By Kim Tyo-Dickerson and Maria van Lieshout

Introduction

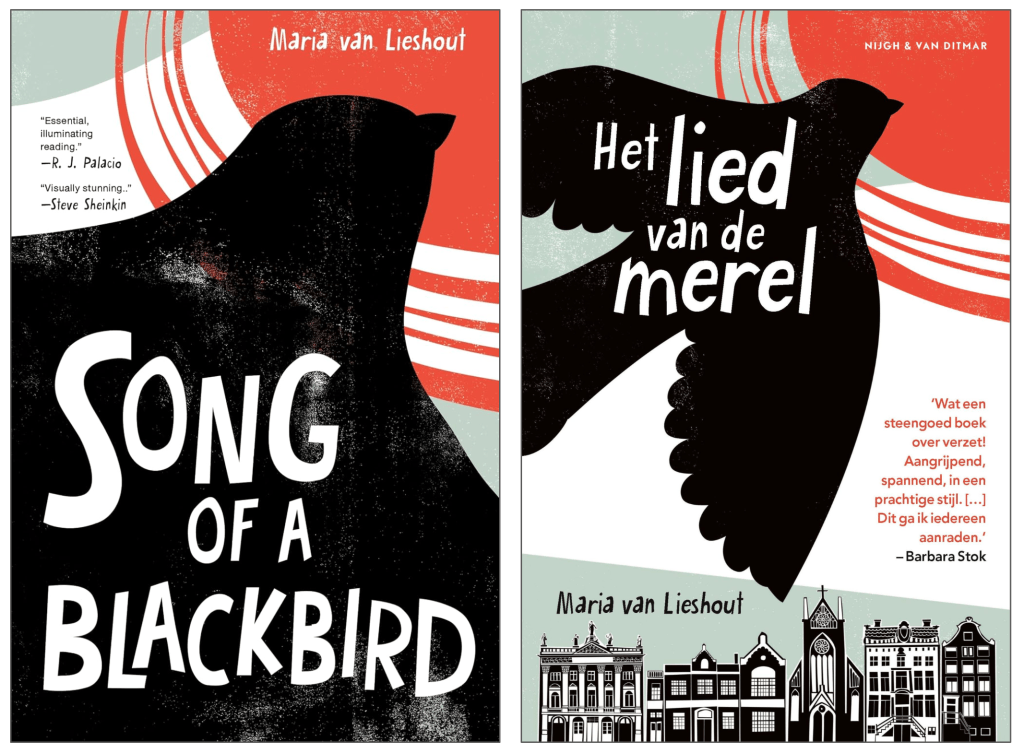

It was a privilege to speak with author and illustrator Maria van Lieshout about her powerful Young Adult graphic novel debut, Song of a Blackbird / Het lied van de merel, a story that has already earned five starred reviews in the United States for its “exploration of grief, family, and the vital importance of artistic expression” (Publisher’s Weekly review).

