by Clarissa Botsford

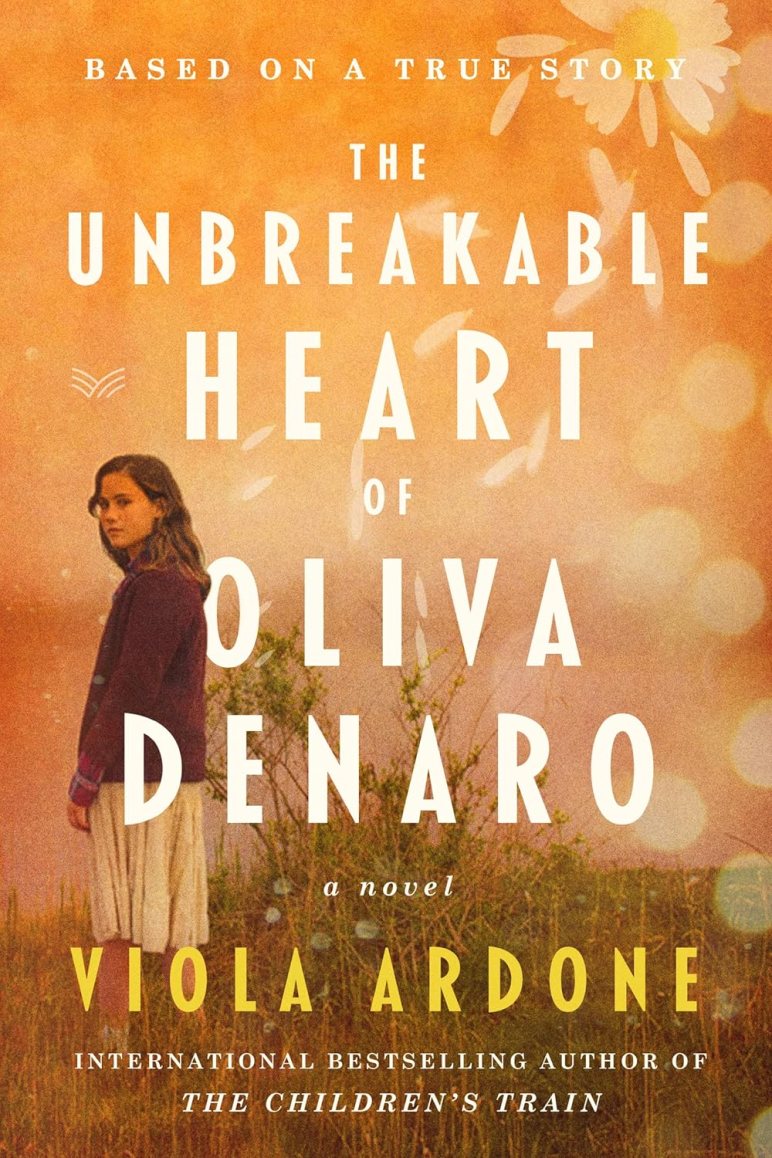

The Unbreakable Heart of Oliva Denaro by Viola Ardone is a novel about consent: a living and breathing testament to the #NoMeansNo and #MeToo movements.

It’s the kind of book that people read in one night and then pass on to friends. It also lends itself to class and book-club discussions precisely because it approaches the issue of consent so delicately that everyone can contribute to the discussion, no matter where they stood before reading the book, including teenagers, as the protagonist had just turned sixteen when the events described in the novel changed her life forever.

The author is a high-school history and literature teacher and, by shifting the story to a period in the past (the early 1960s) and to a southern region of Italy (Sicily) that people may consider culturally “backward”, she quietly prepares her readers to grapple with the delicate subject matter with an open mind, almost as if being one step removed helps being able to talk about it by distancing it. Once they are gripped by the story, they come to realize how contemporary the subject matter is and how relevant it is today to boys and girls, men and women, all over the world.

Oliva is born a fraternal twin: her brother is free to run wild and do what he likes, while she is hemmed in by societal norms from an early age. Not even being able to go to school is a given. The unfairness of this fluke of birth is a theme that the author insists on from the first line of the novel, giving the free-spirited and fiercely intelligent Oliva the narrative voice throughout, until there is a shift in time and in point of view towards the end of the novel.

Oliva is warned constantly by her mother of the dangers lurking out there in the world, and told to keep her eyes to herself, to look down, to walk primly, to dress properly, never to dance or sing, and above all, to prepare to be a good wife. Unfortunately for Oliva, her very spiritedness and refusal to bow to her mother’s dictates is what attracts unwanted attention. The older boy whose father owns the local cake-shop feels entitled to take a shot at her, enjoying the challenge of “breaking her in” against her recalcitrance. At every step she says No and at every step he assumes she means Yes, that she’s just being a tease, that really she wants him but doesn’t want to appear keen, or upset her mother — and you can probably guess how the story goes as the situation is as old as history itself.

