“Refusing the Minefields: a Humanist Confronts Inhumanity,” Reflections on Rachmil Bryks’s May God Avenge Their Blood: a Holocaust Memoir Triptych.

by Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

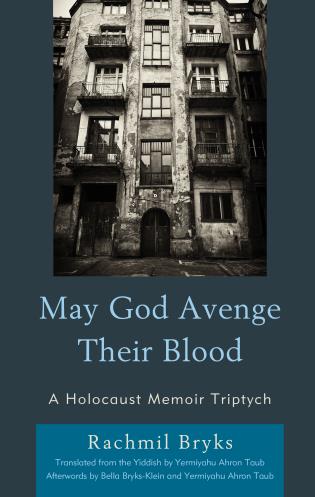

May God Avenge Their Blood: a Holocaust Memoir Triptych

By Rachmil Bryks

Translated by Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

Afterwords by Belly Bryks Klein and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

Lexington Books, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, 2020. Series: Lexington Studies in Jewish Literature.

ISBN: 9781793621023 (hardback); 9781793621030 (ebook); 9781793621047 (paperback)

I am delighted that new readers can now appreciate the autobiographical works of Rachmil Bryks, a gifted and versatile Yiddish writer whose life and creativity were cut short by his premature death, an artist who remained steadfast, despite immense affliction, in his commitment to his art—and his folk. An artist who deserves to be more widely known and celebrated. And I am deeply grateful to Bryks’s extraordinary daughter, Bella Bryks Klein, for her tireless advocacy on behalf of her father’s work and the Yiddish language and culture that was so vital to him as well as for her support of my translation project.

Rachmil Bryks was a gifted writer in the humanist tradition. His work is characterized by a flair for lively description and narration, deep empathy for his characters, and a carefully calibrated attention to moral complexity. Even in the darkest of circumstances, he is interested in the humanity of all those he is observing, including perpetrators of evil. Bryks is particularly adept at capturing the dialogue of a wide spectrum of protagonists—Jews in the shtetl of every political and religious persuasion, passengers on trains, pedestrians on the street, and concentration camp inmates and their guards, among many others. May God Avenge Their Blood is, as the subtitle suggests, a memoir in triptych, its three parts uniting to tell the story of its author and the world around him.

Part One: Those Who Didn’t Survive

Those Who Didn’t Survive, the first work in the triptych, is an elegiac, deeply affecting memoir of Bryks’ shtetl Skarżysko-Kamienna, Poland. As its title demonstrates, the book eschews a self-focused approach, centering instead on the author’s maternal great-uncle Mendl Feldman, a wealthy Hasid with influence in the Jewish and Polish spheres. Indeed, the book’s entire first passage is devoted to a physical description of Reb Mendl and a highly detailed description of his clothing. The reader gets to feel the weight, solemnity, and color vibrating beneath this extended sartorial meditation. Taken as a whole, this first book is part character study/ies, part reportage, part collection of folkways and vignettes. The protagonists are colorfully described, and the scenarios are expertly drawn. Bryks presents the shtetl’s folk traditions and an extended cast of characters, while always deftly returning the thread to Reb Mendl. In the process, a vivid collective portrait of an annihilated Jewish community emerges. What initially appears to be a hagiographic approach on the part of the author to the text’s larger-than-life, almost mythic main character slowly moves in quite a different direction altogether. It is certainly tempting for the reader to view Reb Mendl’s life and end as a metaphor for the fate of Polish Jewry itself.

In this work, Bryks’ narrative approach is unconventional—there are no chapter breaks or readily apparent chronology. The book is more a panorama chock full of anecdotes, characters, customs, and details than a traditional memoir with a linear narrative drive. We meet individuals from nearly every sector and political stripe of society—Jew and Pole, rich and poor and in between, men and women, religious and secular, and Zionist and socialist. We meet Bryks’s maternal grandmother Libe, the sister of Reb Mendl, who, like her brother, gave generously and unhesitatingly to the poor; Yidl Kogen, known as Yidele with the fidele, who wasn’t given a Jewish name because he was uncircumcised (this was permitted by the rabbi because six previous sons had died because of circumcision); Reb Mendl’s daughter, Ester Rivke, who elopes with a non-Hasid; the ne’er-do-well Shmuel-Yoyne with his dreams of striking it rich; and so many others. We learn how tea was cooked, how weddings were celebrated, how prayer services were conducted, what kind of pastries were given at ritual circumcision ceremonies. Largely assuming the observational position of anthropologist, Bryks makes rich use of his powers of description and talents at capturing authentic dialogue and compelling narration. Only occasionally does he insert himself into events of the book.