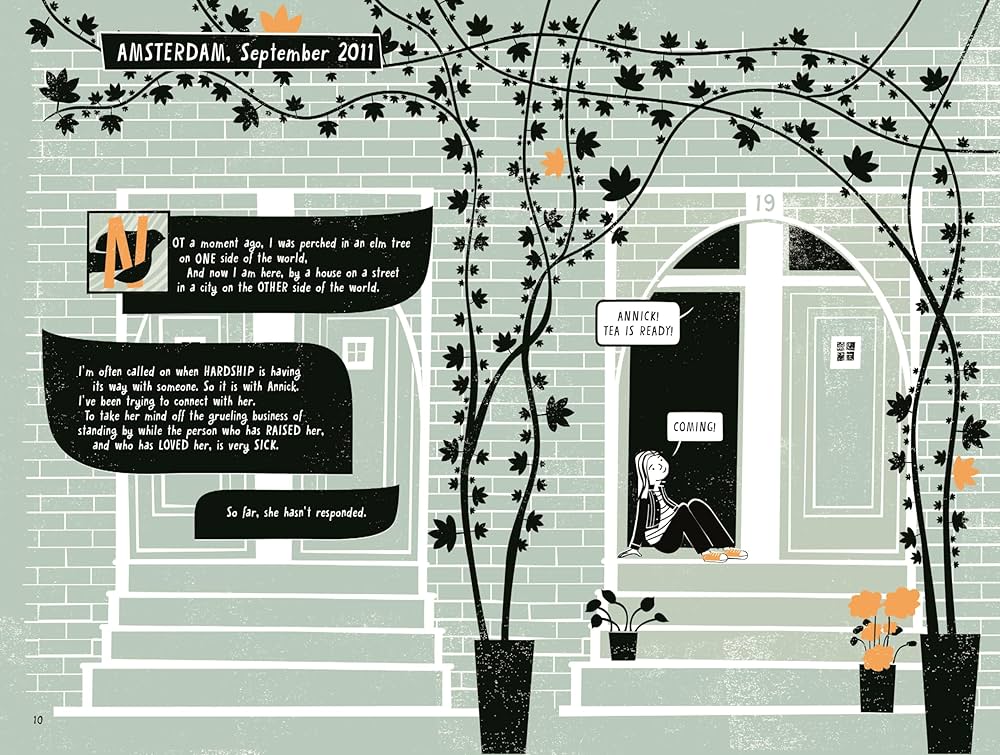

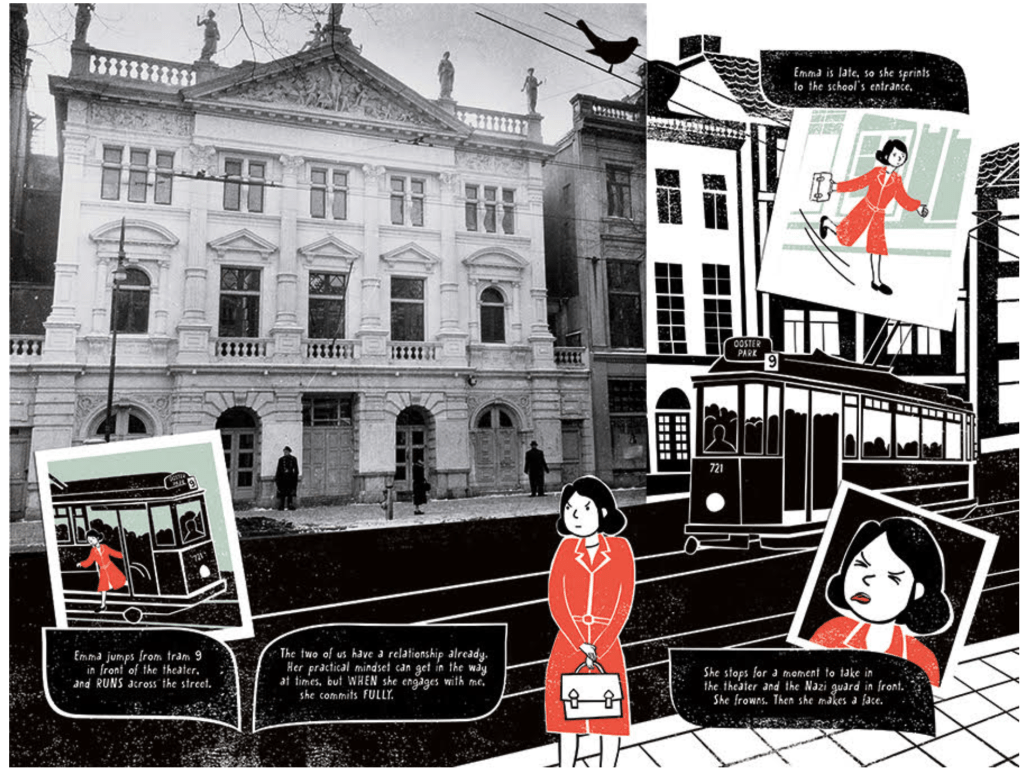

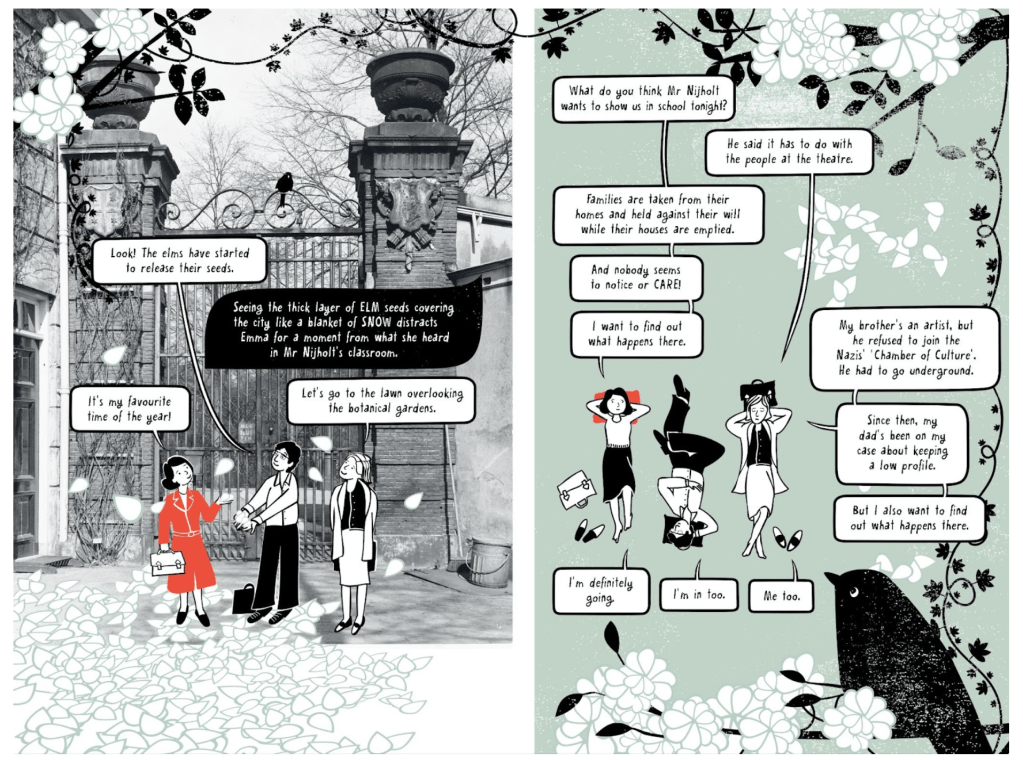

In this dual-timeline narrative, van Lieshout weaves together two pivotal moments in a Dutch family’s history: Annick’s journey in contemporary Amsterdam in the fall of 2011, as her grandmother faces a terminal illness and long-hidden family truths surface; and Emma’s life during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in the spring of 1943, when danger, resistance, and courage unfold in the shadow of war.

