by Samantha Kokkat

Paro Anand, a celebrated member of India’s children’s literature community, writes short stories, novels, plays and poetry for children and young adults.

A fearless writer who has won accolades including the prestigious Sahitya Akademi Bal Sahitya Puraskar for her collection Wild Child and Other Stories, now published as Like Smoke, Paro is a pioneering writer who took difficult themes including terrorism and assault to children’s literature. Her book No Guns at My Son’s Funeral, translated into German and Spanish, was on the 2006 IBBY Honour List.

Paro headed the internationally recognized National Centre for Children’s Literature in India, took books to children in remote villages and set up libraries there. She also works extensively with children living in difficult circumstances, and has a podcast programme called Literature in Action.

In this interview, Paro champions diversity, and talks about the evolution in themes featured in children’s literature in India over the last four decades.

Q: You started writing for children in the 1980s, when mythological stories and books from the west dominated the Indian children’s literature market. Soon after, with the founding of a handful of independent publishing houses we started seeing a sea of change. Children’s books in English started to discuss unexplored themes and started featuring hitherto unseen characters. Experimentation with form became widespread too. What are the major shifts you’ve witnessed over the last 4 decades? Which are some of the books and authors that kindled this trail of change?

A: I fell into writing for children by default. I was a drama teacher who could not find any scripts that represented my students – contemporary, Indian young people. So I started to write my own, bouncing off ideas that children came up with in discussions and improvs. When I had a few performance ready scripts, I thought that the world of publishing would be kissing my feet (or at least fingers) for filling such an important void. I was mistaken. No publisher thought there was a market and my pleas, arguments and experiences fell on deaf ears. This was the early 1980’s. And my book of plays languished before coming out as my seventh publication. I talk about this because it is reflective of the ‘gatekeeper’ attitude towards books for the young. We feel we know what children need and often don’t examine ground realities closely enough. No wonder then that those who have access, prefer books from the West.

The big changes though have been in the subjects that children’s literature is now brave enough to follow. My book, No Guns at my Son’s Funeral, was the first to tackle, so directly a subject as difficult as terrorism. The title was less controversial than we had feared at first. This book was first published in 2003 and continues to be published 19 years later.

Since then dark subjects deftly told have been acceptable reading for younger readers. There has been wider character representation, Payal Dhar’s gay character in Slightly Burnt, Nandhika Nambi’s Unbroken with a strong, wilful character with severe special needs, Siddhartha Sarma’s historical novel set in WWII – The Grasshopper’s Run – are just a few of the many that dare to speak up and speak out what is in children’s hearts and minds.

Q: Publishing houses such as Children’s Book Trust and the National Book Trust were set up with a strong agenda of nation building, to make Indian children aware of their rich cultural heritage and to inculcate a scientific temper. In the late 1980s and 1990s, independent publishers such as Tara Books, Tulika Books, and Karadi Tales decided to move away from didactic literature and goal-oriented reading. These publishing houses worked with a goal too. But this time the aim was to portray a variety of Indian lives, to champion diversity, and to represent our cultural milieu in books for children. How far do you think we have succeeded? Which lives are represented in children’s books, which lives and regions are largely still ignored?

Inclusivity seems to have become a buzzword in children’s publishing in India, more so than in publishing for adults, why do you think that is so?

A: National Book Trust, under the editor, Mala Dayal, itself began to move away from being merely ‘high thinking’ books to more accessible ones. Look at Manjula Padmanabhan’s A Visit to the Market which is a wordless book that represents the real India that we see, feel and smell everyday.

HarperCollins came in with an imprint for children and they were publishing some excellent titles including Kalpana Swaminathan’s The True Adventures of Prince TeenTang that was a political story that also dealt with diversity and Subhadra Sen Gupta’s historical fiction that examined history belly side up. There were new perspectives and this was a very exciting time in children’s literature. Not much of it was selling, so children still didn’t really know Indian authors the way they do now, but it was a stirring start.

Starting here is key because in many ways we are still at the beginning, almost. While we are daring to be more irreverent, more daring, more fun, there are many subjects that we still find hard to tackle. One thing that boggles my mind is that adults find it less objectionable for children to read violence than love (and sex).

Many regions, many people’s stories are still untold. When I personally work with children in difficult circumstances, they almost always ask me to tell their stories because they want their stories shared. Not their mythology, but their actual lives.

Inclusivity is an important goal, along with creating empathy. We need to do this without moralising. But we are in a divisive world and inclusion of many kinds needs to be nurtured. It is, but we need to hunt for the unrepresented, the under-represented peoples and stories and bring light to them.

Q: You write about war, terrorism and even sexual violence. You have previously mentioned that children have never called your books inappropriate, but adults often do. Why do you think you find yourself drawn to topics that adults hesitate to discuss with children?

You considered changing the title of your bestselling novel No Guns at my Son’s Funeral because it sounded dreadful for a YA book, but decided to retain it the night before it went to print. Writing about heavy themes for a young audience requires nuance. What are the things you consider when you decide to feature heavy themes in your books?

