by Alex Valente

Each step will be harder than the last. The first is undoubtedly the easiest. All it takes to find the Eternal Gate is to lose your way.

But fear not, traveler: if you are reading these words, it is very likely you are already, in your own way, lost…

I started playing games that involve telling stories while rolling dice all the way back when I was still just an Italian teenager. My very first venture lasted maybe three afternoons, as the game didn’t fully stick with some of the people in the group. I didn’t really play again until several years later, when I embodied a vampire in a live action role-playing (LARP) game set in my hometown; I kept courting role-playing games (RPGs) through university in the UK, and found out that I really, really liked playing pretend with a bunch of other people. It wasn’t until I moved to Canada at the tail end of 2019 that I stopped dipping only my toes and took the full plunge into the RPG pool and community, just in time for its explosion in popularity with the peak of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, Acheron Games approached me, almost in a panic (such is the nature of the beast), to help with the translation of a fascinating RPG project that needed doing as quickly as possible, as their previous translator had suddenly pulled out. The project was, as pitched, a setting book for a role-playing game (based on the 5th edition ruleset of Dungeons & Dragons, right before a nasty debacle that I will not recount here) adapting the entirety of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno from the Divina Commedia into a playable world, complete with characters, monsters, plot hooks, and mechanics to emulate the loss and gain of divine hope. I am not Michael Palma, the Divine Comedy is not among the works I have (or want) in my portfolio, but I do know and like RPGs. And I love trying to find or emulate a coherent storytelling voice in my games and in my literary work. I said yes. I translated the quickstart guide (in RPG parlance, usually: a sample of the game with simplified rules, ready-to-play characters, and a short introductory adventure) in time for the project to enter its crowdfunding phase.

My contribution for the wider project, other than rewriting the entire thing exactly as it is except for all the words, was also to find all the parts of the text already existing in English and in the public domain, so that the publisher could include it in a book to be sold to audiences. The best option, also suiting the tone and atmosphere of the game, ended up being Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1867 translation of Inferno. Which also meant I had two voices to emulate in style and register, while also keeping the language as clear and understandable to a player audience as possible. (Note: I did not, in fact, translate the rules-heavier side of the books, as the language is almost technical in nature and Fiorenzo Delle Rupi is a specialist with much more experience than me on that; games are a multi-headed beast, I am but one of the faces!) Such is the balancing act of many a literary translator’s process, but unlike my previous work with novels and stories, I was providing a gaming experience rather than immersing the reader into a continuous narrative. My voice, my words slip even further into the text, waiting to be reinterpreted and read out, chiselled and enacted by a table of people who really want to experience Dante’s world building, his sensibilities, and the work he has inspired since. I was playing a game with myself, using the text(s) as guidelines and my own experience as a role-player and games master to add flavour, flourishes, and – at times – fun Easter eggs for myself, as all translators do, but also to aid new players (the Lost Ones, in the case of Inferno) and games masters (The Guide) to bring out the most of the original text, the game texts, and the game itself at the table.

Inferno may be something of an outlier in its literary specificity, but there are many others contributing to the Italian renaissance pouring into the anglophone role-playing world. Acheron Games also publishes Brancalonia, a farcical “spaghetti fantasy” that borrows from Italian folklore, Western films, and pop culture; there are also the likes of Mana Project Studio (with whom I’ve worked on Historia), Two Little Mice (who also worked on Apocalisse), Need Games, and World Anvil, to name but a few with some international recognition. There are also many other translators helping the anglophone world discover what Italians are cooking, such as Camilla Zamboni, Caterina Arzani and Ian Hathaway, and others working in the other direction, allowing for and facilitating cross-pollination, like Marta Palvarini and Laura Fontanella. All enabling the discovery of folklore, local legends, re-visitations, and re-elaborations, in a much smaller world than one might initially think.

I was recently reading a conversation between a number of people I regularly discuss games with, on one of the many – too many – Discord servers I find myself in, and someone (Zeb Clifton of Titanomachy: Dreams of the Hue) wrote a message that stuck with me: “everybody knows how to play pretend; games are just what we buy to tell ourselves that’s not what we’re still doing”. Literary works are a codification of those pretend spaces in which authors operate, sometimes drawing from popular or general imaginaria; Dante and his Inferno are perfect examples of this. Games such as Inferno – and even its spiritual successor, Apocalisse – provide the next step, a re-opening to interpretation, to the telling of stories within the codified frame. A way to engage with something that has haunted and influenced literary landscapes, beyond the code, beyond the canon, truly making it one’s own by playing pretend in someone else’s imagination. Translating this type of work, both the literary and gamified layer, is just how I buy into telling myself I’m allowing others to do the same thing.

