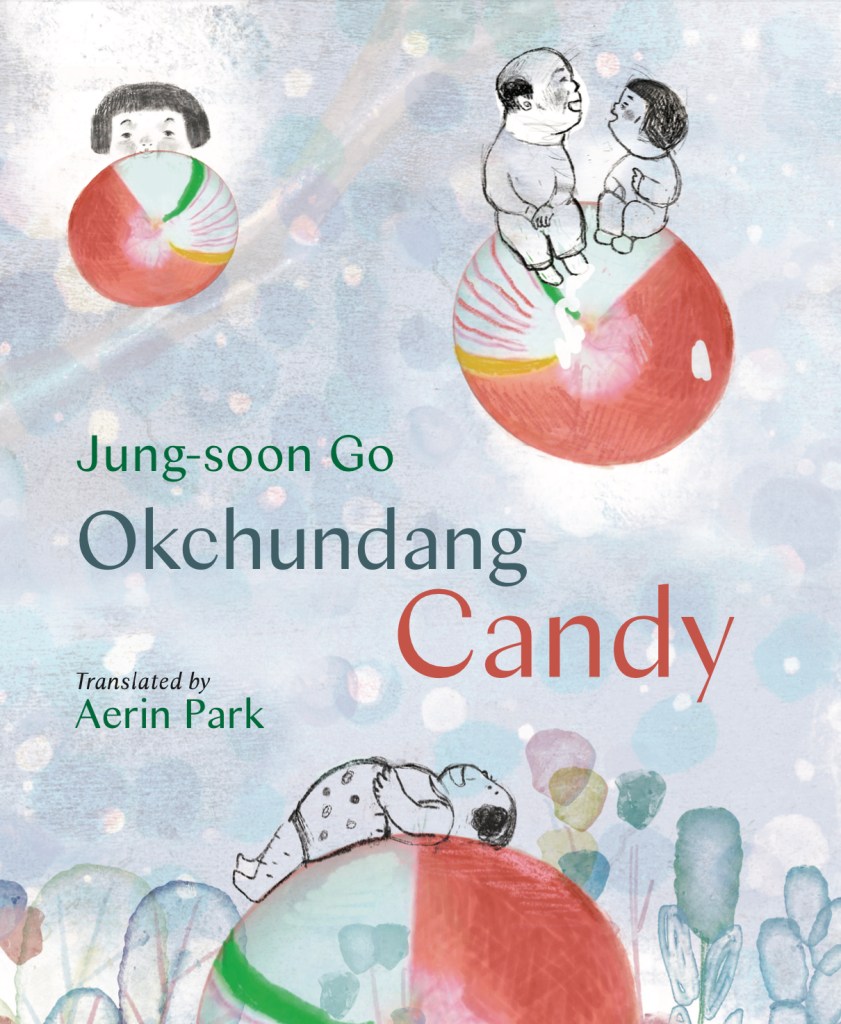

Translated from Korean by Aerin Park

Levine Querido, March 2025

“I still remember that house filled with summer lingering.”