Part Two: The Fugitives

In The Fugitives, in contrast, Bryks emerges fully as a character. Here, he describes his experiences from the breakout of war in September 1939 until the establishment of the Łódź Ghetto in May 1940. He portrays the confusion and uncertainty in the population as the German army advances into Poland. In Łódź, the terror inflicted by the air raid sirens, the race to shelter, the search for food as supplies dwindle are captured to great effect. Mass media plays a pivotal role in the narrative, as Bryks highlights the interplay between actors shaping the political events of world history and everyday people. Civilians seek to comprehend the increasingly incomprehensible developments they hear about on Polish radio, but the propaganda only foments chaos and panic. The effects of propaganda are visible throughout The Fugitives and From Agony to Life in both the dialogue spoken and actions taken by numerous individuals Bryks encountered in the war years.

Some of the most powerful scenes in The Fugitives are of the citizens of Łódź on the move—crowding the highways, with their valuables piled up, desperate to escape the bombings. The German net ensnares Bryks, and he experiences the horrors of captivity at the hands of the Nazis even before his internment in the Łódź Ghetto. Bryks depicts the depth of anti-Semitism in the Polish population, but also the moments of kindness shown him and others.

In contrast to some Holocaust memoirs that move quickly over the events at the beginning of the war or begin with internment in the ghettoes, The Fugitives dramatically, indeed kinetically, delineates the hopes, uncertainty, and mounting desperation of the early stages of the war before the Nazis tightened their chokehold over Poland and mastered the machinery of industrial-scale genocide. I am not aware of any other memoir that portrays this period with such detail and power.

Part 3: From Agony to Life

The final section of the triptych charts Bryks’ deportation to, experiences in, and liberation from Auschwitz and other internment camps. His depiction of the camp experience is relentless. The effects of starvation, privation, and brutality on the body and soul, the tedium in the camps, and the terror in being shunted from one camp to another are rendered with stark clarity. Bryks probes the dark recesses of human agency, including the sexual abuse of minors, sparing no one, least of all himself, from his unflinching eye. He finds moments of connection and courage amidst the conditions of extremity. Bryks’s belief in art as a life force and his commitment to his own calling as an artist is a leitmotif in this and indeed in all three of the works translated here.