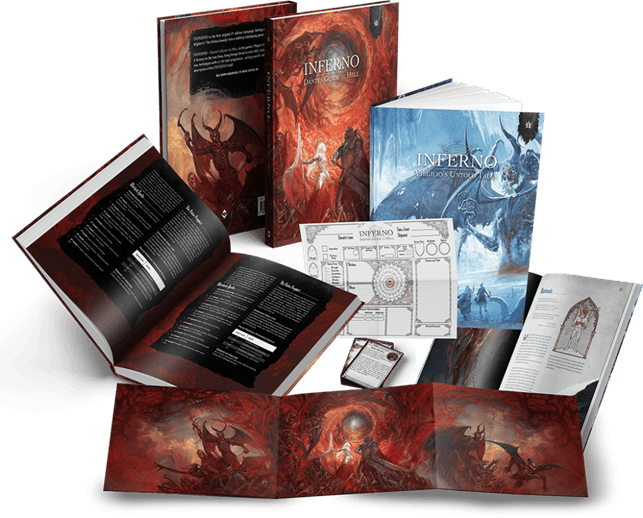

INFERNO – DANTE’S GUIDE TO HELL

Developed and produced by Acheron Games with Epic Party Games and Two Little Mice (2022)

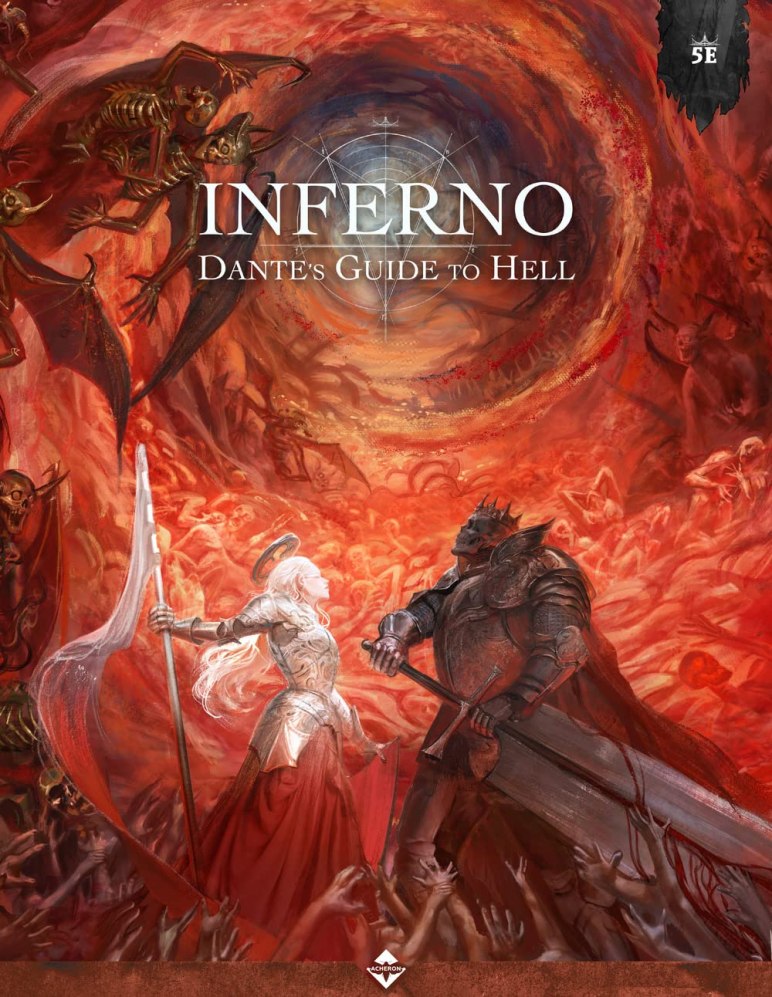

Inferno – Dante’s Guide to Hell (the “Red One”) is the “Player’s Handbook” and completely focuses on character creation and options, setting rules, and a deep description of the Inferno itself. It could be read by players, and it explains why the PCs are there, who they are, what they could do in hell, and how to leave this supernatural realm.

