The Baška tablet, found in the 19th century on Krk. Source: Wikipedia.

Last September I was in the Balkans, specifically in Montenegro, looking for traces of the Glagolitic script created (probably) about 1200 years ago, (probably) a few hundred miles south of here, (quite likely not) by the brothers Cyril and Methodius who (probably) didn’t create Cyrillic as well.

What we can be more certain about is that it was created specifically to write Old Church Slavonic, the language that would be used by the Orthodox Church as it made its way north and east through the Slavic-speaking lands, ultimately even to Russia. Hence its name, from the Slavic word glagoljica (pronounced “glagolitse”), meaning “writing.”

And what we can say with some certainty is that it was gradually supplanted by Cyrillic, its user base shrinking to a handful of priests on the dramatic, rocky Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic, and when the last of them died in the late twentieth century, it was generally thought dead.

It survived in stone, engraved into the walls of certain churches throughout the region, and that’s where I stop the history lesson and start with the things I have seen over the past few days and what they might mean.

So back in September I was staying in Kotor, a fortified port in an extensive inlet into the Eastern shore of the Adriatic, so sturdy and strategically placed it was a southern outpost of the Venetian empire for some 377 years. This was an interlude, though, in a series of invasions and assaults that had begun with the Illyrians, Romans, Byzantines, Serbians, Hungarians and Bosnians and would subsequently be continued by the Austro-Hungarians, the French, the Austro-Hungarians again, the Italians and the Germans. And finally, of course, there was the brutal civil war that broke Yugoslavia apart at the end of the twentieth century.

In Kotor the trained eye can still see Venetian architectural styles, just as it can see Austro-Hungarian influence just two villages up the coast, and Ottoman traces immediately inland.

But what my eye saw, everywhere and again, in every shape and for virtually every purpose, was rock.

Kotor, Montenegro. Photo by the author.

In Kotor, as in much of the coast, stone churches and cathedrals and monasteries line the shore, but then, astonishingly, rise up the almost vertical 3,000-foot limestone cliffs behind the town in parallel with Kotor’s defensive wall, a wall in places twenty feet thick, zig-zagging upwards, an incomprehensible labor against an incomprehensible assault.

“The only thing breaking through there,” observed my daughter Zoe when I sent her a photo, “is time.”

Everything here is made of stone. The palaces are made of stone. The narrow steps running up the narrow alleys are stone. The old city’s main street, generally barely more than the width of a cart, is made of stone, with twin runnels that act as both cart tracks and a storm-water runoff system. It’s a region with few mineral resources, almost no grazing or arable land—its only assets are water, giving access to the Adriatic and the world, and the perdurable rock, and it is impossible to look at this region and not see the uncompromising rocks, from which the partisans fired at the Nazis and among which they disappeared again, as something more than an asset, more like a spiritual underpinning.

And yes, I’m yoking together the rock and the Glagolitic script. I had not thought of doing so until we took a day trip inland to the Bosnian border and I had a Montenegrin guide—actually, no surprise here, by birth a Serb who had fled the bombing of Belgrade in 1999 with his parents and was now as ardent a Montenegrin as anyone—who could tell me Balkan history in all its heroic and desperate fierceness.

It was a strange, dual narrative. One thread told of a constant series of invasions by greater powers, of massacres, of mountain sections that had never been conquered by any of the invaders because frankly there was nothing there worth conquering but a source of savage pride anyway by those who lived there, of a single victory over the Ottomans, 5,000 men against 50,000, but even that being a kind of defeat as the site has now been bought up by a corrupt minister and turned into a vast restaurant-hotel complex, part of a continuing insult to the only country in the world with a commitment to ecology in its constitution, honored more in the breach than in the observance.

“We could be such a wonderful country,” he said. “Such a wonderful country.”

The other thread concerned the Orthodox Church, and rock. Down in the bay was a tiny island church called Our Lady of the Rocks, where according to legend two brothers had been shipwrecked but managed to survive by clinging to a single rock. They vowed that once a year, on July 22nd, they and their descendants would come back and throw rocks—that being their only materials, their only currency, around the savior rock and so it was, and over the years and decades it became (and still is) an annual ceremony.

Eventually they formed an island, and built a church to Our Lady, the merciful, the deliverer.

Farther inland we came across a gorge so deep it had its own weather system, the site of a village flooded to make the largest artificial lake in the country, a blessing of its own in that it finally gave the tiny new country of Montenegro its principal export: hydroelectricity.

But in the village, as in just about all villages, was a monastery, a place so revered that when the dam was being planned the villagers took the monastery apart, stone by stone, carried it above the projected waterline, and reassembled it.

We pulled over by the guardrail of a bridge spanning this gorge, and I started to jot down thoughts that were coming to me from the air, from the water, from the rocks above and below.

“What are you writing?” he asked.

I told him that I had this sense of the Glagolitic script, so ornate that every letter looks like an icon encrusted with precious stones, a script bound to lose out in the secular long run against a simpler script like Cyrillic, as being something central to this region, something half-buried but still alive.

“Of course,” said my guide, with that Slavic isn’t-it-obvious shrug. “The Church is what has protected our culture, our traditions.” Our continuity in the face of never-ending assault.

And the Church was founded on rock. “Peter,” said punning Jesus, giving his disciple Simon a new name: petros, the Greek for “rock.” “You are the rock on which I build my church.”

This all left me thinking three things, all new, one quite unexpected.

We are used to thinking of the US as the place where old enemies slowly forget their enmity, softened and healed and merged by goodwill and prosperity. For the first time I decided that people need their own history even if it is one of regular invasion and defeat. That it doesn’t help to forget the Armenian genocide, the Drogheda massacre, the pogroms, the lynchings. These are the rocky and unpromising landscape we have survived, and that survival is such an achievement that we take fierce and bitter satisfaction even in the mountain regions nobody conquered because they were not worth the effort.

