by Stiliana Milkova Rousseva

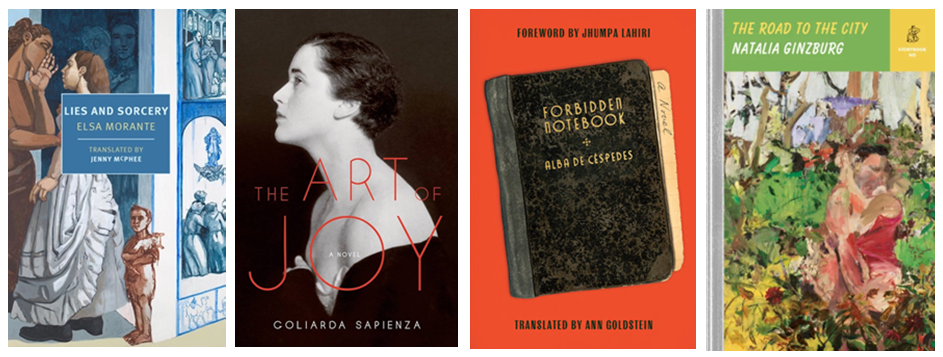

In the wake of Elena Ferrante’s global popularity, it has become somewhat of a trend for mainstream publications to “introduce” or “discover” other Italian women writers in English translation. This trend arises partly from readers’ curiosity and thirst for new voices and partly from critics’ and publishers’ intent to capitalize on the momentum – and demand – created by Ferrante’s gripping Neapolitan novels. The works of influential Italian writers Elsa Morante (Lies and Sorcery), Goliarda Sapienza (The Art of Joy and Meeting in Positano), Lalla Romano (A Silence Shared), Alba de Céspedes (Forbidden Notebook), Anna Maria Ortese (Neapolitan Chronicles), and Natalia Ginzburg (most recently, The Road to the City) have arrived on the Anglophone literary scene to an enthusiastic reception.

Each of these Italian authors merits extended discussion to situate her within the context of both Italian and global literature and to illuminate her contributions to a powerful and growing canon of women’s writing worldwide. I focus on Natalia Ginzburg, whose writing seems particularly relevant to our current reality marked by personal and collective traumatic experiences.

Natalia Ginzburg (1916-1991) was an Italian writer, translator, playwright, and essayist who worked for a time at the paramount publishing house Einaudi, co-founded by her husband Leone Ginzburg. She had friendships and exchanges with many of the most important authors of the twentieth century, including Giorgio Bassani, Italo Calvino, Alba de Céspedes, Primo Levi, Elsa Morante, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Cesare Pavese. In other words, she was at the center of Italy’s flourishing post-war cultural industry, and in 1963 her novel Lessico famigliare won the most prestigious Italian prize for literature, the Premio Strega.

Her life was difficult, but she sublimated hardship into superb writing. Ginzburg grew up in Turin, the fifth child of the renowned Jewish professor Giuseppe Levi and his Catholic wife Lidia Tanzi. She lived through the horrors of fascist Italy and the racial laws. In 1940 she accompanied her husband, the anti-fascist political activist Leone Ginzburg, on his internal exile. And in 1944, shortly after she followed him to Rome with their three children, Leone was tortured and murdered in a Roman prison. They had been married for six years.

Beginning in the late 1940s, she established herself as one of the most revered 20th-century writers, crafting a lucid, dispassionate voice that narrates war, exile, abandonment, disillusionment, resignation, apathy, and death through the intimate—and often oblique—perspectives of marginalized figures and individual family histories. She weaves autobiography, fiction, and non-fiction into new literary forms that defy the borders of genre. Today, more than thirty years after her death, her writing is more relevant than ever, as the geopolitics of war and violence and the hypervisibility of suffering, death, and disease are reshaping both literature and our relationship with reality. With her characteristic economy of expression, she constructs a world of objects and domestic spaces, of moral dilemmas and human behaviors, of quotidian routines and ordinary lives which in its totality possesses a universal, timeless resonance.

Unlike Italian authors recently “discovered” by Anglophone publishers (such as Lalla Romano and Goliarda Sapienza), Ginzburg has had a noticeable presence in the Anglophone world since the last century. While the first English translation of her most famous work, Lessico famigliare, followed the French and German ones, there are now three English translations, a rarity for any modern Italian work: Family Sayings (by D.M. Low, 1967), The Things We Used to Say (by Judith Woolf, 1997), and Family Lexicon (by Jenny McPhee, 2017). Her collected stories, novellas, novels, plays, and numerous essays are also available for English readers, some of them in more than one translation. Rachel Cusk, Sally Rooney, and Colm Tóibín have provided introductions for recent editions of her works, which include Minna Zallman Proctor’s translation of Happiness, As Such (2019), Gini Alhadeff’s new translation of The Road to the City (2023), the reprinted editions of The Dry Heart (2019), Valentino and Sagittarius (2020), Family and Borghesia (2021), and Voices in the Evening (2021). And, significantly, New York Review Books has commissioned the (re)translation of Ginzburg’s four volumes of essays.

Despite this increased visibility of Ginzburg’s translated works and renewed engagement with her writing, there has been very little literary criticism on her. Anglophone reviewers tend to either focus on her biography as a lens to analyze her writing or else read her works outside any Italian-specific context, sometimes even ignoring their status as translations. And by now there are more stand-alone scholarly works in English on Elena Ferrante than on Natalia Ginzburg. A recent volume of essays, Natalia Ginzburg’s Global Legacies (Palgrave, 2024), addresses this gap in literary scholarship. Bringing together Anglophone and Italian scholarship from around the world, the volume examines topics generated by Ginzburg’s texts and ranging from world literature and world making to female bodies, voices, and gazes to identity, topography, and literary form.

Intended for both scholars and general readers, Natalia Ginzburg’s Global Legacies provides an accessible yet robust framework for reading Ginzburg in the 21st century. This framework can serve as the foundation for future reviewers’ informed engagement and open new lines of critical inquiry. And to circle back to the opening of this essay, the recent and ongoing (re)translations of many more Italian and Italophone women authors provide English-language readers with a chance to situate Ginzburg’s crucial contributions to world literature in Italian and transnational contexts.

Natalia Ginzburg’s Global Legacies

- Edited by Stiliana Milkova Rousseva and Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski

- 287 pages

- Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan (2024)

- ISBN: 3031499069

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

Stiliana Milkova Rousseva is a Bulgarian-born writer, translator, and professor of Comparative Literature at Oberlin College (USA). She is the author of Storia delle prime volte (Voland, 2022) and the co-author of Fuori scena (Acquario, 2023). Her translations from Italian include works by Italo Calvino, Antonio Tabucchi, Alessandro Baricco, Dario Voltolini, Adriana Cavarero, and Anita Raja. Her scholarly publications include Elena Ferrante as World Literature (Bloomsbury, 2021) and Natalia Ginzburg’s Global Legacies (Palgrave, 2024). She edits the online journal Reading in Translation.

“A native speaker of Bulgarian who lives in an English-speaking country, I found my creative voice by reading and translating Italian literature.” —Stiliana Milkova Rousseva

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

One thought on “#ItalianLitMonth n.34: Natalia Ginzburg and Italian Women Writers in Translation”