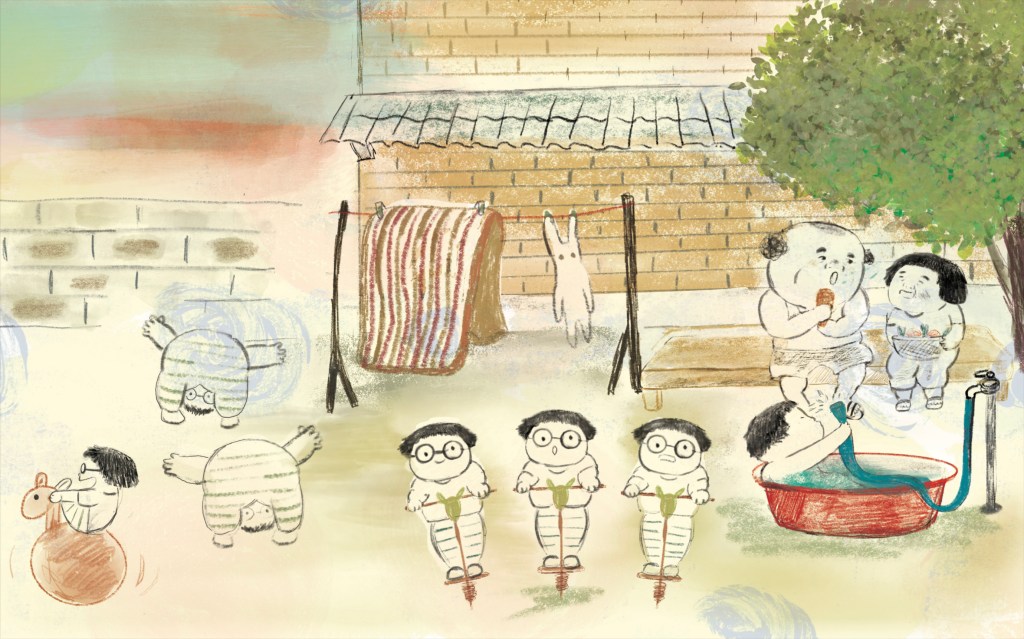

As the story opens, the narrator leads us back into the summers she spent with her grandparents, Mr. Go Jadong and Ms. Kim Soonim. Words rendered in crayon carry a handlettered quality, as if scribbled directly from the granddaughter’s childhood memories.

The pictures themselves, too, make a single pageturn travel great distances: One second, we chuckle as the kid, sandwiched between her grandparents—long passed out in sleep—stares at the ceiling, fretting over dyed fingernails tied too tightly with silk thread. The next second, the echoing TOOOOOOOOOT! of a train speeding through the dark gathers families from afar and marks the beginning of Jesa 제사: the traditional Korean ceremony honoring ancestors on the anniversary of their death.

Though life is pieced together through hard work, grandfather and grandmother have a way of finding peace and joy through the seasons, as vibrant colors bloom across the black-and-white sketches.

“Two squares for Pee, Three for Poop” is grandmother’s house rule to be frugal with toilet paper, but it turns into an opportunity for grandfather to crack jokes and teach his granddaughter a catchy tune. The “bar ladies,” shunned by many neighbors as bad influences, are instead welcomed into Mr. Go and Ms. Kim’s house with cheap rent—as Korean War orphans, they know what it’s like “not having a home to go back to,” so they try their best to carve out a place of warmth for others.

