by Jack Zipes

I never expected to meet Gianni Rodari, and unfortunately I never did meet him. Nevertheless, he is a real force in my life, a life force, as are many other people whom I have encountered and who have compelled me to rethink the purpose of my life and work and to alter the narrative and direction of my life. This is the reason why I want to talk about my various encounters with Rodari to explain how and why his work captured my imagination. Obviously I cannot totally explain all these encounters, nor do I want to. But these encounters form a kind of narrative that will allow me to introduce and comment on his work and to clarify why I have called him “the devil’s advocate as the patron saint of children” in the introduction to The Grammar of Fantasy. There are few writers in the world who have spoken out for children the way Rodari has, and through all his works children’s urgent and optimistic voices can be heard.

My first “meeting” with Rodari was about 1981, the year after he had died. I was in the midst of collecting different versions of Little Red Riding Hood for my book The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood. I was scouring libraries, flea markets, bookstores, archives, and collectible shows for interesting versions of this tale to explain why readers from the eighteenth century to the present were fascinated by it, and at one point I came across a version that begins like this:

Once upon a time there was a little girl called Little Yellow Riding Hood.

“No! Red Riding Hood!”

“Oh yes, of course, Red Riding Hood. Well, one day her mother called and said: ‘Little Green Riding Hood—’”

“Red!”

“Sorry! Red. ‘Now, my child, go to aunt Mary and take her these potatoes.’”

“No! It doesn’t go like that! ‘Go to Grandma and take her these cakes.’”

“All right. So the little girl went off and in the wood she met a giraffe.”

“What a mess you’re making of it! It was a wolf!”

“And the wolf said: ‘What’s six times eight?’”

“No! No! The wolf asked her where she was going.”

“So he did. And little Black Riding Hood replied—”

“Red! Red! Red!!!”

[ … ]

This remarkable Rodari story was first published in English in the children’s magazine Cricket in 1973, and I had come across it in 1981 when I knew next to nothing about Rodari. I did not know Italian, and I did not know how Rodari’s tale fit into his pedagogical theory. For me, his story was appealing because it played with the traditional fairy-tale motifs and challenged standard forms and notions of storytelling. It was simply charming, deceiving in its simplicity, and one year later, in 1982, I realized just how much more there was to the tale than I realized.

I was in a Paris bookstore, browsing in a section that dealt with pedagogy, and I came across a book titled Grammaire de l’imagination by Gianni Rodari published by Français Réunis in 1978. I immediately recognized Rodari’s name, picked up the book, and intuitively realized that this book might have some sort of crucial significance for me, especially since I believe in something like elective affinity. So I purchased the book and read it that night. All of a sudden it became clear to me, particularly after reading the chapter “Little Red Riding Hood in a Helicopter,” why Rodari had written this tale – called “Telling Stories Wrong” – and why it was so representative of his innovative work with children and his own literary efforts. I could now see that Rodari was not simply mocking the traditional fairy tale, but that the tale emanated from his notion of the fantastic binominal, two seemingly mismatched words that, when put together by chance, can stimulate children and adults to explore the depths of their imaginations and their potential to create stories. In this case, Rodari demonstrated how Yellow and Riding Hood can lead to other unusual combinations that can form a comment about storytelling and the expectations of children. In this particular case, he wanted to challenge children’s ideas about a fixed way of telling a fairy tale, to emancipate them from the constraints for formulaic narration, to give them a sense that they can become their own storytellers and play cheerfully with motifs, topoi, and characters that have been handed down to them from adults.

Rodari’s Grammaire de l’imagination or Grammatica della fantasia now became my bible. By 1982, I had begun to do a great deal of storytelling in schools, and Rodari’s suggestions and ideas about animating children to express themselves in imaginative ways formed the basis of my approach to storytelling. The more I read Grammatica della fantasia, the more I learned and explored new avenues of stimulating not only the imagination of children but also my own imagination. Moreover, Rodari taught me to how to learn from children and learn humility in working with children. By 1986 or 1987, I wanted very much to translate Grammatica della fantasia and sent a proposal to an editor I knew at Random House to try to convince her that I could do a translation of Rodari’s Grammatica from the French, but she was unfortunately (or fortunately) not interested. Given my work schedule and other projects, I put the Rodari translation project on the back burner, although he was always with me and I continually referred to his book when I needed some new inspiration in storytelling.

Some years passed, and I was again in Paris on a research grant. It was 1989, and I was invited to give some talks on fairy tales at universities in Venice and Florence. Since I had known about this trip for several months, I had been studying Italian, and I was eager to see whether I would be able to communicate with people and read some children’s books written by Rodari. It was spring, right before Easter, and as I spent some time exploring the bustling Florentine streets, I came to the university district, to a large square and saw a big banner with Rodari’s name on it. I blinked. I was stunned. Another encounter with Rodari. There was a huge exhibit at the university with fabulous works done by children and teachers, inspired by the works of Rodari that were also on exhibition. It is difficult to imagine all the drawings, nursery rhymes, paintings, fables, fairy tales, skits, designs, proverbs, and music that Rodari had fostered, even after his death, for Rodari is still very much admired by Italian teachers, and his Grammatica still used by many educators.

It was fate, I said to myself. Something keeps driving me to Rodari. I had to improve my Italian and become more conversant to be able to immerse myself in his works. So, much to the surprise and delight of my wife and daughter, I scheduled my next sabbatical for Florence in 1994-95. Since I knew this was going to be my pivotal Rodari encounter, I threw myself into intensive Italian courses as soon as I arrived in Florence. Now I was able to learn more about Gianni Rodari’s life, and I learned that he was the son of a baker and was born in 1920, that he lost his father when he was ten years old, that as a young teacher he had difficulties with the rigid educational system in Italy, that he joined the Resistance and Communist Party about 1943, that he stumbled on to writing stories for children in 1948-49, when he was editing a Communist newspaper, and that he went on to become the foremost innovative writer for children in postwar Italy until his unfortunate death in 1980. I read about his difficulties with the Catholic Church and conservative politicians who fought progressive school reform. I read how he sought to gain access to the schools and to encounter children in schools and invent stories with them. I learned about his humility and modesty, his struggles and contradictions as a political thinker, writer, husband, and father.

