A homossexualidade no Brasil, da colônia à atualidade by João Silverio Trevisan; translated as Perverts in Paradise, translated by Martin Foreman.

Even so, it was pretty much an account of how these individuals lived or survived from the colonial times until the 20th century in Brazil. There were no humanized or relatable characters. And it was still non-fiction.

Meanwhile, Black authors and Black stories were still not making it to the mainstream. Those authors were considered niche and their books were basically read by university students or by people who participated in antiracist movements.

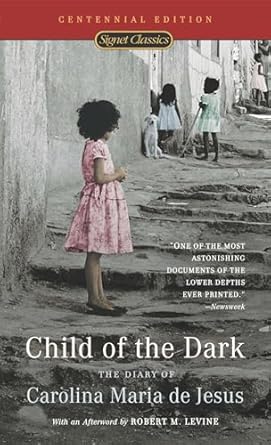

An important example of this is the life and work of Carolina Maria de Jesus. She was a pioneering Afro-Brazilian woman writer whose candid and powerful voice brought international attention to the lives of economically disadvantaged communities, called “favelas,” in mid-20th-century São Paulo. Born in rural Sacramento, Minas Gerais, she had limited formal education but taught herself to read and write. While raising three children and working as a scrap paper collector in the Canindé favela, she chronicled her daily struggles with suffering, hunger, and despair, keeping her observations in diaries written on discarded paper.

Her most renowned work, Quarto de Despejo: Diário de uma Favelada (1960), translated into English as Child of the Dark by David St. Clair, offers a raw and unfiltered account of life in the slums. For de Jesus, even small things, like a child’s birthday, were eclipsed by poverty:

“My daughter Vera Eunice’s birthday. I intended to buy her a pair of shoes. But the cost of food prevents us from fulfilling our wishes. Nowadays we are slaves to the cost of living. I found a pair of shoes in the trash, washed them and mended them for her to wear” [Source]

Her story centers her view of the favela as the city’s dumping ground, one where race, gender, and class impacted residents on a daily basis. Her legacy resonates with a voice that represents the reality of the Afro-Brazilian experience:

“Half a century after Brazil formally abolished slavery, written in the 1930s, her anthology still educates a nation about the plight of Black women and men: the ills of material poverty, hunger, their denied right to housing, as well as the resilience, intellect, and strength of the Afro-Diasporic woman. In sum, Carolina Maria de Jesus educates Brazilians about Brazil.” [From a 2024 article by Igor Soares on the occasion of Women’s Day].

Upon release, Child of the Dark became an immediate bestseller in Brazil, selling 10,000 copies in its first week, and was eventually translated into over a dozen languages, reaching readers in more than 40 countries. The importance of her work to Brazilian literature, and her initial success, did not ensure that she was fairly compensated for her work and she had no rights to international translations. De Jesus and her work fell into obscurity, and suffering from asthma her entire life, she died in poverty all but forgotten.

De Jesus wrote as an act of resistance within a hegemonic literary scenario, white and colonial, that lasted almost unchanged until the early 2000’s. That is because in 2003 the first left wing president in the history of Brazil was elected. This created a radical shift in the Brazilian cultural way of expression and social representation as a whole due to a number of affirmative actions put in place by that government. The most important one being the creation of university entrance quotas for Black, indigenous and low income people. This allowed the appearance of a fresh wave of intellectual, artistic and academic production in the country. From that moment on, Black, indigenous and queer stories and their histories became more evident and accessible to the whole population. The internet also played a great role in disseminating the work done by authors, artists, and academics who were from the African diaspora, queer culture, indigenous heritages, favela citizens, and, in particular, female authors.

From this pivotal moment, it became possible to offer Young Adult readers important books that resonated with them by means of the intersections between sexuality, gender, race, and class, allowing for the creation of diverse characters who represented the threads of the true Brazilian social fabric.