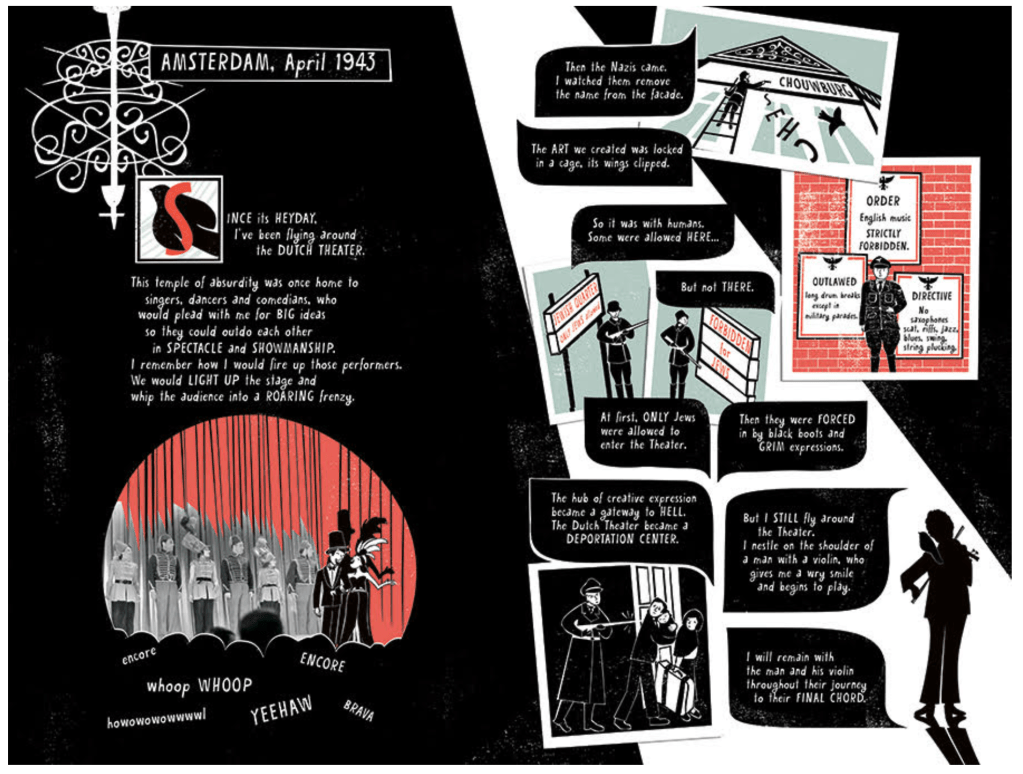

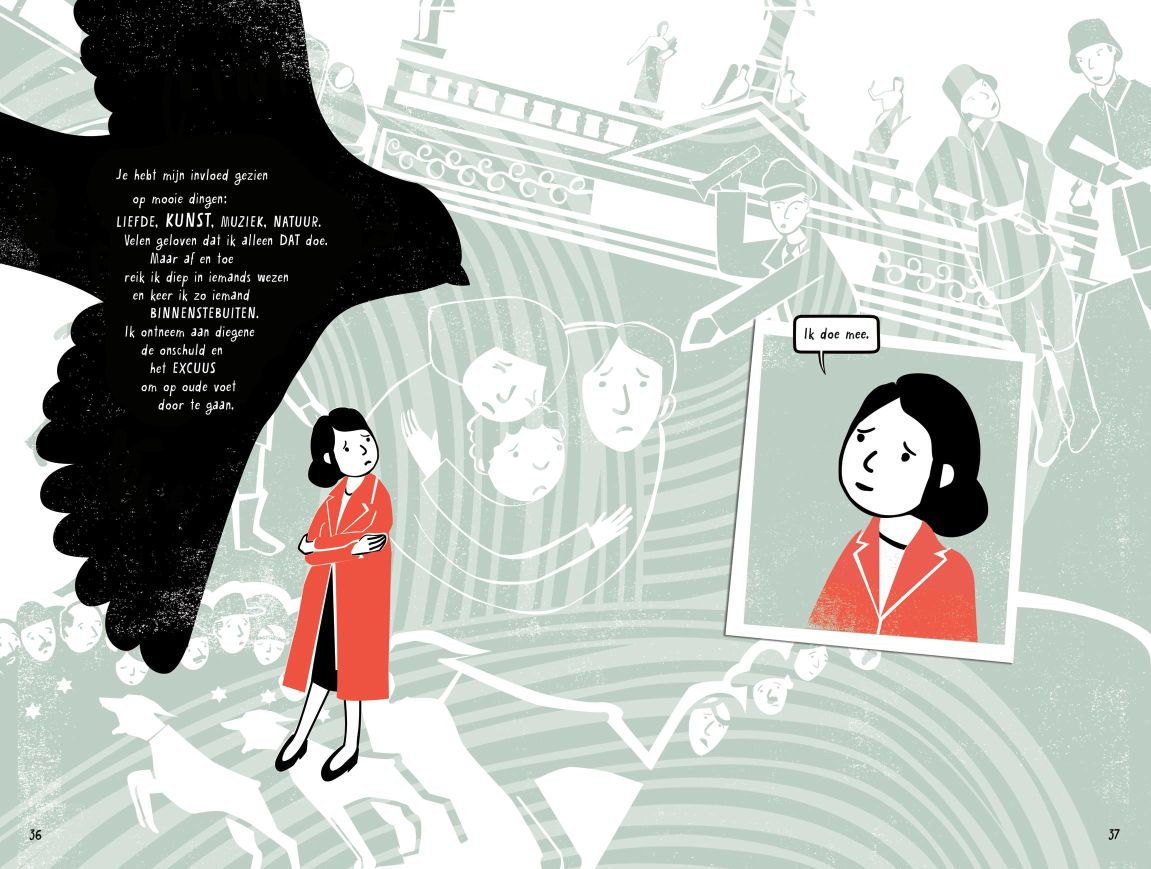

What binds these stories together is the haunting, omniscient song of an Amsterdam blackbird, a symbolic narrator perched among the city’s elm blossoms, who sees across generations and time. The blackbird’s observations and interventions are represented by black silhouettes, white text, and dynamic, black-winged thought balloons flying in and out of panels.