The second is that script is history in many, many ways. Even if we can’t read it anymore, or even if it is used only for sacred ceremonies or for tourist junk, it is ours. It has been on that long rocky journey with us, and in many cases, we have carved it in stone to make sure time does not break through.

A people is never free, said King Njoya of the Bamum kingdom of Cameroon while his people were ruled by the Germans, unless they have their own history written in their own script, an astonishing insight. So, he created a script for his people and used it to write their history. Theirs and theirs. Done and done.

Fact is, just up the coast in Croatia they have begun using Glagolitic again, here and there, in massive letter-sculptures, on certain town signs, as a branding device for goods and services. Scholars are starting to write very serious papers about the commodification of the Glagolitic script in tourist trinkets, the dark power of the script in the hands of Croatian nationalists.

I wonder if there isn’t just an element of oversimplification in both points of view. I can’t help thinking of it as Glagolitic emerging from the rocks like the partisans at the end of World War II, its hour come back at last.

A Historical Outline of Literary Croatian/The Glagolitic Heritage of Croatian Culture

by Branko; Zagar Franolic

Publisher : Erasmus Publisher Ltd (January 1, 2008)

Language : English

ISBN-10 : 953613280X

ISBN-13 : 978-9536132805

Also, some more esoteric interpretations or uses of Glagolitic, such as:

Slavic Life-Giving Glagolitic

by Elena Kryuchkova (Author), Olga Kryuchkova (Author)

ASIN : B09W2W9HXR

Publisher : Independently published (March 20, 2022)

Language : English

Paperback : 119 pages

ISBN-13 : 979-8436622729

Item Weight : 6.1 ounces

Dimensions : 6 x 0.27 x 9 inches

…and the more scholarly….

Art and Mysticism: Interfaces in the Medieval and Modern Periods (Contemporary Theological Explorations in Mysticism)

by Louise Nelstrop (Editor), Helen Appleton (Editor)

ASIN : B07DP4ZSK6

Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (June 12, 2018)

Publication date : June 12, 2018

Language : English

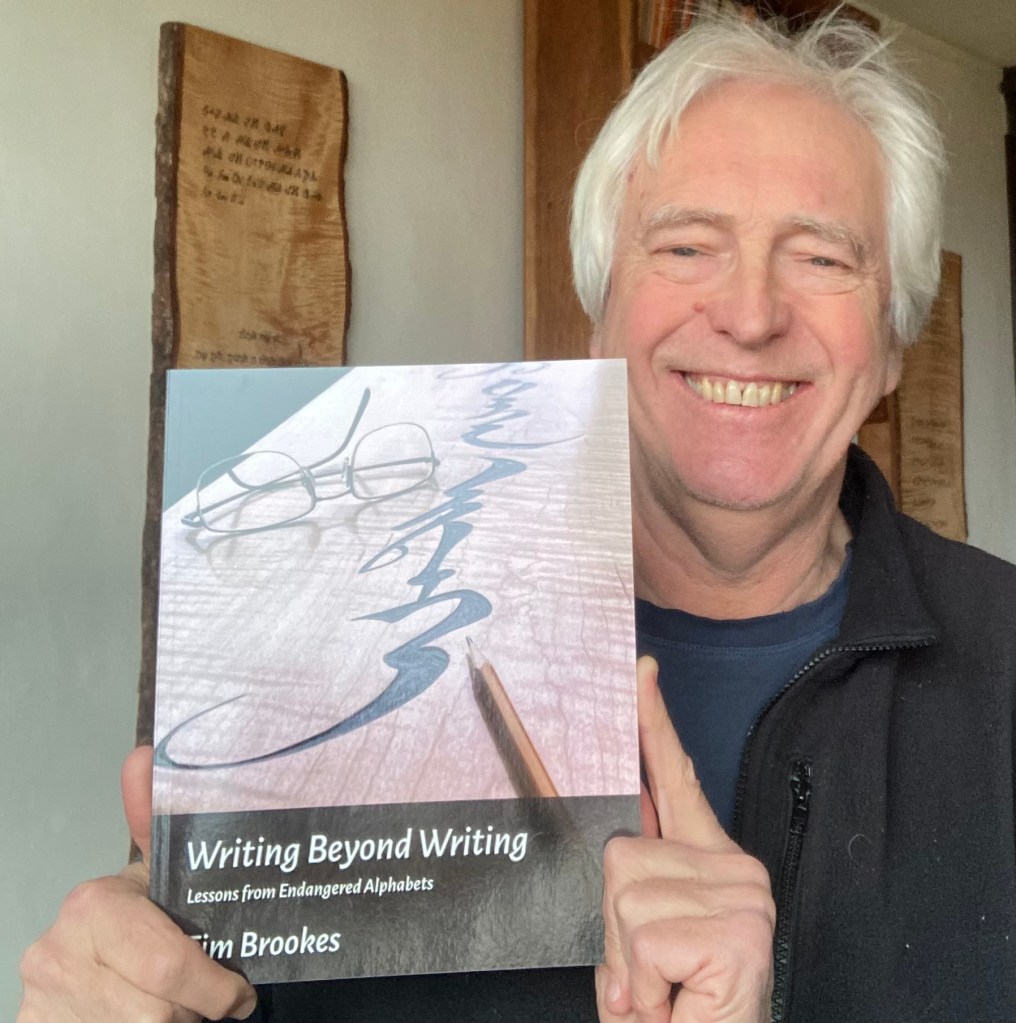

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.