by Wendell Ricketts

In 2009, the mononymous Italian singer-songwriter known as Povia came within a hair’s breadth of winning that year’s Sanremo contest, the annual “festival of Italian song,” a much-celebrated competition named for the coastal town in Liguria where it takes place. Sanremo is sort of a cross between The Lawrence Welk Show and America’s Got Talent, and scandal is always welcome at the festival, which lasts five long nights. Great performances and mediocre ones, venerated guest stars and, of course, Sanremo gossip and controversy become café and dinner-table conversation all across the country. Sometimes kerfuffles center around who was snubbed by not being invited, who was too old to sing, who allegedly had an “in” with the judges or, as was the case in 2009, the songs themselves.

That year, Povia entered a composition of his own entitled “Luca Era Gay” (“Luca Was Gay”), an ex-gay anthem heavy on discredited psychological theories about “close-binding” mothers, absent fathers, childhood seduction, and other tropes. The song’s theme and title were announced well before Povia appeared on stage to sing at Sanremo, but the full text had been guarded like the whereabouts of Bin Laden until about twelve hours before the festival began. And as soon as the lyrics were released to the media, the heavens (as Italians say) opened.

In advance of his official Sanremo performance, Povia had been working doggedly to keep his name in front of the public, giving interviews in which he argued that he was being persecuted for defending “family values” and claiming, first, that the song was autobiographical, then that he’d heard the story from a stranger he met on a train. (For anyone who cares: It all works out for Luca. He meets a nice woman who makes him feel “like a real man” and they get married.)

After the 2009 festival, Povia went on to found “no gender” conferences, opine that earthquakes were caused by the weight of too many people on the surface of the Earth, warn that Italy was falling into the hands of the Chinese, and inveigh against COVID vaccinations and masking protocols. In other words, you’ve heard this tune before.

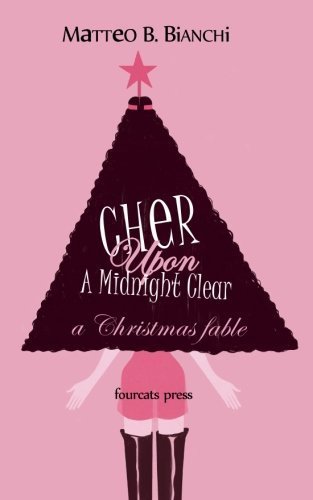

But I knew of another Luca, the eight-year-old hero of Matteo B. Bianchi’s 2006 “Christmas fable for grownups,” Tu Cher dalle Stelle, which I translated as Cher Upon A Midnight Clear, published in 2014.

Starting with music is appropriate for a discussion of Tu Cher dalle Stelle because the title of Bianchi’s book is a pun on a venerable and beloved Italian Christmas hymn, “Tu Scendi dalle Stelle,” whose text dates back to 1755 and to its author, Alfonso Maria de’ Liguori, then a Bishop and, in 1839, canonized by Pope Gregory XVI: “Tu scendi dalle stelle, o Re del Cielo” / “You come down to us from the stars, oh King of Heaven.” In choosing a title for the English translation, I, too, looked for a Christmas song that everybody knew—but one into which I could figure out a way to insert the name “Cher”.

Bianchi says he wrote Tu Cher on something of a dare: an editor at Playground, the book’s Italian publisher, suggested he write a “fairy tale for adults,” and Bianchi took up the challenge without an idea in his head and without giving much thought to what he’d write. (Though Cher was officially published as a “Christmas fable for grownups,” it’s more than appropriate for kids.) Two years later, he delivered a manuscript, a story he centered on “the innocence of a child and the distortion of that innocence by an adult world so cynical that it had even corrupted Christmas”—and on the magic of a “glittering cascade of sequins” and an “outrageous hairdo” who saves the day: Cher in person.

But let me back up.

Perhaps like all fairy tales, the plot of Cher Upon A Midnight Clear is simple. Each year at Christmastime, young Luca sends Santa Claus his letterina (Christmas list, or “little letter”, in Italian), but he never receives the toys he asks for. the gold wristbands worn by the fairies from the Winx Club (he got gloves and a Spiderman mask instead) or the Magic Hair Barbie doll whose coiffure could be cut and styled (he got a bicycle). As Cher Upon A Midnight Clear opens, he has his heart set on the white, thigh-high ice skates he spotted on Dancing with the Stars, but, when he tells his mother, her only comment is, “Didn’t you hear what your father said? That white skates are for girls?”

And Luca has a moment of reflection. “How do grownups know when something is for boys and when it’s for girls,” he wonders to himself. “Who tells them so? Where do they learn it? How come [I] can’t tell what the difference is, but it’s always so clear to them?”

What I found and continue to find so deceptively moving in Cher Upon A Midnight Clear is perhaps those few lines. Bianchi, who spent his childhood in a small town south of Milan in the 1970s, tapped into what I would call a collective or “tribal” childhood memory for many gay adults: being told that our tastes, our toys, our obsessions, our joys were not the appropriate ones—or, more pointedly, because the policing of sex-role behavior so often masks homophobia, that what we delighted in was “wrong” for our gender. In 2021, Dr. Henry Roediger, Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, described collective memory as something “held within individuals” that could reflect a knowledge base, an image of one’s people, and a process of deciding how the past should be remembered.

