Our next post is a conversation between educators about a specialized book club in Portland, Maine, USA. They discuss book club title selection, favorite international mysteries, and the problems with “translation” in a beloved series. Enjoy! – Rebecca Starr

My name is Lynn Lawrence-Brown, and I am a Taiwanese-American teacher librarian working at Shrewsbury International School in Hong Kong. I grew up in Maine, but have spent about three-quarters of my life in Greater China. Aside from four years during COVID, I come back to Maine every summer, and one of my annual highlights is to participate in the International Mystery Book Club.

The club was formed over 14 years ago by Dr. Phyllis Rogers, a former UCLA, University of Santa Cruz, Amherst College and Colby College professor. Specialising in anthropology and American studies, Phyllis was one of my favourite professors at Colby; we’ve been in touch for over 30 years.

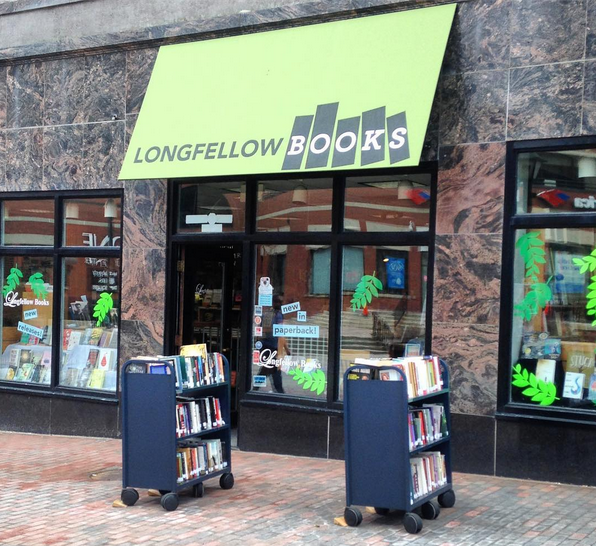

I love that her book club supports Longfellow Books in Portland because the members order their books through that independent book store. At its height, the book club had over 40 members and it still has a loyal following with some original members and new members ranging from age 23 to 85.

This summer, Phyllis and I reconnected on our annual sojourn up the coast of Maine. I had a chance to interview her about the origins of the International Mystery Book Club, how she keeps it going, and what women mystery writers in translation she recommends.

Lynn: How did the International Mystery Book Club come to be?

Phyllis: When I moved to Portland, I used to bake cookies for Longfellow Books’ book readings and book clubs, and during these sessions I would also help staff the desk. People would ask me what I liked to read and I would tell them mysteries and cookbooks. They asked if I would start a book club, but I joked and said I would only start one if I got to pick all of the books – for this, I’ve been nicknamed “The Benevolent Dictator.”

The next thing I knew, the former owner, Stuart Gersen, said people were signing up and asked what I wanted to call it and when it would start. I decided I’d call it the International Mystery Book Club and would only have mysteries set outside of the U.S. because I wanted members to learn about different cultures and countries around the world. I also decided to link my passion for cooking and have a meal and dessert from the country the book is set in.

Before COVID, we would meet once a month in the back room of Longfellow Books, but now we meet online, aside from one month in the summer when we meet at Karen Gersen’s house.

Lynn: So how do you pick your books?

Phyllis: I read reviews and I take recommendations, but I skim read over 40 books per year to narrow it down to 12. I also try to have December be “Read the book and see the movie month” where we read a mystery and compare it to the movie version.

Lynn: Are most of the books in translation? How do you narrow down each year’s selection?

Phyllis: It is a mix of those written in English and those translated from the original language to English. The criteria for selection are:

- Stories are outside of the U.S., aside from Native American mysteries;

- No mysteries involving the murder of children;

- No overly violent stories;

- Mysteries need to give an authentic flavor or sense of the country;

- The title needs to have a paperback version to make it more affordable for members.

Lynn: So why are Native American mysteries an exception? Can you elaborate on what you mean by ‘authentic flavor or sense of the country’?

Phyllis: Despite Native Americans being in North America longer than the rest of the populations, these cultures are little understood and as foreign to some people as the other countries we are reading about in the book club. Native authors also tend to use their own language in their stories. So despite some of these titles being set in the U.S. or Canada, I think Native American populations should be included in the mix.

Perhaps it’s my anthropology studies training, but I really hope through the book club and reading each of the mysteries that members are learning about different time periods, cultures and countries.

Lynn: I definitely think all members love the book club because of what they learn about different cultures and countries. I also love how you often give a brief commentary on the historical and political backdrop of the country the books are set in. It helps in widening and giving more depth of understanding to the stories.

What are the different types of mysteries, and do you try to include the different sub-genres?