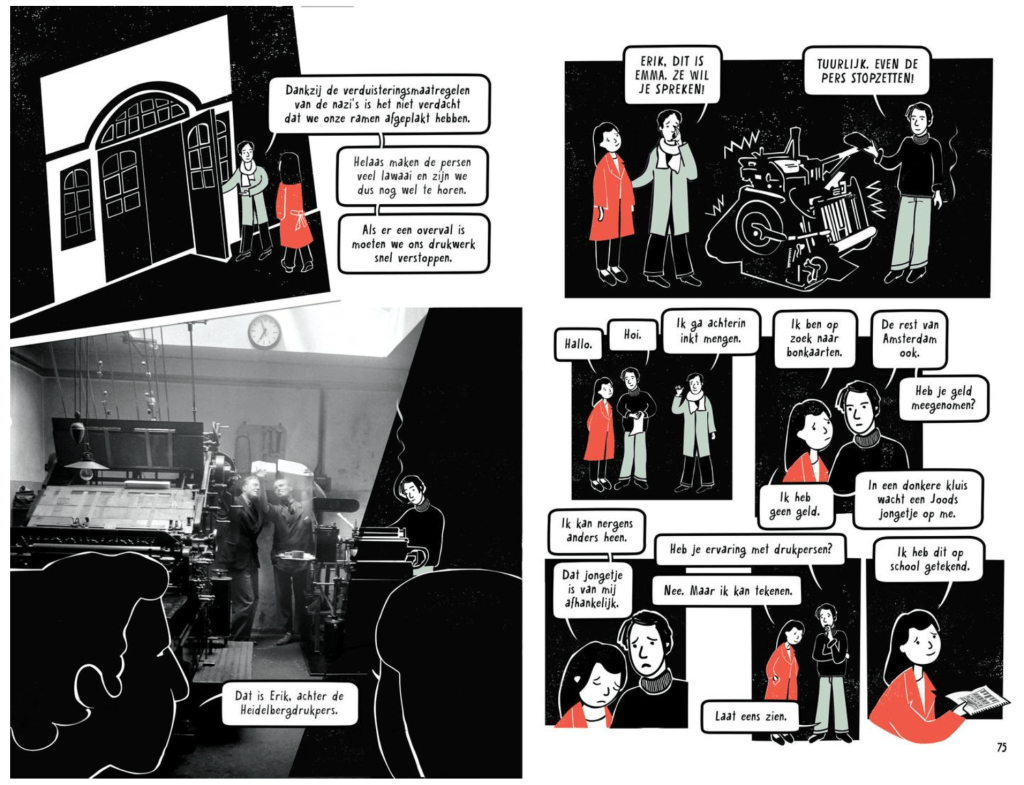

Van Lieshout uses archival research to integrate period photos into her text, creating collages that seamlessly interject historical accuracy and the unique geography of Amsterdam within her striking graphic panels. Through this interplay of physical media and graphic novel conventions, she explores themes of creating art as resistance and acts of moral courage, harnessing the power of memory and intergenerational trauma, and capturing the importance of critical thinking in the face of propaganda. These themes work together to create a graphic novel that is not just a historical account, but a contemporary reflection on art, activism, and remembrance.

Our conversation took place across continents: Maria, speaking from her home in San Francisco, and I, from Voorburg, a village beside The Hague in the Netherlands. We delved into the book’s remarkable bilingual journey, discussing how van Lieshout wrote two distinct versions, in English and Dutch, and navigated both publishing worlds. She shared insights into her research process, her creative decisions, and how she shaped the narrative to speak authentically to readers on both sides of the Atlantic.

What emerges from our conversation is a portrait of an artist who honors history through art, and who, like her blackbird, sings across generations in a voice that insists on truth, beauty, and hope.

Interview with Maria van Lieshout on 5 May 2025, Dutch Liberation Day

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: Thank you so much for speaking with me about Song of a Blackbird for the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative’s fifth annual International Young Adult Literature Month! It’s fascinating to learn more about how your family history, and some surprising discoveries in your grandparents’ home in Amsterdam, helped inspire this powerful story, especially the connection to the Dutch resistance during World War II. That hidden past clearly shaped your moving exploration of how art and survival are intertwined.

I’m especially excited to be talking with you today, on May 5, which is Liberation Day in the Netherlands, marking the end of the Nazi occupation in World War II. This theme of liberation is so central to your story, both in the words and the images.I’d love to hear more about the unique publishing journey of Song of a Blackbird in the U.S. and Het lied van de merel in the Netherlands.

You essentially created two different versions of the same story, in two languages and for two different cultures. I’ve read a bit about that process, but I’m curious to know more. What kinds of artistic, cultural, or language choices did you have to make along the way? And how did working with two publishing worlds influence your storytelling?

Maria van Lieshout: You are the perfect person to interview me about this because you are so uniquely positioned to understand both aspects of it. I get a lot of questions about it during my talks because people are fascinated by the fact that I am Dutch and I translated it into Dutch myself. But most people do not have the knowledge of the language and the culture in the same way you do. So, you have that special understanding. I’ve been in the United States for a long time and my writing career has always been here. so I feel very confident writing in English. I would say at this point in time I feel more confident writing in English than I do in Dutch even though Dutch is my mother tongue and it’s the first language I ever spoke.

When you are from a different culture, you have an objectivity, you have a distance that I believe makes you a better storyteller. So in 2011 when my grandmother passed away and we found documents among her belongings about the years under Nazi occupation, I started reading and learning about this bank heist that had taken place. I was blown away by it.