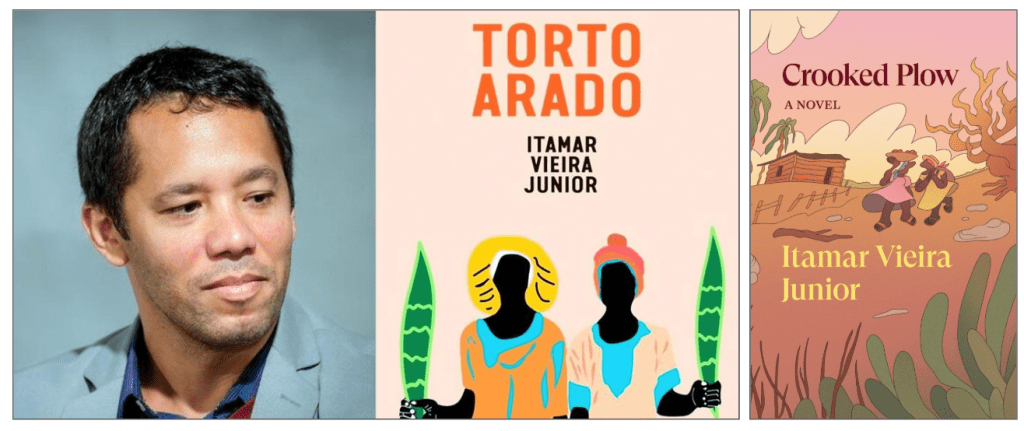

One powerful example of this shift toward more representative storytelling is Torto Arado (2019) or The Crooked Plow (2023) by Itamar Vieira Junior and translated into English by Johnny Lorenz, a novel that weaves together race, class, ancestry, and land in a deeply personal and historical narrative that continues to echo through generations. It was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2024.

Torto Arado tells the story of a family whose ancestors were enslaved people, and even after slavery was abolished in Brazil, they remained on the same land, living under the same system, on the same farm. It’s very similar to what happened in my own family. For example, my surname is Pinto, and that comes from the family who once enslaved my ancestors. When slavery ended, many families like mine continued working for their former masters. Over time, as people had to get official documentation, many didn’t have surnames, as those memories of who they were back in Africa were lost after 300 years of slavery. So it became common to adopt the surname of your former master. That’s what happens in Crooked Plow, and that’s why the book resonated so deeply with me. I could see my own family dynamic reflected in the story.

From Africa to Brazil and Back Again: Exploring the African Diaspora Fiction and Nonfiction

by Allan Pinto and Kim Tyo-Dickerson

Another flourishing area in Brazilian publishing is books centering the African diaspora and which have particular appeal for Young Adults. An exciting example of representation of the diaspora in fiction is the cross-cultural anthology Do Índico e do Atlântico: contos brasileiros e moçambicanos [From the Indian Ocean and Atlantic Ocean: Brazilian and Mozambican Short Stories] with Brazilian authors chosen by Vagner Amaro and Mozambican authors chosen by Dany Wambire.

This book is a literary exchange project that brings together short stories by male and female writers from Brazil and Mozambique. Its purpose is to serve as a vehicle for expanding knowledge about the literature produced by each country’s authors, expanding and connecting both Brazilian and Mozambican authors to new readers. This project created a collection that strengthens cultural ties in a fertile territory such as literature and promotes an innovative literary cultural exchange between the two countries.

While Do Índico e do Atlântico highlights the shared cultural and linguistic ties between Brazil and Mozambique through original short stories in Portuguese, this literary dialogue expands even further in The Deep Blue Between (2020) by Ghanaian author Ayesha Harruna Attah which was translated into Brazilian Portuguese by Valéria Almeida as O imenso azul entre nós (2021). The Deep Blue Between was a White Ravens 2021 selection and featured in Nadine Bailey’s collection for GLLI “Celebrating Brazil.”

This novel takes the West African origin stories and the histories of enslaved peoples in the grip of colonial powers and reclaims them through a narrative that incorporates Brazilian characters and settings. It follows twin sisters, Hassana and Husseina, who are separated during a slave raid and embark on divergent journeys, one to Accra, Ghana, and the other to Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Despite being torn apart and subjected to the brutalities of colonialism, both sisters engage in acts of resistance throughout their journeys. Hassana, in Accra, resists the forces of erasure by preserving her memories and spiritual traditions, refusing to let her identity be stripped away. Husseina, living in the Afro-Brazilian community of Bahia, navigates forced assimilation while finding power in Yoruba-based religions and local solidarity networks.

Their pursuit of knowledge, connection to ancestry, and spiritual resilience become forms of defiance against the colonial systems that seek to define and contain them. The narrative delves into the cultural and spiritual landscapes of both West Africa and Brazil, highlighting the enduring bonds of sisterhood and the complexities of identity across continents. In doing so, The Deep Blue Between frames survival, memory, and self-reinvention as radical acts of resistance against historical erasure and displacement.

A Brazilian nonfiction text furthers this language of resistance and celebration of Afro Brazilian history is the beautiful Adinkra – Sabedoria em símbolos africanos [Adinkra: African Wisdom Symbols] by Elisa Larkin Nascimento and Luiz Carlos Gá brings together the ideograms of the writing tradition of the people of the Akan linguistic group of West Africa.

