by Leah Janeczko

A wealthy lord summons an artist to his palace to paint murals in the three windowless rooms to which his young son is confined due to a life-threatening illness. The artist’s boundless generosity turns the simple commission into a years-long labor of love, and his paintings allow the boy to vicariously experience the life he cannot live in the real world.

This is the tale of Glowrushes by Italy’s foremost living children’s author, Roberto Piumini. Now in his seventies, he received the Rodari Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020 and was nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2020, 2022 and 2024. He is still writing and has authored hundreds of works for all ages, including novels, fairy tales, ballads, picture books, songs, sonnets, television programs and more, though only a handful of them have ever been published in English – something he and I set out to change, beginning with this book.

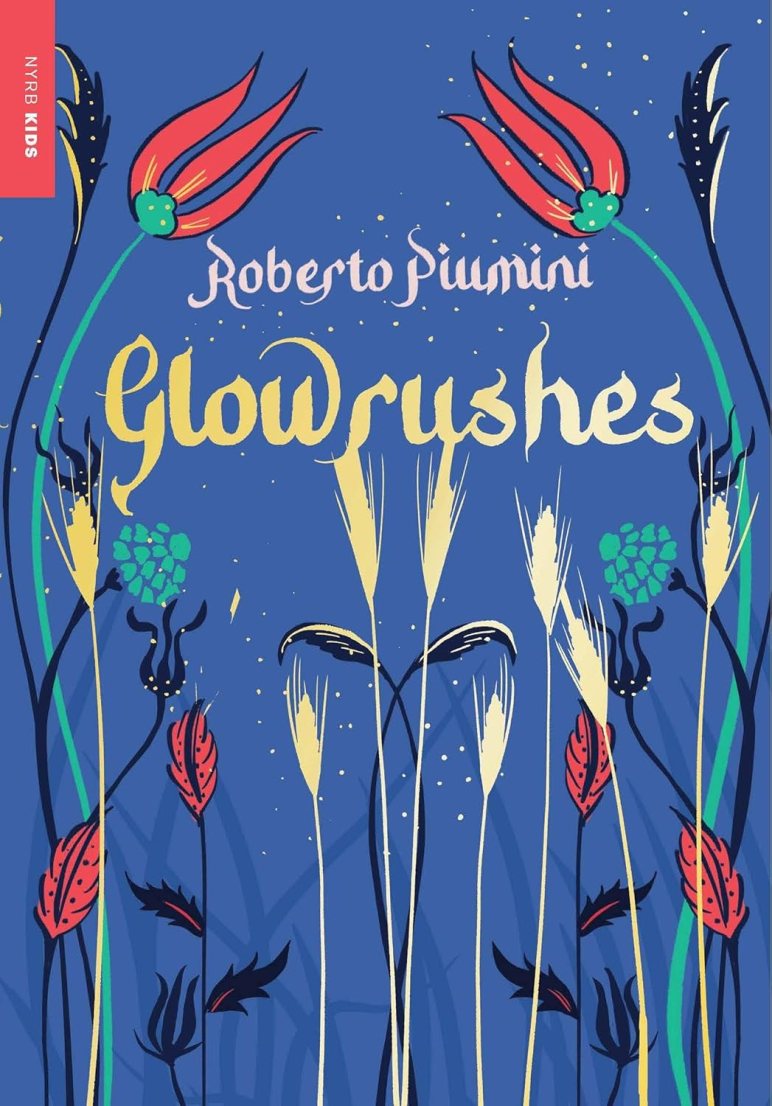

If Roberto Piumini is a national treasure in Italy, Glowrushes is his crown jewel. He wrote this novella in distant 1987, and since then it has been published both with and without illustrations, both as a children’s story and as short fiction for adults, and in translation in over a dozen languages. However, it took 35 long years for the first version in English to come out, and the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) has my heartfelt gratitude for giving me the opportunity to present my translation of it in 2021 through one of their brilliant, twice-annual rounds of Editor-Translator Pitch Sessions. Thanks to an eight-minute pitch on Zoom, I managed to find an excellent home for the book with Pushkin Press, who published it in the U.K. in December 2022. New York Review Books then released it in the U.S. in 2023. In both countries it was published without illustrations, allowing the scenes, characters and paintings conjured by the author’s magical storytelling to come to life in the reader’s mind using the palette of their own imagination.