I wondered, why is it that I don’t know this story, and why does nobody else know this story? But having that American perspective, I immediately understood the appeal of that story in a way that perhaps Dutch people may not because they might be looking at that story through a slightly different lens. I immediately knew, there’s something I want to do with this. But I did not know exactly what, so I started talking to my literary agent, and I told him that I had come across a story I was inspired by and that I wanted to do something with it. And he encouraged me to write the story.

At the time I didn’t know whether it was going to be a novel written in prose or an illustrated novel, or even for what audience. As I learned more, I became incredibly inspired by the role that artists and women had played. That wasn’t the angle most books, documentaries and movies had taken. Those were written from the perspective of the male bankers. To be honest, my grandfather was a banker, and his friend Frits was a banker. So that’s the world I’m from and in the beginning that’s very much how I looked at the story too. Until the ME TOO movement happened a few years ago where all of a sudden we started questioning dominant narratives and I was like “I really want to write this from a different perspective…” I wanted to write the story from the perspective of a female artist.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: This is a very carefully considered reframing of this story as you began drawing from your family’s history in combination with current world events and evolving understandings of how history has traditionally been told. How did living and working in the United States help you find that new perspective on the World War II narrative?

Maria van Lieshout: Having a somewhat detached, objective lens helped me. I knew it was going to be easier for me to write this in English and that it would be an easier story to sell in the US. I felt I could explain the concept to my agent or to a potential publisher using sound bites like “the biggest bank heist” knowing that it would land the way I wanted it to land.

Studying the bank heist using Dutch non-fiction books left me with a profound respect for how complex and layered that act by the Resistance was. There were so many people, Resistance groups, printers, artists, and banks involved in pulling it off. I realized it would be challenging to write a non-fiction book about it. Since it was important to me to make the story accessible to a broad, young audience, I knew I had to fictionalize it.

But I wanted to do this in a way that honored the people who inspired the story. I believe the Dutch tend to often opt for non-fiction when writing about history and World War II, and tend to stay closer to the original narrative when writing historical fiction than in American historical fiction. So opting for a fictional approach to this historical event, taking the creative liberties that I did, was a bit of a risk.

Writing it in English for an American audience gave me the distance I needed from the historical account to focus on writing the best story I could. It allowed me to write in service of the story, not in service of historical accuracy. Once I had achieved that in English, it was easier for me to translate and adapt it into Dutch.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: That makes a lot of sense, as writing in English provided you with creative distance before returning to the story in Dutch. What happened once you were back in the Netherlands? How did being physically in the country influence your process as you worked on both editions at the same time?

Maria van Lieshout: I temporarily moved to the Netherlands summer 2022. I was still working on the US edition. So I worked on the American edition for another year from the Netherlands, until summer 2023, when I turned it into my US publisher and started working with them on the edits for roughly six months. At the same time, I started translating it into Dutch with the help of my Dutch publisher. I had a fantastic editor with Nijgh & Van Ditmar, which was good because I sure needed help writing it in Dutch.

It was great to work in both languages simultaneously because there were things that came up in the process with one editor that I could go and adjust in both languages. I had an excellent American editor who did a lot of fact-checking using Google Translate to make sure that everything I’d written was factual. She was able to point out several factual inaccuracies so I was able to take that information and take it to my Dutch publisher for adjustment in the Dutch edition too. Dutch publishers are so much smaller that they have to do much more heavy lifting where FirstSecond had a whole battery of people working on this book. So it was a really sort of mutually beneficial process.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: It sounds like working across both languages, and with very different publishing teams, really shaped the final versions of the book in meaningful ways. That makes me wonder: how did you think about the relationship between the two editions themselves? Were you aiming for a direct translation, or something more tailored to each audience?

Maria van Lieshout: I believe that both stories are not translations. I’m very uncomfortable with the word translation because I feel like I wrote the best story in English for an American audience and then I took that story and translated it into Dutch for a Dutch reader. So I wanted to write the best story for the Dutch reader, not necessarily create the most accurate translation of the original text. And an example of that is if you string together all the drop caps throughout the text, there’s a secret message. It’s actually the theme of the book, it reads, “Inspiration is everywhere. Fly with it.”

When I translated the book into Dutch, I wanted to use the same device. But of course, if I was going to stay very close to the original text, that would not have worked. I had to take some creative liberties in my translation and every first or first two sentences I actually had to change them to accommodate it. In Dutch if you string together all the drop caps it reads “Inspiratie is overal. Laat je meevoeren.”

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: I love knowing this secret message within the text! This is a great example of how you were able to create a separate, uniquely Dutch edition of Blackbird as you worked with your two publishers. I am wondering if at some point early on you ever considered having a Dutch translator?

Maria: Yes, I had initially wanted to go with a Dutch translator, but my Dutch publisher convinced me to translate it myself. I now know that was the right decision. I would have regretted it if the book had been translated by someone else.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: That’s really interesting, especially given how the book is being positioned so differently across countries. As you moved between languages and publishing contexts, did your sense of who the book was for begin to shift? And how do you see young readers in particular responding to the story and its emotional weight, especially through the visual elements?

Maria van Lieshout: In the Netherlands, the book is marketed as an adult book, while in the US the book is marketed as a Young Adult title. It recently came out in Australia where it’s also marketed as a Young Adult title. It’s going to be coming out in Germany next year and it’s going to be marketed as a Young Adult title. I do believe that Young Adults are the heart of the target audience and now that I’ve been going to schools in the US to talk about the book and I see how students react and how they come up to me and the personal stories they tell me about their family history, it’s just a confirmation to me that is the right audience. I’m hopeful that the Dutch edition will find that audience eventually in the Netherlands.