***

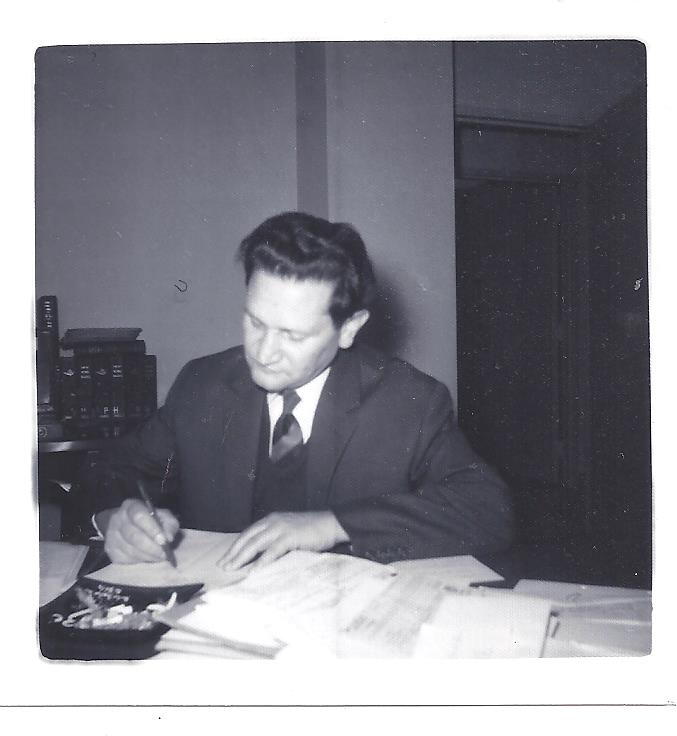

Born and raised in a Hasidic milieu in Skarżysko-Kamienna, Poland, in 1912, Rachmil Bryks was a prolific and highly acclaimed Yiddish poet and writer. The third of eight children, he received a traditional and secular education. His book of poems Young Green May (Yung grin may) appeared in 1939. At the outbreak of World War II, Bryks was in the industrial city of Łódź working as a hat maker and housepainter. Much of his family perished in the Holocaust. His brother Simkhe Elozer (born 1916) served in the Polish army against the Nazis and helped liberate Poland.

In June 1946, a Polish nationalist shot and killed Simkhe and his bride Sonya Milshteyn two days before their wedding. Of his immediate family, only Rachmil, his brother Yosef (b. 1924), and sister Libe (Lucia) survived the war and its aftermath. Bryks was interned in the Łódź Ghetto from 1940-1944, where he continued to write and participate in literary events. In August 1944, Bryks was transferred to Auschwitz and later to Wattenstadt, Ravensbruck, and Wöbbelin.

The American Army liberated Bryks on May 2, 1945, and the Red Cross brought him to Stockholm, Sweden, for recuperations. There, he met Hinde Irene Wolf, herself a Holocaust survivor, and the two eventually married. They had two daughters, Myriam Serla and Bella Svea. In March 1949, the family emigrated from Sweden to the United States. From the end of the war until his death, Bryks dedicated his creative life to writing about the Holocaust. He was the author of seven Yiddish-language books and contributed extensively to the Yiddish press. Rachmil Bryks died in New York City in 1974.

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is a poet and writer in English and Yiddish and a translator of Yiddish literature. He is the author of two books of fiction, Beloved Comrades: a Novel in Stories (2020) and Prodigal Children in the House of G-d: Stories (2018), and six volumes of poetry, including A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems (2017). Taub’s most recent translations from the Yiddish are Dineh: an Autobiographical Novel by Ida Maze (White Goat Press, 2022) and Blessed Hands: Stories by Frume Halpern (Frayed Edge Press, 2023). Please visit his website.

LINKS:

“Rachmil Bryks’ Holocaust Memoir Triptych,” a podcast conversation with Lisa Newman on The Schmooze,August 13, 2020. https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/the-shmooze/270-rachmil-bryks-holocaust-memoir-triptych

Rachmil Bryks. “A Gas Nightmare.” Yiddish Book Center: Trans. Yermiyahu Ahron Taub. https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/yiddish-translation/gas-nightmare

Rachmil Bryks. “At Home with Mordecai Gebirtig.” In geveb, April 2020: Trans. Yermiyahu Ahron Taub. https://ingeveb.org/texts-and-translations/at-home-with-mordecai-gebirtig.

Brian Horowitz. “Book Review: Rachmil Bryks, May God Avenge Their Blood: A Holocaust Memoir Triptych.” Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe, December 2020. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2233&context=ree

Mikhail Krutikov. “From Hasidic Shtetl to Nazi Camp,” Forward, July 30, 2020. https://forward.com/forverts-in-english/451789/from-hasidic-shtetl-to-nazi-camp/

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub reads an excerpt from May God Avenge Their Blood: a Holocaust Memoir Triptych. Translators Aloud Series, YouTube, February 7, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hrOfE-7KZKQ

The translator gratefully acknowledges the Yiddish Book Center for a 2018 Yiddish Book Center Translation Fellowship from which this book arose.

#YiddishLitMonth is curated by Madeleine Cohen. Mindl is academic director of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, MA, where she directs the Yiddish translation fellowship and is translation editor of the Center’s online translation series. Mindl has a PhD in comparative literature from UC Berkeley. She is a visiting lecturer in Jewish Studies at Mount Holyoke College and president of the board of directors of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies.

I have read quite a few Holocaust memoirs, and in recent years I have reviewed them on my blog to coincide with Holocaust Memorial Day. The relentlessness of this one sounds more difficult to read than others I have come across, but I always remind myself, that if those who perished and those who survived had no choice but to bear it, I can at least make myself bear reading about it.

LikeLike

Well said, Lisa.

LikeLike