This article first appeared on the ALSC Blog on April 16, 2024. Reposted with permission.

Not long ago, I asked a group of grade six English learners to do a “source language scavenger hunt,” finding middle grade and YA novels in the school library and recording the language in which each was written. I also had them note the author’s name and, if applicable, the translator’s.

This “hunt” had several goals:

- I hoped it would get the students comfortable ferreting out works of fiction in their library. I also wanted them to consider language among the many markers of authorial identity, since they were performing a diversity audit of their independent reading.

- I wanted them to see their bilingualism as a superpower. As users of both English and Languages Other Than English, they might one day translate novels themselves, using their cultural savvy and linguistic artistry to bring works they admire to new audiences.

- I wanted them to see authors in their languages named and “meet” some translator role models.

But it turned out that both the authors’ languages and the translators’ names were elusive, requiring a second hunt through the books. Some authors’ languages had to be guessed at based on the home countries in their bio paragraphs and checked online. Translators’ names could often only be seen in small print on the title or copyright pages.

The books we were accessing had been published shortly before the movement for translators on the cover, and before the criteria for the ALSC Batchelder Award—the Newbery for translated children’s books—changed to require publishers to name translators.

But the books, movement, and criteria change point to a norm that still prevails in English-language children’s publishing: de facto Anglocentrism, or English supremacy. Books published in English for children and teens are largely written in English, to the point that we scarcely notice this. At the same time, books authored in Languages Other Than English, particularly in non-western languages, are seldom available in translation.

In 2023, less than 4 percent of new children’s titles published or distributed in the U.S. that were received by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) at the University of Wisconsin were translations, according to my tabulations of their data, which I requested. In some recent years, this figure has approached 5 percent but never reached it. In the market I translate from, Japan’s, even 15 percent translations is considered low for the children’s book industry; it is not unusual for developed nations’ figures to exceed 30 percent translations.

Translations are a rich source of diversity. Anton Hur, who led the Korean-to-English translation team for the bestselling BTS memoir Beyond the Story, describes languages as “psychic neighborhoods.” The UN refers to each language as a “cultural and intellectual heritage”—and estimates that every two weeks, a human language disappears.

If we think about it, don’t we want young readers to visit many linguistic-psychic neighborhoods? And wouldn’t we like to support authors writing in Languages Other Than English, keeping them vibrant?

If so, we can urge children’s publishers to publish non-anglophone authors in translation, which adds to the authors’ income. In so doing, publishers can name authors’ languages, so that young readers of English can gauge source language diversity in their reading—and find books born in languages personal to them.

It also helps when publishers name translators, so that multilingual children can see an avenue for using their gifts. One day, this will mean more translations!

Naming translators on/in books has long been considered best practice by PEN America and the Authors Guild. Edith Grossman, the legendary translator of Gabriel García Márquez and Miguel de Cervantes, argued that literary translation is an interpretive art, like that of an actor performing a play. When I translate middle grade novels by Sachiko Kashiwaba, I make constant artistic decisions to elicit the same emotional experience, moment by moment, that she produced in me using Japanese.

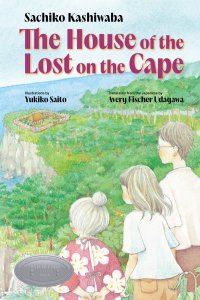

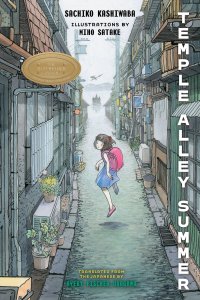

So I appreciate that Yonder: Restless Books for Young Readers names both Kashiwaba’s language and me, after her, on book covers. Unfortunately, this combination is rare.

Philip Nel has argued that obscuring the race of books’ characters by whitewashing covers reflects, and perpetuates, white supremacy. Similarly, I would submit that omitting the author’s language and/or translator’s name—usually to hide that a book is a translation—amounts to English-washing that perpetuates English supremacy.

Many in publishing have worked to overcome unproven hang-ups around how Others can or cannot be acknowledged, if we are to sell books.

I hope we can get less hung up on Languages Other Than English in children’s literature. Let’s embrace translations today while naming authors’ languages and translators.

We can all do so, even if we don’t design covers, by routinely naming source languages and translators when we review, teach, sell and share books.

Avery Fischer Udagawa’s translations include the 2022 Batchelder Award-winning novel Temple Alley Summer and the 2024 Batchelder Honor book The House of the Lost on the Cape, both authored in Japanese by Sachiko Kashiwaba. Avery works in international education north of Bangkok.

I’d like to comment on three points that arise:

As a retired teacher-librarian, I can vouch for the fact that it is hard to source books in translation for a primary library, but the ones that I had were terrific for discussions about the wider world. And yes, naming the translator is a recent phenomenon, none of my childhood books in translation that I still have, did it.

As a litblogger who reviews adult books, I always name the translator, prominently in the title of the post. I tag them too. It’s common sense to recognise the work that has been done to bring me a text that I can’t read in the original language. (I can read in French and Indonesian and speak three more, but there’s a whole lot more languages than that!)

I don’t necessarily think that there’s a problem with the supremacy of English, it is, after all, the international language which brings us all together — and in my classes throughout my career I was teaching children for whom English was a second language and stories was part of my armoury for teaching them to be confident and fluent in it. But I think it’s also important to name the language and ‘country’ of First Nations authors. In my classroom, I had a large map of Australia, marked up not in the usual states and territories but with the traditional boundaries and languages of the First Nations people as they were before First Contact. Whenever I read a story by a First Nations author, we would find the ‘country’ and the language on the map, so that by the time we’d finished the unit of work, the students understood that the contemporary lines on the map of Australia are just one way of mapping it and — as well as a rich tapestry of languages such as we find in any multicultural country — Australia also has First Nations languages to celebrate.

LikeLike

Oops #Typo! “stories *were* part of my armoury, (not *was*).

LikeLike