Pop music and pop-culture divas are surely part of gay collective memory, and Luca—even at eight years old—knows a diva when he sees one. He watches MTV with his brother, and he’s drawn to Cher’s music videos, especially the mini-movie for her 1998 hit, “Believe,” in which she saves the life of a distraught young woman whose heart has been broken. The woman in the video may not believe “she’s strong enough” to survive, but Cher knows better—and Luca believes in Cher.

Given Santa’s history of mistakes, then, it only makes sense for Luca to write a second Christmas letter to Cher, just as insurance. “I know children usually write to Santa Claus,” he tells her in his letterina, “and I also know he’s getting on in years and so we have to be respectful, but it’s not my fault if he keeps messing up my Christmas presents. So this year I decided to write to you, because you’re just as magic as he is, maybe even more, and I know you can help me get those beautiful white skates that I really, really want.”

Because Bianchi’s is a story with a happy ending, Luca’s letter finds its way to Cher, and, on Christmas morning, there’s a big package wrapped in red paper and purple ribbon under the tree. Inside are Luca’s skates. As Luca’s family begins to bicker over who got Luca the gift they had all decided against, Cher appears in a silver lamè dress and a pair of black patent leather boots with ultra-high heels. “All kinds of things seem impossible, but they happen anyway,” she assures Luca’s stunned family. “Think of this as a kind of spell.”

At the word “spell,” in fact, a change comes over them. “When I walk out that door,” Cher announces, “you’re all immediately going to forget I’ve even been here … and what you’re especially going to do is not make any more fuss about those skates. They’re just one Christmas present among all the others. Have I made myself clear?”

She has.

Luca’s Christmas is saved, but, in a more enduring way, so is Luca. Cher senses that something has been stifled in Luca, and she assures him that she doesn’t personally deliver presents to all the children who’ve been “really perfect” during the year, but rather to the ones she knows “are most in need of a present.” Like Luca. That’s her most powerful magic.

Perhaps the best story that came out of translating Tu Cher is this: the first publisher to whom I showed the translation was a man I’d become friendly with over several years. He owned and ran a small press based in Milan that had begun a line of books in English. I’d spent the holidays at his house and met his son (I’ll call him Antonio) who was eleven when I first knew him. The editor and I had spent a lot of time talking about the state of translation and about which Italian books might appeal to an anglophone audience.

He was enthusiastic when I first told him about Tu Cher dalle Stelle. Then he read it—and he was appalled. “Just because Luca likes dolls and white ice skates doesn’t mean he’s gay!” he insisted. “It’s terrible propaganda!”

What I think he might not have known is that, one New Year when I was visiting, Antonio invited me into his room, where he performed most of the soundtrack of High School Musical for me, a one-boy show complete with choreography, costumes, and stage business. For his dad, I suspect, Tu Cher hit too close to home: He was raising a Luca right under his roof, and he wasn’t ready to face it. (P. S. I’ve stayed connected with Antonio, who is now nearly thirty. He’s not only merely gay, he’s really most sincerely gay.)

Now Bianchi doesn’t come out and say that Luca is or will be gay (he’s only eight years old, after all), but the incriminating passage—the one that undid my publisher friend—comes when Luca asks Cher how he can ever repay her for his skates. “It’s like this, Luca,” she says,

Many years from now, when you’re all grown up, one day you’re going to march in a parade, you and a lot of other people. That day, you’ll be dressed just like me and you’ll be standing on a float. You’ll be wearing a wig and you’ll be singing my songs. I won’t be around anymore, but you’re going to give me the greatest gift anyone can give another person…. Thanks to you and to other friends like you, even after I’m gone I’ll still be alive in this world. The gift all of you are going to give me is called eternity.

It’s an “if you know, you know” moment, but hardly a subtle one. Of course, Luca isn’t predestined to be gay just because he “likes dolls and white ice skates,” but he’s also not predestined not to be gay, and that’s the point.

Povia’s Luca suffers, is tormented, feels his only hope is to change fundamentally because he has no room for his authentic self in his concept of a life. Perhaps both Lucas are content in the end, but only one of them has added something to his life rather than taken something away. Only one of them is likely to recall his youth with joy rather than with shame. Like Luca’s Christmas present, for Bianchi being gay is just one possibility among all the others. He creates a space in which Luca can be what he is, can choose his own way of being a boy and, eventually, of being a “real” man. With all due respect to Cher, perhaps that’s the greatest gift anyone can give another person.

Cher Upon A Midnight Clear

- by Matteo B. Bianchi

- Translated from the Italian by Wendell Ricketts

- Original title: Tu Cher dalle Stelle (Playground, 2006)

- 66 pages

- FourCats Press (2014)

- ISBN-13: 978-0989980029

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

Wendell Ricketts has worked as a translator from Italian since 1998. In addition to The Wrong Door: The Complete Plays of Natalia Ginzburg (U. Toronto Press), an early version of which received the PEN American Center Renato Poggioli Prize for translation, he is the translator of Woman Bites Dog: The Mafia’s War on Italian Women Journalists; Twenty Cigarettes in Nasiriyah: A Memoir; Trilobites: The Back To The Past Museum Guide; and various Giovannino Guareschi stories in the “Don Camillo” series (Pilot Productions). He is the author of What We Lost in the Fire and Other Stories and the editor of the anthology, Blue, Too: More Writing by (for or about) Working Class Queers.

“As the winners of the 2014 CEATL Spot the Translator competition put it: ‘words travel worlds.'” —Wendell Ricketts

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

One thought on “#ItalianLitMonth n.25: The Two Lucas”