An accessible nonfiction, richly illustrated text that can be explored by English readers using a camera translation tool, this fascinating collection can inspire Young Adults interested in West African symbology and Visual Arts. Adinkra is a Ghanaian symbolic language representing a philosophical and aesthetic universe based on the human body and figures of animals, plants, stars and other objects. The drawings incorporate, preserve, and transmit aspects of the history, philosophy, values and sociocultural norms of this rich African culture. These symbols are present in various forms of cultural expression in Brazil like architecture, religious temples, clothes patterns and body paintings and tattoos. These uses can be interpreted as acts of resistance connecting formerly enslaved Afro-Brazilian people to their African heritage.

Allan writes: Growing up in Brazil, I would walk through middle-class neighborhoods and see certain tiles on houses, or iron fences with intricate designs, not realizing that those were actually African symbols. The patterns of the imagery and decoration on these buildings were deeply inspired by African motifs and cultural references. They told the Afro Brazilian story. The book sheds light on this hidden presence, showing how African culture has been embedded in architecture and design, even if people didn’t know where it came from. The book highlights how these symbols are used today, on cloth patterns, in branding, and in urban landscapes. It’s a powerful way of understanding how African culture is everywhere, often taken for granted, and how architecture in Brazil can become a means of communicating the value of that heritage.

Hiding in plain sight, these symbols became powerful forms of resistance technology. It reminds me of other cultural practices that maintained Afro Brazilian heritage. Take capoeira, for example.

On the surface, it looks like a dance, and that’s exactly how it survived. Enslaved Africans in Brazil used it as a way to train and prepare for self-defense and rebellion without raising suspicion. It was a disguised form of martial arts, masked in rhythm and music, so they could not be punished for “fighting.” Capoeira was not just a cultural expression, but a survival strategy. It was a way to reclaim agency in a violent, oppressive system. Through movement, rhythm, and community, capoeira became a powerful tool of resistance.

And it wasn’t just in the body, but also in the spirit. In colonial Brazil, enslaved Africans were forbidden to practice their religions. So, they found a way to hide their sacred traditions in plain sight. That’s where the alignment of Catholic saints to the Orisha came in. Each Orisha was given a Catholic counterpart, Iansã with Saint Barbara, for instance, so they could continue their spiritual practices under the guise of Catholic worship. From the outside, it looked like conversion, but really it was preservation. It wasn’t the Church making those connections; it was the people themselves finding ways to hold onto their beliefs. They weren’t just accepting Catholicism, they were outsmarting it. It was a resistance naming, a spiritual camouflage, and to me, that’s one of the most brilliant forms of cultural resilience we’ve inherited.

Towards an Inclusive and Representative Afro Brazilian Literary Tradition with YA Appeal

by Allan Pinto

In contrast to my own Young Adult reading experiences, in the last two decades or so the Brazilian publishing industry has begun to recognize and publish more and more Black and queer authors, books that can be found at any bookstore in the country. These books are being submitted to the main book fairs, for example in the very important Bienal Internacional do livro de São Paulo / São Paulo International Book Biennial, a trend-setting publishing event for the whole of Latin America.

Although having gained a more secure space in the publishing world, queer, indigenous and Black authors still fight some backlash from the conservative and fascist forces that persist in the country. A prime example was the banning of the book O avesso da pele / The Dark Side of Skin by Jeferson Tenório and translated into English by Bruna Dantas Lobato. This text was banned from public schools and public libraries in several states of Brazil despite being Prêmio Oceanos Nominee (2021) and winning the Prêmio Jabuti for Romance Literário (2021).

The Dark Side of Skin tells the story of Pedro, a young man who investigates the past of his father, who was murdered in a police operation. The work explores themes of racism, violence, and the fight for rights, addressing Brazilian society in a critical way. Through Pedro’s eyes, readers witness the normalization of police brutality in marginalized communities and the indifference of the justice system. The novel also delves into the intergenerational trauma experienced by Black families in Brazil, as Pedro’s search for answers becomes a form of resistance and self-affirmation. His reflections on the dangers of simply existing in a Black body in Brazil serve as a chilling reminder of how racial violence is embedded in everyday life.

Like Pedro’s story, other Brazilian YA novels also confront urgent social issues through deeply personal narratives, particularly those highlighting queer voices and the challenges they face in contemporary society. Você tem a vida inteira by Lucas Rocha, translated by Larissa Helena as Where we go from here, tells the story of three young people whose fates become intertwined after one of them is diagnosed with HIV. This book has gained popularity among YA readers and has even been internationally awarded here on the 2021 Global Literature in Libraries Initiative’s Translated YA Book Prize.