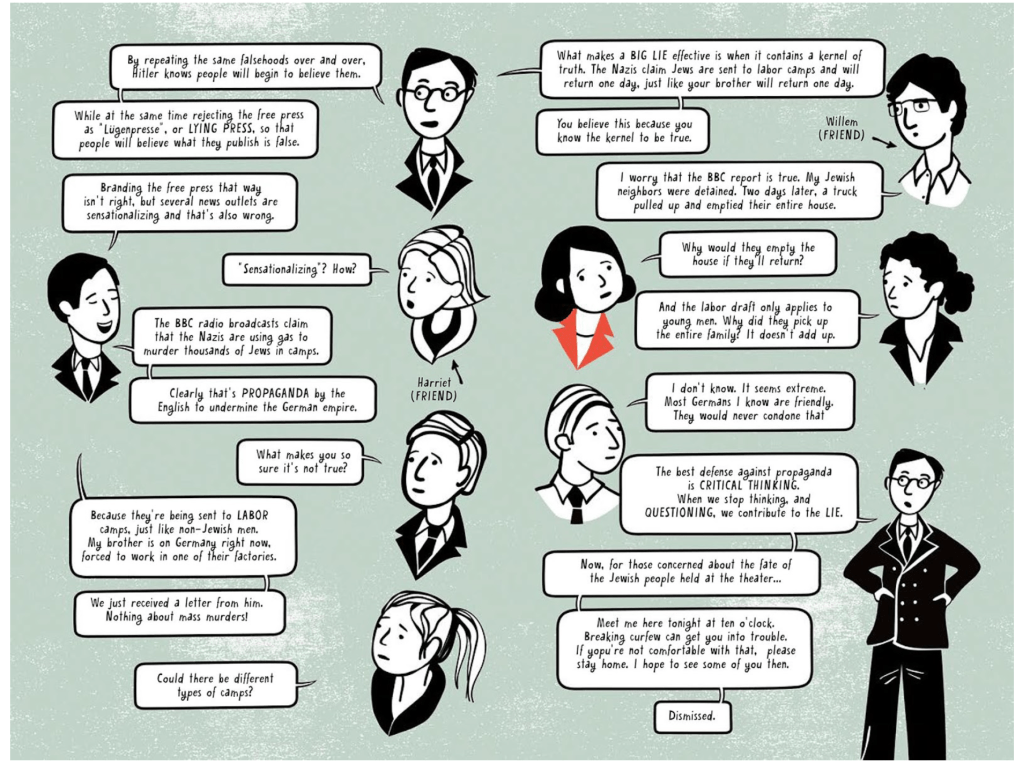

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: The Young Adult characters in Blackbird feel like real agents of change, embodying the book’s driving idea: Fight hate. Make art. That message, along with the early classroom scene, really struck me. It reads like a miniature play, this tight, dynamic space where a teacher and his students debate propaganda, resistance, and the role of critical thinking. Having taught information literacy and critical thinking myself, I was so impressed with how nuanced and layered that scene felt. The street art throughout the book reinforces those ideas too, how art can provoke, challenge, and reframe the world around us.

That early exchange in the classroom, was that moment meant to serve as a kind of framing device for the themes of propaganda, resistance, and the larger role of art through printing, forgeries, and even Street Art? Am I reading that right?

Maria van Lieshout: Yes, you’re absolutely reading that correctly. Thank you so much for picking up on that. The classroom scene where the students discuss the power of propaganda happens fairly early in the book. It is a pivotal scene that sets the stage for much of what comes after. I knew that there was a lot of ground to cover in this novel and I realized I had to frame this pretty early in the book or else it would run too long. What better environment to do this than a classroom, right? A classroom is a place of learning, a place of debate, a place of trying out different theories and so I felt that that was an ideal environment for some of these ideas to be expressed.

Many people now question, how did that happen that 104,000 Jewish people were deported to camps and killed in gas chambers? I now know that this happened because people were as confused and as misguided and as influenced by propaganda as we are today. Some people knew as early as 1943 about the gas chambers because the BBC broadcast I refer to on that page is in fact an actual broadcast that was the first broadcast ever about the gas chambers. But many did not listen to radios because radios were requisitioned by the Nazis. Some people had clandestine radios they would secretly listen to and they might have heard it. So there were some people who had heard about it, and who were very concerned but then there were also other people who said, “No, that’s ridiculous. Germans would never do that.”

So, I wanted to re-create that environment where all these different opinions were being aired, because I believe that was what the reality was at the time. And I wanted to frame that early on in the story so that the readers would understand the environment all these events were happening within.

Face-to-face debates with people who think differently are wonderful and important. Let’s not delete, unfollow, or cancel people we disagree with. Let’s find out what we have in common and start there. Let’s get out of our echo chambers and debate again!

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: The framing really works, highlighting young adult risk-taking, the emotional and moral intensity young people carry, which is so central to Blackbird. Their choices feel immediate and personal, not abstract, and that authenticity really resonates, especially with teen readers who often live at the edge of split-second decisions.