The more I read about Rodari and by Rodari, the more I became convinced that I had to proceed with translating Grammatica della fantasia even though I did not have a publisher for the book. So, my sabbatical year was spent immersing myself in Rodari’s works, and thanks to Herb Kohl who put me in touch with Teachers and Writers Collaborative and thanks to the encouragement of Ron Padgett and Chris Edgar, who saw rough drafts of my translation, I was able to complete my work during the summer of 1995, and Teachers and Writers agreed to publish it.

To the end of his day, Rodari tried to be the patron saint of children without being patronizing. They were his source of hope and rebellion in all his encounters with them. And these encounters also provided the creative sparks for his writing. They fed his imagination, and he repaid children by writing some of the most memorable stories, poems, and novels in Italian literature that convey children’s need and dreams for a better world. But Rodari made it clear that their need is our need, that if we neglect and abandon children, we are in effect denying our own humanity. And humanity is what mattered most for Rodari, and as he tried to show, humanity is at the heart of any true grammar of the imagination.

This is an excerpt of the talk Professor Zipes gave in Richmond, Virginia to the Children’s Literature Association in 2007.

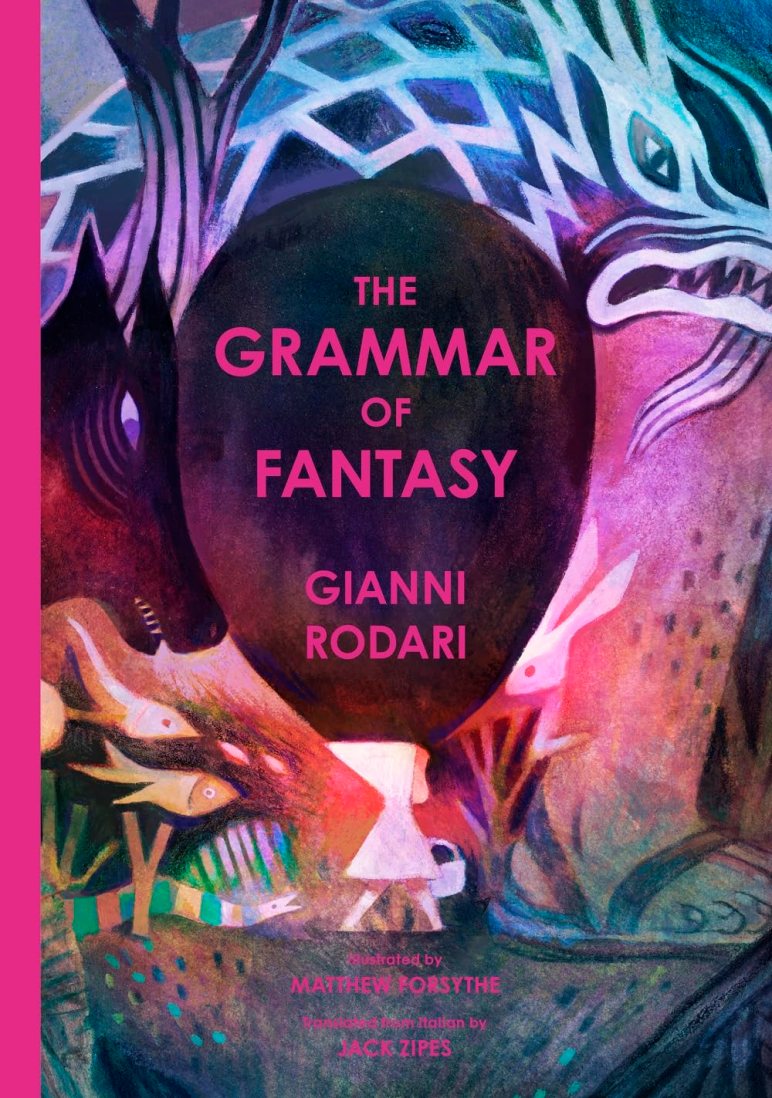

The illustrations, by Matthew Forsythe, are from the forthcoming new edition of The Grammar of Fantasy, translated by Professor Zipes.

The Grammar of Fantasy: An Introduction to the Art of Inventing Stories

- by Gianni Rodari

- Translated from the Italian by Jack Zipes

- Grammatica della fantasia. Introduzione all’arte di inventare storie (1973)

- Illustrations by Matthew Forsythe

- Publisher: Enchanted Lion

- Pages: TBC

- ISBN: 9781592703050

- New edition forthcoming, on March 11, 2025

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Pre-order the book here.

Jack Zipes is Professor Emeritus of German and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota and has published numerous books dealing with folklore and children’s literature. In addition to his scholarly work, he is an active storyteller in public schools and has worked with children’s theaters in France, Germany, Canada, and the United States. In 1997 he founded a storytelling and creative drama program, Neighborhood Bridges, in collaboration with the Children’s Theatre Company of Minneapolis that is still thriving in the elementary schools of the Twin Cities. His most recent book is Buried Treasures: The Power of Political Fairy Tales (2023), which includes an essay on Gianni Rodari.

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

One thought on “#ItalianLitMonth n.40: Jack Zipes: Encounters with Gianni Rodari and His Grammar of Fantasy”