Not only is Oliva not “broken in”, but she breaks with tradition and history, which is what the title of The Unbreakable Heart refers to. Oliva goes against every fiber of her upbringing, against custom and community expectations, when she rejects the offer of “reparation” through marriage, a practice and a law (“marry your rapist”) that was not repealed in Italy until years later, and is still in place in many societies today, as the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) highlights. Focusing on bodily autonomy, or people’s right to make their own choices about their own body, a 2021 report found that 45% of women in 57 countries are denied the right to say yes or no to sex with their partner, use contraception or seek healthcare.

When Oliva, with the constant and unflinching support of her father, takes the case to court, we all know she is doomed to lose, just as we all know that the burden of proof in rape cases is impossibly skewed and that the victim is more often than not blamed. Yes, she did lift her eyes, yes, she did speak to him, yes, she did accept one dance with him.

Her uphill struggle doesn’t end there: she keeps her head high, even after her family is first ostracized and then forced to move out of town; Oliva goes on to study and returns to take up the position once occupied by her beloved elementary school teacher, Rosaria.

Oliva’s unbreakable heart contributed to the repeal of the “marry-your-rapist” law in Italy in 1981. The novel is, in fact, a true story.

The Unbreakable Heart of Oliva Denaro

- by Viola Ardone

- Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford

- Original title: Oliva Denaro (2021)

- 352 pages

- Publisher: HarperVia 2024

- ISBN: 9780063276871

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

Reviews:

Viola Ardone’s first best-selling novel, The Children’s Train (HarperVia, 2021, also translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford) has been made into a film directed by Cristina Comencini, and will be released this Fall on Netflix.

Click here for a reading of The Children’s Train with the author on the Translators Aloud channel.

Here are some possible discussion points to get people passionate.

What do you think of Oliva’s mother in this novel? Does she love Oliva or is she only concerned with her family’s reputation? Given the circumstances, what could she have done differently? Were her actions, ultimately, dictated by her own experience?

What does Oliva’s sister, Fortunata, symbolize in the novel? Is her name significant in this respect? Do you think Oliva’s actions helped free her, or did she come to realize for herself that she was in a trap?

Discuss the role of Oliva’s father in her upbringing? Who “wears the pants” in the family? Do you think the author portrayed him in a way that is deliberately deceptive? How does the final section, which is in his voice and seen from his point of view, change your perspective?

Liliana comes from a “communist” family that is more modern and open-minded than others in town. Were you surprised by this? In what other ways is Liliana and her family different from the rest of the town? What do you think of the town meetings and the discussions held there?

In what ways is Oliva’s elementary school teacher influential in her life? Do you think that school teachers in general play an important role in society and is this recognized? Why/Why not?

In what ways does the author portray Paternò’s sense of entitlement? What does the sprig of jasmine he tucks in his ear suggest to you?

Do you think a part of Oliva wanted to be noticed by Paternò? Did she in any way send “mixed messages” in his direction?

Oliva is actually kidnapped and held prisoner by a woman. For what reasons do you think a woman might aid and abet a man like Paternò?

Do you think Oliva’s behavior once she is rescued and back home is normal? Does she display any symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder? What are they? Maddalena and the lawyer took on Oliva’s case because they were fighting a cause. Do you think they persuaded her to take the case for their own selfish reasons? Did Oliva do the right thing by accepting it? Why do you think rape cases are so hard to prove?

Clarissa Botsford holds MAs in Modern and Medieval Languages from Cambridge, Comparative Education from the Institute of Education (London University) and Intercultural Studies from Rome, La Sapienza. A taste for literary translation developed later in life, after decades of non-fiction translating and teaching English and translation at the University of Roma Tre in Rome. She went on to win a Pen Heim grant, was short-listed for the Crime Fiction in Translation dagger and was a finalist in the 2022 ALTA Italian Prose in Translation prize. She has translated novels by Elvira Dones, Viola Ardone, Alessandro Baricco, Erica Mou, Concita De Gregorio, Sacha Naspini and Lia Levi. Clarissa is also a musician, as well as a Humanist wedding and funeral celebrant and celebrant trainer.

Follow her @bot_cla

“Italian literature in translation is hot this year, with Italy Guest of Honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Librarians, teachers and book-clubbers: spread the word!” —Clarissa Botsford

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

2 thoughts on “#ItalianLitMonth n.31: No Means No, or Does It? A Moving Testament to a Young Woman’s Courage”