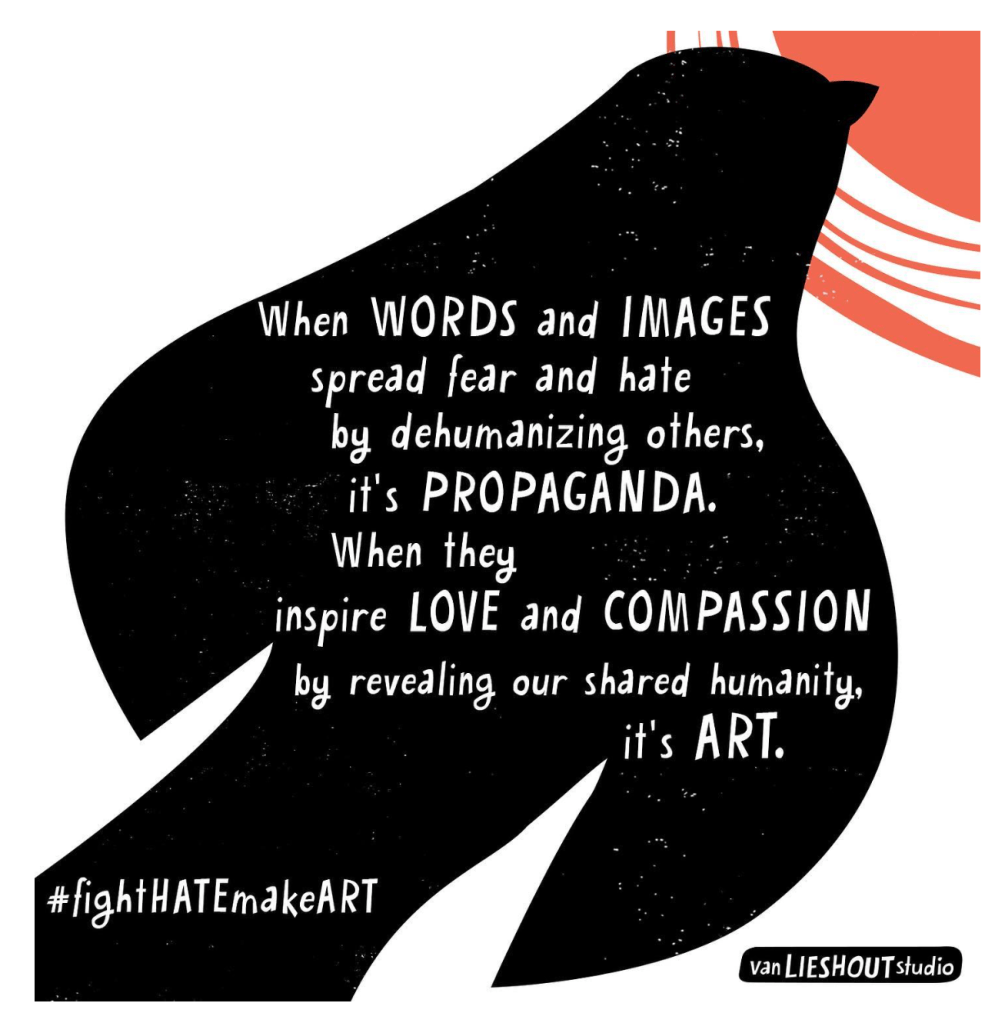

You’ve talked about how the mantra “Fight hate. Make art” distills the heart of your story. How did you arrive at that phrase, and why did it feel right not only for your characters, but also as a message to your readers. especially the young ones just beginning to understand the power of their voices and actions?

Maria van Lieshout: When I visit schools, I tell the story of how I found my grandparents’ documents and I show photographs of the people that my story is inspired by, including a photo of my grandfather’s friend who was arrested by the SS, along with a young woman named Hanneke Eikema. Hanneke was only 19 years old at the time and she became a political prisoner. And I tell kids, “this woman was only a few years older than you guys are today and yet here’s what she did. And yet here she became a political prisoner in the Nazi prison.” And that is usually the moment in the presentation where I see all their eyes grow big.

Fight hate, make art, is a distillation of the theme of the book. I discovered these brave artists and printers who had been so clever in forging these treasury bills and identity papers and ration coupons, saving thousands of lives through their art. So that’s when I decided I wanted the theme of my book to be the power of art to fight hate. That’s ultimately at the heart of this book. I am a firm believer in that. I believe that art has tremendous power in many ways: It opens our eyes to the beautiful diverse work world that we live in. But art and creativity is also an effective tool of resistance. I found that the armed resistance often gets all the attention because it’s very present.

But I learned it wasn’t the most effective form of resistance exactly because it attracts a lot of attention and often members of the armed Resistance were the ones that were arrested by the Nazis and they were the ones that were turned into examples. They were the ones who were publicly executed and called terrorists and called criminals much in the way that we see that happening today. They were singled out and they are made into examples. To make everyone afraid. But the more effective form of resistance was the quiet resistance that uses art and expression and words and images and creativity to rescue people. And ultimately that was the message of my book and that’s the message Eric has tattooed on his chest, and Emma has written on her tombstone. That’s the anthem: Fight hate. Make art.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: While reading Blackbird, I felt a connection between the artists and printers of the 1940s and today’s street artists. Both work in public, visual mediums, often outside official systems, to challenge authority, spread truth, and inspire resistance. Even though their tools and styles are different, they share this powerful, democratic drive to speak up and reach people where they live. It makes me think about how art, especially subversive or unsanctioned art, becomes a kind of witness to history.

Did you see the character of Koenji, and the street art throughout the 2011 timeline, as carrying on that legacy of the printers? Was that parallel intentional in how you used image-making as a kind of resistance across generations?

Maria van Lieshout: I included the 2011 storyline partly because I wanted to show the two kids, Soli and Hanna as grown-ups, to show that war has such a profound effect on kids. War does not stay in the past, but if you’ve experienced war as a child, then you will carry that with you the rest of your life, and that’s why I felt strongly about including a 2011 storyline, but it was also a way to make the story feel more current for teenagers.

