The most famous and probably most important writer born in Bulgaria is Elias Canetti. The Nobel Prize Winner was born 1905 in Ruse at the Danube, at that time an important trading center and the most modern town in Bulgaria. Although Canetti was neither by ethnicity, nor by nationality, nor by language a Bulgarian author – his native language was Ladino and he wrote in German -, his early childhood in “Rustchuk” (Canetti always used the old Ottoman name of the town) was a very important influence for him and his life, and that is particularly true for the multi-cultural and multi-linguistic atmosphere in Rustchuk at that time, which made it a small metropolis, where you could hear every day easily seven or eight different languages spoken on the street.

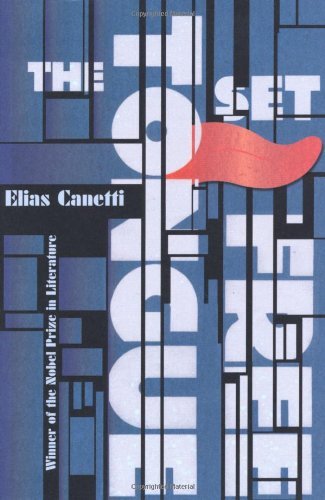

A little bit more about Canetti’s life and family background in Rustchuk you can find here. But in any case I strongly recommend you to read his autobiography, one of the great intellectual coming-of-age stories of anyone who has lived through the 20th Century. In the first volume, “The Tongue Set Free” (Die gerettete Zunge, 1979; newest English edition: Granta Books 2011, translation Joachim Neugroschel), Canetti describes in detail how he and his understanding of the world was shaped in Rustchuk.

In a radio emission of “Radio Free Europe”, Canetti said later about his birthplace:

“I will hardly succeed in giving an idea of the colorfulness of these early years in Rustchuk, of his passions and horrors. Everything I experienced later had already happened in Rustschuk.”

Nevertheless, the descriptions of his childhood in Rustchuk in the book are evocative and frequently unforgettable, such as the following short paragraph:

“In this kitchen yard was often a servant who chopped wood, and the one I remember best was my friend, the sad Armenian, who sang songs while chopping wood, which I did not understand, but which tore my heart. When I asked Mother why he was so sad, she said that bad people had wanted to kill all the Armenians in Stambol, that he had lost all his family there … – When he put down the axe, he smiled at me again, and I waited for his smile as he did for me, the first refugee in my life. “

Canetti never returned to his birthplace in his later life. He didn’t want to confront the Rustschuk of his imagination and memory with the place Ruse had become later. That must have been a mechanism of protection and defense against the reality of modern Ruse that would have probably destroyed much of the charm and magic Rustchuk had occupied in Canetti’s very vivid childhood memory.

Thomas Hübner

Elias Canetti (b. 1905, Ruse/Bulgaria—d. 1994, Zürich) was a German-language novelist, memoirist, playwright and essayist whose works explore the emotions of crowds, the psychopathology of power, and the position of the individual at odds with the society around him. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1981, the Georg Büchner Prize, the Franz Kafka Prize, the Great Austrian State Prize for Literature and many others. Canetti was a descendant of Sephardic Jews. He wrote in German, while his native language was Ladino (Judeo-Spanish). He settled at the age of six in England. After his father’s death in 1913, he moved with his mother to Vienna. Educated in Zürich, Frankfurt, and Vienna, Canetti received a doctorate in chemistry at the University of Vienna in 1929. Canetti’s interest in crowds crystallized after he witnessed street rioting over inflation in Frankfurt in 1923 and the burning by an angry mob of the Vienna Palace of Justice in 1927. A planned multi-novel saga of the disorder he saw around him was reduced to Die Blendung (1935; Auto-da-Fé, or The Tower of Babel), the story of a scholar’s degradation and destruction in the grotesque underworld of a city. In 1938 Canetti immigrated to England, devoting his time to research on mass psychology and the allure of fascism. His major work, Masse und Macht (1960; Crowds and Power), is an outgrowth of that interest, which is also evident in Canetti’s three plays: Hochzeit (1932; The Wedding), Komödie der Eitelkeit (1950; Comedy of Vanity), and Die Befristeten (1964; The Numbered). The first two were first performed in Braunschweig, in 1965 and the third in Oxford, in 1956. They were published as Dramen in 1964. In addition to the novel and plays, Canetti also published Die Provinz des Menschen: Aufzeichnungen 1942–1972 (1973; The Human Province), Das Geheimherz der Uhr: Aufzeichnungen 1973–1985 (1987; The Secret Heart of the Clock), and Die Fliegenpein (1992; The Agony of Flies), all excerpts from his notebooks; and Der Ohrenzeuge: Fünfzig Charaktere (1974; Earwitness: Fifty Characters), a book of character sketches. Canetti published three volumes of autobiography: Die gerettete Zunge (1977; The Tongue Set Free), Die Fackel im Ohr (1980; The Torch in My Ear), and Das Augenspiel (1985; The Play of the Eyes). A fourth volume, written in the early 1990s, was published posthumously as Party im Blitz (2003; Party in the Blitz). Canetti published also a travel book Die Stimmen von Marrakesch (1958; The Voices of Marrakesh, 1968), and the essay Der andere Prozess (1969; Kafka’s other trial, 1974). During the last twenty years of his life, Canetti lived mainly in Zürich. He is buried beside James Joyce.

Joachim Neugroschel (b. 1938, Vienna – d. 2011, New York) was a well-known literary translator from French, German, Italian, Russian, and Yiddish. He also published poetry and was a poetry magazine founder. His father was Yiddish poet Mendel (Max) Neugroschel. The family immigrated to Rio de Janeiro in 1939, and later to New York (1941). Neugroschel graduated from Columbia University in 1958 with a degree in English and Comparative Literature. He then moved to Paris and later to Berlin. He returned to New York six years later and became a literary translator. Neugroschel translated more than 200 books of numerous authors, including Sholem Alejchem, Bergelson, Chekhov, Dumas, Hesse, Kafka, Thomas Mann, Moliere, Maupassant, Proust, Albert Schweitzer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Ernst Jünger, Elfriede Jelinek and Tahar Ben Jelloun. His Yiddish translations of The Dybbuk by S. Ansky, and God of Vengeance by Shalom Asch, were produced on stage and reached wide audience. He was the winner of three PEN Translation Awards, the 1994 French-American Translation Prize, and the Guggenheim Fellowship in German Literature (1998). In 1996 he was also made a Chevalier Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Thomas Hübner is a German-born economist and development consultant with a life-long passion for books. He lives in Chisinau/Moldova and Sofia/Bulgaria. He is also the co-founder of Rhizome Publishing in Sofia, and translates poetry, mainly from Bulgarian to German (most recently Vladislav Hristov, Germanii, Rhizome 2017). He is blogging at Mytwostotinki on books and anything else that interests him.

Photo credits: Dutch National Archives; Broadway Play Publishing; Cornelia Awear

This blog post is part of #BulgarianLiteratureMonth.