A: I try to spend half my professional life working with young people, especially those in difficult and different circumstances and the other half writing for and about them. At the end of every session I always ask, “What do you want me to write next?” The real answers come away from the crowd, when one child follows me and asks for a private ear. Those are the real subjects they need – sexual diversity, inter faith relationships, domestic violence, sexual predation – even, once, masturbation. Knowing that these are the subjects that young people need, I venture into uncharted territory. This is why young people never object to my stories. Over the years, wondering why adults object to some themes, I have come to realise that it is a fear of the questions that may follow after the reading of a book. How would I answer this question becomes a genuine fear for a parent. And for a school it is the objections that parents would raise.

Yes, we changed the name of the book to Kashmir: The Other Side of Childhood. But I was so uncomfortable that I requested we change it back to the original which was, in fact, the starting point of the book. The title causes some unease amongst adults, but when I introduce several of my books to children before an interaction, then ask which one they want a reading from, it is always No Guns. I ask why and they say they’re drawn to the title.

The one taboo I impose upon myself is to leave a story on an upswing. Not necessarily a happy ending, but certainly, where there is hope.

Q: Representation is only one facet of diversity. We need diverse readers, diverse writers, and books in a variety of regional languages. Your work at the National Centre for Children’s Literature helped you realise that literature needs to reflect more and reach more. And we need diverse readers so that we can have diverse writers in the future. How can we rethink the ways in which books are being disseminated now? How do you take stories to communities who are struggling to survive? What value do books hold for them?

Books from the west dominated Indian children’s bookshelves a few decades ago. The fact that India’s children enjoy reading western books set in unfamiliar places, featuring unfamiliar characters speaks to our plurality in a sense. But it is important to see yourself represented in books too. What is the value of conscious representation in children’s literature? Would seeing themselves in books facilitate more reading in communities that rarely read and get to read?

A: Great questions but difficult ones that we have been trying to answer. I will concentrate on my work with the National Centre for Children’s Literature and my program Literature in Action.

Till the time I joined the NCCL, I had only really experienced a privileged urban group of children, barring a few. But through my work with this organisation, setting up rural libraries in the remotest of hamlets, taking books to where no books had even existed or seen, I realised the true value of them. The way children who had never held a book in their own hands took to them. The best way to describe it is through some examples:

- As we were wrapping up the book van late one evening and driving away, a woman was desperately banging on the side of the van waving a book. Her son had stolen money to buy a precious book. It was money that was to feed them for a week. The amount? Rs.10/-. Yes, we returned her money and gave the book to the child.

- In a thickly forested part of Rajasthan, a group of men dressed basically in leaves approached us and said they didn’t deal in money. Could we give them books in exchange for wild honey? We did. The honey was delicious.

- A tiny, pre reading child struggled out of his grandfather’s arms dashed into the van, grabbed the first book he could, clambered onto the family camel, made it stand with a commanding ‘huth huth,’ from there climbed onto a thorny keekar and flipped through the book. He couldn’t read, so he shouted down, “Daddu, kahani batao”. Daddu asked him to come down and show him the book, but the child wouldn’t, knowing full well that it would be taken away. Yes, once again, he got that book.

- In Kashmir, I told a story, the children enjoyed it, laughing in the right places, getting tense when they needed to. But at the end, they were uneasy, when I asked them to tell me what had happened, they asked if the story was true. It was a story about a bear that climbs onto the moon, so obviously it was not. But when I said this, there was a gasp of what can best be described as horror. “What?” I asked. Their reply, “If it’s not true then it is a lie and lies are haram.” When I protested that it was neither truth nor lies, but merely a story, they were blank. They actually didn’t know what a story was! I had never met a group of 8-year-olds who didn’t know what a story was. But when they got the idea, they just loved the books that I had brought.

- We set up Reader’s Clubs and gave sets of 50 books to start them off. One night, as we were leaving, a young girl came to me and said, “We were living in the darkness of ignorance, but we were happy because we had never seen the world of books. But now you’ve shown us this magical world. We will finish reading these books in no time. Now you cannot expect us to go back to that darkness, because now we know about them. What will you do to ensure that we continue to get books? This was a very difficult question with no easy answer. We couldn’t keep supplying free books and there were no bookstores or libraries within miles. So we hit upon the idea of a wall newspaper which would give the young a platform to express their own views, tell their own stories. It was hugely successful and they got a renewable resource of stories.

- A young girl asked me if a story I had told about domestic violence was true. I asked her what she thought and she said it most definitely was. “How can you be so sure?” I asked, and she looked at me and said, “Because it happens in my home.” This led to a very open discussion on domestic violence, how children feel when they witness it and what they can do about it.

There are instances aplenty, but suffice it to say that these stories have opened worlds for children and their stories have opened worlds for me.

Q: You have talked about your writing process in other interviews. You jump in without doing any homework, without much research﹘all of that comes along the way. Often, you and many other gifted writers like yourself write about communities that aren’t your own. You write about the other and have even brought out a book in that name! At the same time, it is also important to not lose track of authenticity as we champion diverse stories. The danger of essentialist narratives looms large. Do you put thought into how to remain true to your characters’ lived experience when you write stories? How can you achieve this when you write about difficult topics such as caste, class, gender, violence or poverty?