Phyllis: There are lots of different types of mysteries: cozies, procedurals, detective, capers, and more, but the international mysteries don’t necessarily follow the U.S. book publishing trends. My focus is just finding good mysteries and mysteries that have been translated well.

Lynn: Tell us more about the mysteries in translation. Do you think these mysteries may lose some of the local flavor in the translation?

Phyllis: Sure, translation is an art and skill just as important as the writing, and a bad translation would mean the books don’t make it on our list. The second mystery we ever read, when the book club started, was Camilla Läckberg’s The Ice Princess (2003; English edition, 2004). We slogged through that terrible translation. It was so idiomatically translated from Swedish but didn’t always make sense in English. It wasn’t until 70 books later in 2011 that we re-visited Läckberg by reading her second book, The Preacher (2004; English edition, 2009), which had the same translator, Steven T. Murray, and yet that was a much better book.

Translation is a collaboration between the writer and the translator, but it is also a partnership or even a friendship. Sometimes it takes years of working together to develop the trust needed to create an understanding that allows for the original language and its nuances to be successfully conveyed in another language. It also takes a while for a reader of an unsuccessful translation to be willing to return to that author and translator. In addition, we realized that a debut novel may not be the most representative version of a translated work.

We also discovered that there are differences when the translator is a native speaker translating to English or if an English speaker has learned another language.

The most intriguing translation situation is with Donna Leon. When I first started the group, her works hadn’t been translated into English in paperback version. So I listened to an audiobook version of Death at La Fenice (1992) on CD read by Richard Morant (2003). It was the WORST translation I have ever heard. The English was choppy and included bizarre idioms and archaic language. A year later, the paperback version (2004) of the book came out in English and I discovered that the audiobook had been translated from German to English. The crazy thing is that Donna Leon is an American who has lived in Venice most of her adult life. She writes in English and her protagonist is a policeman in Venice, Commasario Brunetti. There are close to 20 books in the series. Her works have never been translated into Italian.

Lynn: What are your three top women mystery writers in translation? What are your favourite books by these writers?

Phyllis: My three top recommended international women mystery writers in translation are:

Helene Tursten from Sweden: We have read three or four of her works and the most popular among the group was An Elderly Lady is Up to No Good (2013) translated by Marlaine Delargy (2018), about an octogenarian serial killer. Mod is a true psychopath who you will love!

Karin Fossum from Norway: The Indian Bride (2000), translated by Charlotte Barslund (2007), was about the murder of a mail order bride. It was one of the most haunting books we have read in our 14 years. It is not just the death of a woman on the first day being in her husband’s native land, it’s the longing and human sadness that touches you.

Fred Vargas (the pseudonym of the historian and archaeologist Frederique Audoin-Rouzeau) from France: A highly imaginative and comedic mystery, Seeking Whom He May Devour (1999), translated by David Bellos (2004), is a must read for the characters alone, one of whom is an African orphan raised in a remote village in France, whose basic knowledge of language is from a dictionary he carries everywhere. His interpretation of the world is like no other. What is also quirky is that the French title of the book is L’Homme a l’envers, which translates literally to “The Inside-out Man”, while the American title is a biblical reference (1 Peter 5:8).

One of the most interesting things we’ve found is the translation of titles. For instance, the original title in Swedish of Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2008) is The Men Who Hated Women (2005), which was translated by Reg Keeland (a pseudonym for Steven T. Murray – another eccentricity in the translation world!). Perhaps marketing or a nonsensical idiomatic translation are the main reasons titles can be so different from the original titles in the original language.

Lynn: So can you give us a sneak preview of other women writers in translation coming up next year?

Phyllis: In the new year, we will be reading Butter: A Novel of Food and Murder (2017) by Asako Yuzuki, translated by Polly Barton (2024). Based on the “Konkatsu Killer” [case in Japan], this is one for the foodies and explores the impossible beauty standards for Japanese women.

Although written in English with Navajo language, another book we will read is Exposure (2024) by Ramona Emerson. We read Shutter (2022), Emerson’s first book, a couple of years ago, which was a great venture into Navajo culture and the supernatural.

Lynn: How can new members join?

Phyllis: September’s Book Club book is The Lagos Wife (2023) by Vanessa Walters. This book is not in translation because Vanessa Walters is Afro Brit from the Caribbean. Interestingly, the original title of the book was The Nigerwife, but the US publisher changed the title because many Americans were mispronouncing the title, making a racial slur.

Those interested can contact Gloria Melnick (gloriamelnick@gmail.com) to join the International Mystery Book Club. From them, you can join the group via e-mail. It meets online via Zoom at 7pm Eastern Standard Time on the third Tuesday of every month.

Please join me – “the Benevolent Dictator” – and a great group of mystery readers!

If you have any questions, contact Lynn Lawrence-Brown (lynnlawrencebrown@gmail.com).