Written by Melissa Cooper

A flurry of kindergarteners zoom past on tricycles, sticks clenched between their teeth, fully in character as Nezuko, the demon from the wildly popular manga Demon Slayer. This series took Japan by storm, captivating everyone from toddlers to teens. Despite its violent story – beginning with the brutal slaughter of the Kamado family by a demon – Demon Slayer became a cultural phenomenon. Its 2020 film Demon Slayer: Mugen Train became Japan’s highest-grossing movie ever and then swept across North America in 2021. Librarians everywhere are now scrambling to find manga titles and, more importantly, to determine what’s appropriate for their students and communities.

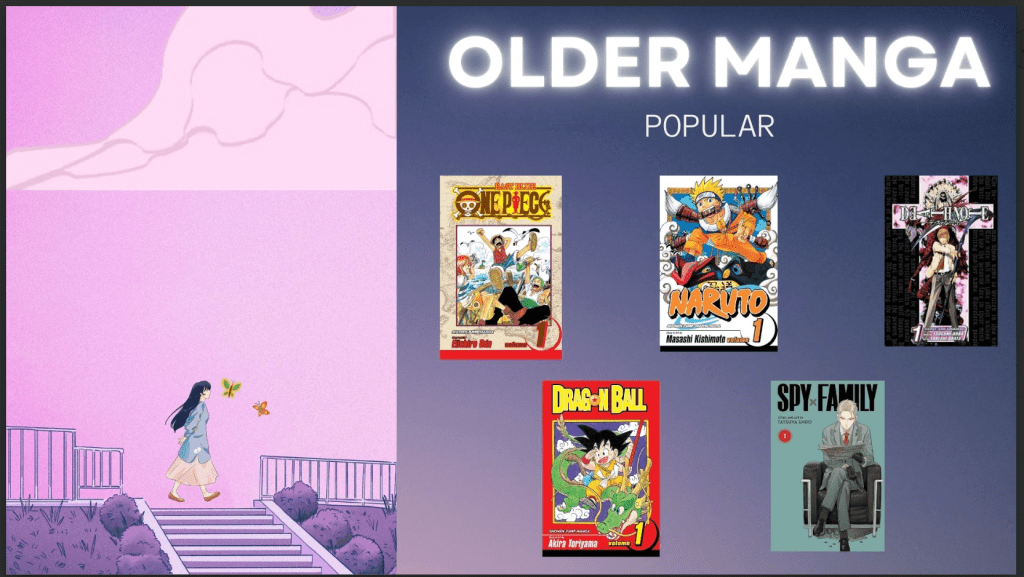

During the pandemic in Japan, my son and I became wannabe otaku-pop culture nerds collecting figures, cosplaying, and devouring manga and anime. We enjoyed fan favorites like One Piece, Dragon Ball, Assassination Classroom, Spy x Family, Naruto, and Death Note (the last two even appear on IB-DP recommended reading lists). What struck me was how what’s acceptable in my international school library in Japan wouldn’t fly in my primary school library in Singapore.

Manga can be controversial – whether Japanese manga, Korean manhwa, or Chinese manhua – and many librarians and parents wrestle with the same questions: How can teens access manga safely, both digitally and physically? What content is appropriate in different cultural contexts?

When I first started, I spent hours browsing physical manga at Kinokuniya in Osaka’s Umeda station. Now in Hong Kong, my access to a wide range of translated manga is more limited. For anyone new to manga, or you’re looking to explore whether something is appropriate for your library, I would recommend looking at different titles featured on Webtoon which is a legal platform and is recommended for ages 13 and up.

There’s plenty of manga and manhwa available, but the Chinese manhua is still an emerging market and finding physical copies of manhua can be especially challenging.

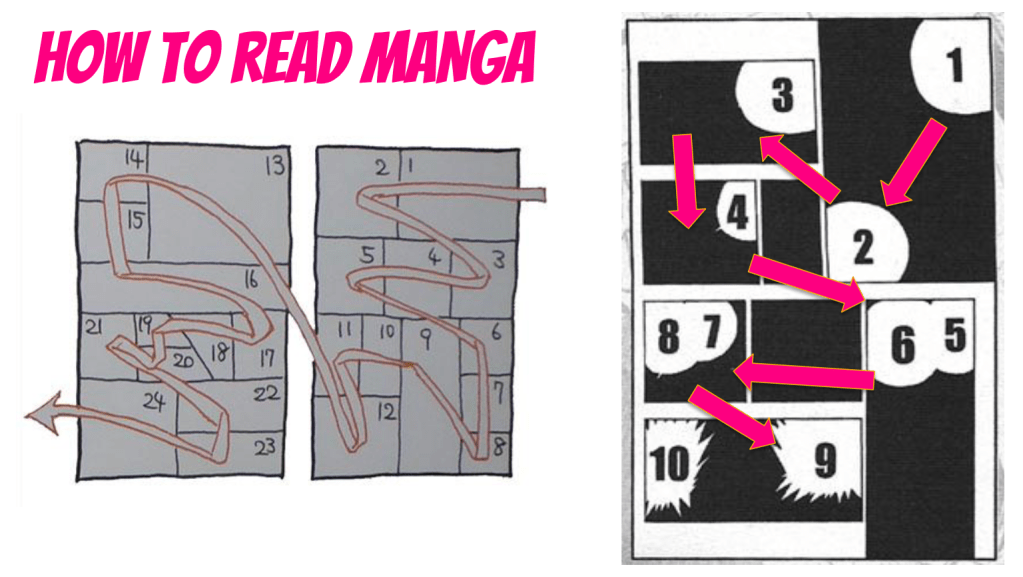

An interesting aspect of the world of manga is that most of them, even translated works, are written in the Japanese format, so you are reading from back to front and right to left. My students (and son) are a bit snobby about this and do not want to read a ‘westernized’ version. Apparently, it has been quite costly to ‘translate’ manga and more can be found here in this 2023 NY Times article.