Glowrushes has earned high praise from Philip Pullman (“I don’t think I have read anything like this before – a tale of life, death, love and beauty that by the storyteller’s art makes those things true, fresh, real and important. I hope this unforgettable story finds all the readers it deserves.”), Emily Drabble (“I cry, honestly, if I even think of this book. It’s truly a masterpiece and everyone has to read it. I’m just utterly gripped by the sparkling perfection of it.”), Jack Zipes (“A poetic novel … a profound contribution to literature in general.”) and Joseph Luzzi (“A masterpiece about a masterpiece”), while BookTrust President Michael Morpurgo chose it as his favorite children’s book of 2022.

(This rest of this article contains spoilers! Scroll down for book details, links and bios.)

What makes this book so distinctive, so unforgettable? Though its plot is straightforward and its style classic, Glowrushes is no ordinary story, because Roberto Piumini is no ordinary storyteller. Much of its uniqueness is found in three key aspects: its nested visual storytelling; its rich, poetic prose suitable for both children and adults; and, for the younger readership, its delicate theme of death.

Nested visual storytelling

While the outer story has minimal action points, the scenes depicted within the story make our experience far richer, vividly coming alive in the mind’s eye. The opening chapter describes the work of the artist, Sakumat, and prepares the reader for a visual journey:

As for the landscapes he imagined, who knows where he’d seen them. Not even he knew. Perhaps they didn’t exist anywhere in the world or in any human dream. Yet looking at them, they were like real lands that one could smell and touch. The more a person looked at them, the more their body would slip away through their eyes and journey, whole and alive, to colorful realms full of peace.

Though Glowrushes is character-driven, the development of bright, playful 11-year-old Madurer takes place through the stories depicted on the walls. In the first of the three rooms, he proposes that Sakumat paint simple landscapes and events the boy has seen in books or heard about in tales: hills, mountains, a shepherd and his flock. Then the two begin to make up their own stories, which are more detailed, the complex scene of a city under siege taking several months to paint.

In the second room Madurer not only “enters” the story by naming a character aboard a pirate ship after himself, but also suggests they alter their storytelling approach by painting over the ship again and again, changing it each time, making the story unfold before their eyes.

In the meadow in the third room Madurer becomes an artist in his own right by painting details, then boldly adding his own creation: wisps of glowrushes, an imaginary plant that lights up on starry nights. With this, despite his isolation from the actual outside world, Madurer has evolved into a participant in and co-creator of the world around him.

Chapter by chapter the reader is so deeply drawn into the imagery that it’s easily forgotten that the story takes place almost entirely within three windowless, isolated rooms. Rather than feeling trapped or claustrophobic, we find ourselves journeying through Sakumat’s “colorful realms full of peace”.

Poetic prose

The second aspect that makes our story so unique is that to Piumini the telling of a tale is as important as the tale itself, and given its eloquent, intelligent style, Glowrushes is more than a children’s story: it’s a work of children’s literature and also short fiction fitting for adult readers. It bridges these two age groups not only through its main characters – an adult and a child, giving each target someone with whom to identify – but also through Piumini’s straightforward yet distinctively poetic prose (or, as Joseph Luzzi describes it in his New York Times review, “sprezzatura”). One challenge I encountered during translation was finding just the right register in English for both children and adults, though many of the longer narrative passages consist primarily of visual descriptions, keeping it enjoyable and comprehensible to younger readers.

Days passed, and mountains were born. Not only the valley where Insubat and Mutkul lived, and the slopes on which the lame dog raced, barking after the herd, but many other valleys and peaks, huts and fences, goats that could be seen, snakes that couldn’t be seen, cliffsides and ponds with salamanders. It all slowly came to life, made of what Madurer and Sakumat knew of and imagined and wished for, sketching, changing, drawing, painting.