Another very good example of a text that talks about our Blackness is the poetry collection Só por hoje vou deixar o meu cabelo em paz (new edition 2022) by Cristiane Sobral. She wrote this beautiful book, and even though I don’t think there is an official translation, I translate the title as Just for Today, I’ll Let My Hair Be.

In her poetry, she talks about her hair and appearance with pride. She treats her hair as a cultural manifestation, as a reaffirmation of Black beauty. What I love is how she puts her hair as a character, one that assumes a position of Blackness in society.

The poet spares no expense and wit when it comes to mortally wounding those who practice discrimination, prejudice, sexism, racism and homophobia…Using the same lyrical material, she sometimes fiercely condemns those who dare to disdain the hair of black men and women. She writes about the policy of discrimination that engenders Brazilian society and that maintains a structural and structuring situation of colonialism, in disguise, in an attempt to deceive many people. [Quote by Professor Rosalia Diogo via Google Translate].

Just for today

I’ll leave my hair alone

For 24 hours I will be able

To take away

The European style sunglasses I wear

Facing the light

Just for today

Só por hoj

Vou deixar o meu cabelo em paz

Durante 24 horas serei capaz

De tirar

Os óculos escuros modelo europeu que eu uso

Enfrentar a claridade

Só por hoje

[Diogo via article on

literafro – The portal of Afro-Brazilian literature, Faculty of Letters of the Federal University of Minas Gerais:}

That really shows the evolution we’ve had. I believe we need to talk about this with our young readers—to show them this evolution, and that we should keep on reading and keep on valuing our Black, Indigenous, and queer authors.

In Conclusion: Progress and Hope for Young Adult Publishing in Brazil

by Allan Pinto

The current climate in Brazilian publishing has not only gifted young adult readers with the possibility of reading fiction and nonfiction works that tell the stories of neglected or persecuted members of society, but has also allowed long forgotten books and authors to resurface and establish themselves in a place of relevance and importance. Reprints and new editions of Carolina Maria de Jesus’ books, are thankfully being published to wide acclaim.

Fortunately, there is currently a healthy movement towards diversity and representativity in the YA books and the Brazilian editorial market as a whole that strives to bring humanity, compassion and talent to all types of readers without leaving behind younger ones who, not so many years ago, had only a very limited and highly restrictive choice of stories, with dominant narratives focused on white-washed, cultural elite’s representations of reality.

Talking about Brazilian Literature is, for me, not always easy or possible to do in a more analytical and impersonal fashion. That’s the conclusion I arrived at while getting prepared to collaborate on this article.

Allan Pinto is a dedicated international educator with a Bachelor’s degree in Languages and Literature from the Federal University of Juiz de Fora. He is currently pursuing a Master’s in Library and Information Science at Queen’s University and works as a Library Assistant at the International School of Amsterdam. With over 15 years of experience as an ESL teacher in Brazil, where he taught K-12 students and was actively involved in theater as an actor, producer, and stage director, Allan brings a diverse skill set to his current role. His passion for reading and education is deeply rooted in his identity as a Black, queer, Latino man, fueling his commitment to social justice. He firmly believes that education and shared knowledge are crucial for building a more fair and equitable society. As he often quotes Brazilian icon Caetano Veloso, “…gente é feito para brilhar…” (people are meant to shine). (htt)

Kim Tyo-Dickerson is Head of Libraries and Upper School Librarian at the International School of Amsterdam. Kim has a Master of Library and Information Science from Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York. She also has a Master of Arts in English, with a concentration in 17th and 18th century British Literature, and a Bachelor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies with a Minor in Women’s Studies, from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. With over 20 years of experience in school libraries in North America, Europe, and Africa, Kim brings a global perspective to her work. Her practice is deeply informed by her Ethiopian American family and is grounded in social justice, with a focus on diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging. Kim was the guest editor for the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative’s #WorldKidLitMonth #DutchKidLit in September 2021. She also contributed to GLLI’s UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021, writing on Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender Equality. Kim’s languages are English, German, and Dutch, and she continues to explore multilingual intersections of language, literature, and identity. Connect with Kim on Bluesky and LinkedIn. Kim’s pronouns are she/her.

Katie Day is an international school teacher-librarian in Singapore and has been an American expatriate for almost 40 years (most of those in Asia). She is currently the chair of the 2025 GLLI Translated YA Book Prize and co-chair of the Neev Book Award in India, as well as heavily involved with the Singapore Red Dot Book Awards. Katie was the guest curator on the GLLI blog for the UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021 and guest co-curator for #IndiaKidLitMonth in September 2022.

One thought on “#INTYALITMONTH: Brazilian YA: An Exploration of a Postcolonial Literary Tradition by and for the Diaspora”