Violence and sexual themes are woven deeply into manga culture. My son once asked why Nami from One Piece had breasts shaped like bowling balls, which sparked a valuable conversation about the objectification of women. This is exactly why librarians should preview manga carefully before adding it to collections. Even guides like the Japanese Shonen Manga Guide, which rates content levels, reflect standards that may differ greatly from what’s acceptable elsewhere. I’ve found the VIZ website especially helpful – it aims to help educators and parents navigate appropriateness based on their context.

There are subtle differences between manga, manhwa, and manhua when it comes to violence and sexual content. Korean manhwa tends to be tamer, focusing on romance, societal issues, and fantasy, often with K-pop connections. Chinese manhua has worked hard to avoid gore and explicit content, often featuring historical or wholesome romantic stories. Currently, I have only one manhua in my collection due to availability and interest, but I’m eager to explore more, maybe a trip to Shenzhen’s book stores is in order!

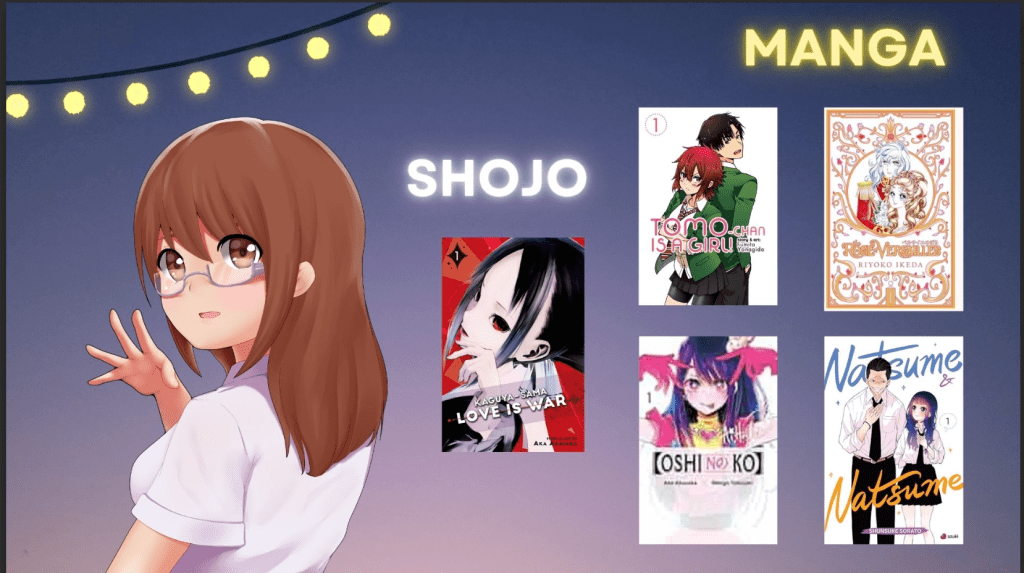

One caveat: many manga genres reflect inherent sexism that is deeply rooted in Japanese culture. When building your collection, it helps to know some key terms, especially when exploring GameRant or Comic Book Review and both these sources have impressive recent lists.

Shōnen manga targets adolescent boys and young men, while Shōjo manga is for teenage girls and young women. Other popular genres include Seinen (for young adults), Supokon (sports manga), and Kyooiku (educational manga). In my experience, teens enjoy both Shōnen and Shōjo regardless of gender, so don’t worry too much about strict targeting.

Manga and its variations are fantastic additions to any library collection and consistently boost circulation. They engage students, spark conversations, and open windows into diverse cultures and storytelling styles. Just remember to consider your community’s values and preview content carefully. Happy reading!

Other resources

- Manga in Libraries blog – run by Jillian Rudes

- Manga in the Library 101 – Jillian’s 2023 YALSA 1-hour webinar on manga, free on YouTube

- Anime New Network

- Shonen Manga Guide

Mel Cooper is a teacher librarian and tech coach at Renaissance College in Hong Kong. Not new to international schools, she has worked in Japan, Singapore, Cambodia, Hungary, and China. One of the joys of being an international librarian is collaborating with fellow librarians to read and curate books for awards, as well as planning and hosting professional development. This Canadian loves all literacies and thoroughly enjoys the challenge of hunting down an elusive title for a middle schooler or figuring out the ethical use of AI in a research project. When her nose isn’t in a book, she can be found hiking or planning her next adventure!

Katie Day is an international school teacher-librarian in Singapore and has been an American expatriate for almost 40 years (most of those in Asia). She is currently the chair of the 2025 GLLI Translated YA Book Prize and co-chair of the Neev Book Award in India, as well as heavily involved with the Singapore Red Dot Book Awards. Katie was the guest curator on the GLLI blog for the UN #SDGLitMonth in March 2021 and guest co-curator for #IndiaKidLitMonth in September 2022.

One thought on “#INTYALITMONTH: Manga, Manhwa, and Manhua”