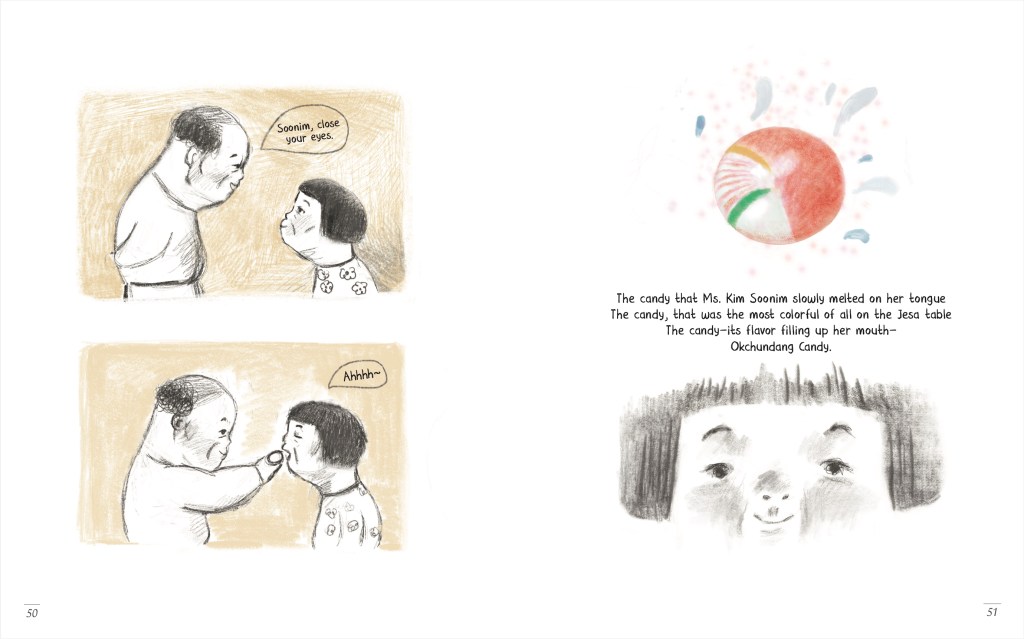

Yellowing pages evoke the nostalgia of leafing through an old family album. As the story moves into its second chapter “Thing That Can’t Stay Any Longer,” we may find that the many hues of the candy mirrors the many colors of life: joy threaded with grief, love inseparable from loss. However, even as grandfather’s body shrinks under the toll of final-stage lung cancer, his sunny spirit perseveres. He points to balsam flowers just beginning to sprout—

“Will this bloom next year too?”

—giving grandmother a small and steady hope to sustain the twenty years she would live alone after his death, waiting for grandfather to finally pick her up from “Bed 13 in Geumsan Nursing Home.”

“To you who believe in love,” reads the book’s dedication. Indeed, Okchundang Candy is to be cherished by little ones and grown-up folks alike. In Ms. Kim and Mr. Go’s everyday moments, their love lived patiently—in hardship and laughter, side by side—also carry the memory of Korean history across an entire era. And throughout, we’ll find Jung-soon Go’s restrained and all the more poetic prose, translated by Aerin Park into an English that leaves our heart in wonders long after the final page:

“I touch the stories in my picture books gently as if smoothing out clothes.”

When I look back at the book’s cover and see the okchundang candies—once so small they could be cradled in grandfather’s palm as he gently placed them into grandmother’s mouth, now in flight and big enough to carry the two elders, looking each other in the eyes with a lifetime of love—I am sure that as long as people keep returning to okchundang candy every Jesa day to remember their ancestors, the life of Mr. Go Jadong and Ms. Kim Soonim, as well as the little girl’s memories at her grandparents’ house, will be kept forever sweet “with summer lingering.”

About the Author

Born in Seoul, Jung-soon Go spent her childhood around the Sorae port, Incheon. She lived in a room at the back of a game arcade. She draws the things that she cannot describe with words and writes about other things that are hard to express in a drawing. Go’s works include Guard Up, A Wire Elephant, We’re Here, at the Zoo, The Most Wonderful Day, Like a Roughneck Princess, Cotton Pants of Mr. Cotton, Super Cats, Mumu’s Moon Swing, Jeombogi, Kkamjeongi and a collection of prose, I’m Fine. For Okchundang Candy, she won Special Prize in the 2023 Korea Picture Book Awards.

About the Translator

Aerin Park, born and raised in South Korea, believes that language is a bridge to people’s stories, culture, and history. She is passionate about integrating these elements into her work—both translation and Korean language teaching. When not working, you will find Aerin sharing Korean history with her three children, making kimchi from garden veggies, and shoveling the Minnesota snow.

About the Reviewer

Hongyu Jasmine Zhu, from Chengdu, is a Brown University student, Editor-at-Large for China at Asymptote, and a 2024 SCBWI Scholarship recipient. Her translation of Zhou Jianxin’s Little Squirrel and Old Banyan is forthcoming in 2026, and her writings appear in World Kid Lit, Words Without Borders, PEN Transmissions, and elsewhere. Jasmine is busy collecting picture books from around the world, to open a reading room where no one is too young or too old to play.

looks fantastic!

LikeLike