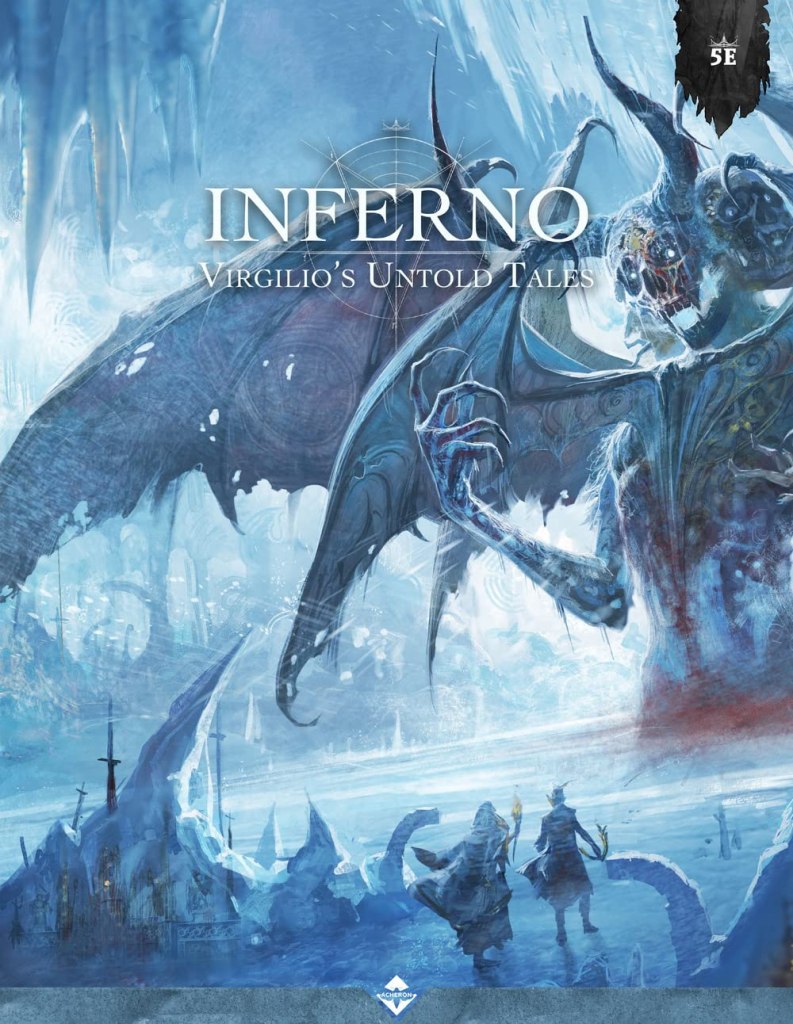

Inferno – Virgilio’s Untold Tales (the “Blue One”) is the “Game Master’s Guide” + “Monster Manual”, with adventures, perils, game hooks, special equipment, a whole campaign frame, and a bestiary, together with a deeper description of the Inferno as a sandbox to be used after the end of the campaign.

Note: Both books are required to play through the Inferno adventure. The Quickstart, however, is free to download, standalone, and contains everything you need for a game.

The Inferno Quickstart is the introductory publication to Inferno – Dante’s Guide to Hell for the fifth edition of the world’s most popular tabletop role-playing game, freely inspired by the imagery and setting created by Dante Alighieri for The Divine Comedy.

Download the Quickstart Guide, Map of Hell and Character Sheet for free here.

Other Works Mentioned

- Apocalisse – John’s Guide to Armageddon (Acheron Games, 2024)

- Apocalisse – Monsters of the Armageddon (Acheron Games, 2024)

Alex Valente (he/him) is a bisexual bilingual Britalian living on xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ land. He has been a cleaner, publishing intern, waiter, scare actor, editor, university lecturer, language teacher, shop manager, and is more usually a translator. He can be found in tiny writing on the credits page of books, when publishers remember to name the translator, and lurking in TTRPG spaces, when people forget he’s there.

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

2 thoughts on “#ItalianLitMonth n.37: Playing Pretend in Dante’s Inferno (and Other Italian Stories)”