And we know that street artists are usually at the forefront of the resistance movement. I mean, they certainly are today. When we look at current events today we see that street art is really making us aware and is really sort of playing that role that maybe the printers and the artists and the sculptors had in the 1940s.

This is why I wanted to include the street artist character Koenji. And I felt that he could also be helpful to Annick in helping her decode some of the art because art is his language; he’s a good guide for her to help her navigate this world.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: Okay, last question. So, the orange indicates the 2011 timeline, the red is the 1943 timeline. Are there any other colors that I should be paying attention to? I felt like color functions almost like a second narrator, guiding emotion, memory, and even urgency within the stories. Both Annick and Emma are under pressures outside their control and also within their control.

Maria van Lieshout: So the story line in the past is mostly red, white, and black with aqua green. The reason I chose the red, white, and black colors is because those are the colors of Amsterdam. They signify the three disasters that Amsterdam overcame: white signifies the floods, black signifies the plague and red signifies the fires. Amsterdam has weathered so many storms in the past and yet it has overcome all these disasters. And it also overcame the Nazi terror during those years of the occupation. So that’s why those colors are meaningful to me.

I felt strongly about using a contrasting color in the present story line and orange was a logical choice just because orange is the Dutch national color.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: The symbolism is so rich and the spare use of color really makes that connection overt. And when you have Kirkus Reviews drawing connections between your novel and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, something that also immediately resonated with me as a reader of both texts, that signals a powerful contribution to the literature of resistance.

Maria van Lieshout: I’m such a fan. Marjane Satrapi has been such an inspiration to me. So to have some people draw that comparison is just the most amazing compliment.

Kim Tyo-Dickerson: And just as Persepolis has inspired so many readers and artists around the world, Song of a Blackbird is now doing the same. Your work is becoming part of that lineage, empowering a new generation to think critically, feel deeply, and maybe even pick up a pen – or a paintbrush – in response to the world around them. Thank you so much, Maria, for sharing your story, your process, and this remarkable book with us.

Note: AI was used to help organize and structure the Google Meet interview transcript for clarity and flow, but all of Maria van Lieshout’s words are entirely her own.

Author bio

Maria van Lieshout was born and raised near Amsterdam, where she spent many weekends in the Museum Quarter row house where her grandparents lived with her artist aunt and metalsmith uncle. Drawing while her aunt painted, and pecking stories on a typewriter while her uncle soldered metals inspired her love for drawing, creating and writing. After high school in Leiden, Maria studied Visual Communications at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and worked in design and innovation at Coca-Cola. In 2000, Maria became an illustrator full-time. She has illustrated/written several picture books. Song of a Blackbird is Maria’s first graphic novel. Please follow Maria on Instagram at @vanlieshoutstudio or visit www.vanlieshoutstudio.com for more information.

Further reading:

—Miller-Lachmann, Lyn. “#WorldKidLit Wednesday: Song of a Blackbird.” Global Literature in Libraries Initiative, 12 Mar. 2025.

—Van Lieshout, Maria. “Beeldcolumn #24 Maria van Lieshout” [“Image column #24 Maria van Lieshout”]. Illustratie Ambassade / Illustration Embassy, 2025.

—. “Maria van Lieshout Talks with Roger.” Interview by Roger Sutton. The Horn Book, 28 Feb. 2025.

⭐️5 Starred Reviews:

—Gall, Patrick. Review of Song of a Blackbird. The Horn Book Magazine, Mar.-Apr. 2025.

—Karp, Jesse. Review of Song of a Blackbird. Booklist, 1 Jan. 2025.

—Miserendino, Cat. Review of Song of a Blackbird. School Library Journal, 1 Nov. 2024.

—Review of Song of a Blackbird. Publisher’s Weekly, Nov. 2024.

—Review of Song of a Blackbird. Kirkus Reviews, 15 Nov. 2024.

Book information:

Song of a Blackbird, written and illustrated by Maria van Lieshout, published by First Second, 2025; ISBN: 9781250869821

Interest level: Booklist: Grades 8-12; Kirkus Reviews: Ages 12-adult; Publisher’s Weekly: Ages 14-up; School Library Journal: Gr 10-Up

You can buy a copy of Song of a Blackbird here or find it in a library here. (Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission.)

Kim Tyo-Dickerson is Head of Libraries and Upper School Librarian at the International School of Amsterdam. Kim has a Master of Library and Information Science from Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York. She also has a Master of Arts in English, with a concentration in 17th and 18th century British Literature, and a Bachelor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies with a Minor in Women’s Studies, from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. With over 20 years of experience in school libraries in North America, Europe, and Africa, Kim brings a global perspective to her work. Her practice is deeply informed by her Ethiopian American family and is grounded in social justice, with a focus on diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging. Kim was the guest editor for the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative’s #WorldKidLitMonth #DutchKidLit in September 2021. She also contributed to GLLI’s UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021, writing on Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender Equality. Kim’s languages are English, German, and Dutch, and she continues to explore multilingual intersections of language, literature, and identity. Connect with Kim on Bluesky and LinkedIn. Kim’s pronouns are she/her.

Katie Day is an international school teacher-librarian in Singapore and has been an American expatriate for almost 40 years (most of those in Asia). She is currently the chair of the 2025 GLLI Translated YA Book Prize and co-chair of the Neev Book Award in India, as well as heavily involved with the Singapore Red Dot Book Awards. Katie was the guest curator on the GLLI blog for the UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021 and guest co-curator for #IndiaKidLitMonth in September 2022.

3 thoughts on “#INTYALITMONTH: “Fight HATE. Make ART.” —Interview with Maria van Lieshout, Dutch American author.”