The movement of Sakumat’s hand was calm. It knew how to wait for the pictures—through words, laughter and memories—to be decided together.

The whiteness of the first wall disappeared, and in its place rose a mountainous part of the world, a space well balanced between the close and the infinite, between the deep and the towering. Each brushstroke had created a dimension, a direction and a truth.

Frequent dialogue and short chapters move the story along swiftly, keeping it accessible to children and appealing to adults who enjoy short fiction.

The theme of death

The third aspect that makes Glowrushes so unique, for younger readers, is that it broaches the delicate topic of death, this too through art. When Madurer’s health deteriorates and all hope of his recovery seems lost, Sakumat proposes they revisit their stories.

As he spoke, Sakumat played with the boy’s hands, like he often did. “Remember how we painted those things, Madurer?” he asked, clasping his fingers a little tighter. “How tiny the ship was at first? And how ‘unripe’ the meadow was?”

“Yes. We made them little by little. Bit by bit.”

“And remember something from even further back? That the world doesn’t have gaps and doesn’t stop?”

For a moment Madurer was quiet, weighing his smaller fingers in the painter’s larger ones. “You mean our landscapes can keep going?”

“They can keep going, yes. And changing. If we want them to.”

“Change how? By becoming more beautiful?”

“They’re already beautiful, Madurer. But we can move forward in the story, add the rest of their lives.”

And so, over the following months the shepherd grows old and gives away his flock, the siege upon the city ends, the pirate ship sails off for horizons unknown. Finally, Madurer watches as Sakumat brings winter to the once-lush meadow, slowly painting over it with somber tones and extinguishing, one by one, the radiant wisps of glowrushes. The boy peacefully accepts this change, having learned it is the natural course of life.

Nested stories, poetic prose and the delicate theme of death come together to make this a timeless and utterly unique tale. Roberto Piumini is a master storyteller, and Glowrushes is a masterpiece of children’s literature worthy of any home or school library.

Glowrushes

- by Roberto Piumini

- Translated from the Italian by Leah Janeczko

- Original title: Lo stralisco (1987)

- 128 pages

- For ages 9 to 12, and also adults

- New York Review Books (2023)

- ISBN: 978-1681377506

- Film adaptation rights available

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

Click here for Leah’s reading from Glowrushes on the Translators Aloud channel.

Reviews:

- The New York Times: Best Children’s Books of 2023

- The New York Times: Review by Joseph Luzzi

- Kirkus: Starred review

- The Times: Children’s Book of the Week

- Words Without Borders: World Kid Lit: The Best of 2022

This book has been translated thanks to a contribution awarded by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

Roberto Piumini is Italy’s foremost living author of children’s stories. His works are found in every Italian bookshop and school, and have been translated into many languages across the world. He received the Rodari Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020 and was nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2020, 2022 and 2024. In 2024 he was President of the Scientific Committee for IBBY’s 39th International Congress in Trieste. He is represented by Alice Fornasetti of the Grandi & Associati literary agency.

As Roberto Piumini’s trusted translator, Leah is working with him to find excellent homes for his books in English. She has prepared a wide variety of sample translations and synopses, which are available upon request. Read her article about his treasure trove of stories for children here.

Photo by Giovanna Scalfati

Leah Janeczko has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for readers of all ages for over 25 years. Originally from Chicago, she has lived in Milan for three decades. Her recent translations include At the Wolf’s Table (The Women at Hitler’s Table) by Campiello Prize winner Rosella Postorino, and Veronica Raimo’s Lost on Me, for which she and Veronica were longlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize. Leah also writes English song lyrics for Italian rock bands. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

“There are so many undiscovered jewels of Italian literature, and I’m eager to help their voices be heard in English.” —Leah Janeczko, guest curator of the GLLI’s Italian Lit Month

3 thoughts on “#ItalianLitMonth n.28: Glowrushes by Roberto Piumini: A Timeless Italian Masterpiece”