According to you, what is the value that own voice authors bring to children’s literature?

A: The best way I can describe this is that I like to write from the heart and gut and not from the head. I like the story to lead me by the nose and surprise me along the way with its twists and turns. My writing comes from personal experiences that may or may not be my own. So when I work with young people, I listen to their concerns, their issues, their language, the intonations, the interpersonal play of discussion. This is what informs much of my writing process. That is why, I think – and hope – it reads authentically. If I was to do a lot of research, for me personally, my narrative would be burdened by fact. So I like to write the story and then authenticate details such as what a particular people may actually be eating for a festival, how the younger ones would address their elders, etc. For me it is the story that is paramount. I am not writing a documentary, but a heartfelt story. I think that is why children enjoy reading my works.

The slogan – nothing about is without us – is one that I understand, but cannot always agree with. Look, how boring would it be if I could only write about an urban, Panjabi senior citizen woman and her immediate family! I believe in bringing light to stories way beyond my own. I don’t have had to have been a rape victim to write about sexual exploitation. Or a special need child to be writing about a little boy who falls hopelessly in love with the most sought after girl. Or be a tribal child to understand what it must be like to live in conflict. I have worked with many of the people I have written about. But not always needed to rely on that.

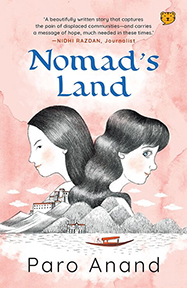

Only once, I was struggling. While writing Nomad’s Land, I wanted to be authentic to the Kashmiri Pandit story and also weave another narrative of displacement of a people. So I did a fair amount of research on the former. But not one other narrative was fitting all that I required. And so I made up people – their customs, their food, their names, their language. I drew threads from many stories of forced exodus, but invented my own.

The authorial voice, again, is not one that I consciously strive for. I hope, instead, to find the true voice of my character rather than my own. I actually very closely inhabit the skin of my lead protagonist.

Q: Diversity also includes variety in the kinds of books published. Poetry, drama, comics, riddles, travelogues and even nonsense verse were published in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Malayalam, Marathi and other languages as early as the 14th century, and all through the early to mid 1900s. It is only recently that this breadth reached children’s literature in English with the emergence of dedicated publishing houses. Still there are many gaps that need to be filled, it’s a long journey ahead. What are some of the glaring gaps that need to be addressed?

A: Really the subjects that we consider children’s literature. In many languages in our country, we still have a rather archaic idea of what constitutes CL. So we need to ‘grow up’ for the sake of our children who are exposed to a much wider world and need stories that help them figure out the world out there.

Q: You run Literature in Action, a programme that uses stories as a constructive and creative outlet. Could you tell us a little about the work that it does? How do diverse books add value to your programme?

A: I started the program when I discovered the importance of stories as doors that were opening people up to discussion. I realised that stories, fiction, provided a safe space to talk about what was concerning and even bothering them. They were talking about their issues, but through the eyes of a fictional character. So it was once removed and therefore safer.

I also realised that literature could be used in so many different ways to approach such an array of situations. From tribal children who were able to talk about their unique situation as children of poachers, to telling their stories to children who did not know what a story was at all, to the fact that children in a village were hungry for education. All of this could be covered through stories as discussion starters and also empower them to tell their stories and discover that their stories are worth listening to by outsiders.

I often go into a situation with one set of ideas of what I will do, but have to duck and weave according to what my group is actually demanding on ground. Whether it is very underprivileged children, or extremely well off urban children, they all need stories to firstly expand their own horizons and also to delve into their own in order to better understand themselves.

Samantha Kokkat is the Reading Community Manager at Neev Academy, Bangalore, and helps organize the Neev Literature Festival. Prior to this, she was part of an initiative which aimed to create a community of 1 billion young readers in India. She has written a children’s book published by MsMoochie Books, and holds a Master’s degree in English Studies.

September is #WorldKidLit month and this year the GLLI blog is exploring different aspects of #IndiaKidLit in the run-up to the 2022 Neev Literature Festival, a celebration of Indian children’s literature being held Sept 24 and 25 in Bangalore. At the Festival, the winners of the 2022 Neev Book Award, which aims to promote and encourage high-quality children’s literature from India, will be announced in 4 categories: Early Years, Emerging Readers, Junior Readers, and Young Adult.

- Karthika Gopalakrishnan is the Head of Reading at Neev Academy, Bangalore, and the Director of the Neev Literature Festival. In the past, she has worked as a children’s book writer, editor, and content curator at Multistory Learning which ran a reading program for schools across south India. Prior to this, Karthika was a full-time print journalist with two national dailies. Her Twitter handle is g_karthika.

- Katie Day is an international school teacher-librarian and one of the Jury Co-Chairs for the Neev Book Award. An American with a masters in children’s literature from the UK and a masters in library science from Australia, she has lived in Asia since 1997, including 15 years in Singapore, first at United World College of Southeast Asia and now at Tanglin Trust School. She has also lived and worked in Thailand, Vietnam, Hong Kong and the UK. Her Twitter handle is librarianedge.