by Jamie Richards

Recently I attended a packed celebration of Simon Hanselmann’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in Los Angeles where he concluded by exhorting everyone to “read more comics!” in order to ensure the continuation of the art form. Despite being one of the only consistently growing sectors in the book industry, and wildly popular among readers, graphic narrative tends to be considered apart from literature and excluded from the sphere of literary translation. Note that comics can safely be used to refer to the entire medium—any work, book length or strip, that combines words and images, of which the graphic novel is a subgenre. Because so many book-length comics are non-fiction, such as graphic reportage, I tend to use the term “graphic narrative” to generally describe these books. Of the international comics, Franco-Belgian BD and Japanese manga are the most widespread and best known, but many countries have their own extensive traditions, and Italy is no exception.

The ascendance of contemporary Italian graphic narrative follows parallel with the European tradition, developing out of early comic strips (Corriere dei piccoli) in the early twentieth century, and inspired by analogous international productions, particularly the American, Franco-Belgian, and Japanese, expanded into a rich tradition of widely read comic books often in popular genres such as adventure sold at newsstands. The post-WWII landscape produced its first Italian superhero (Asso di picche), and produced mega-phenomena like Topolino (Mickey Mouse), Diabolik, Tex, Dylan Dog, to name a few of the most famous among a rich and thriving scene, leading to the increasingly novelesque auteur series of the 1960s and 70s like Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese and Guido Crepax’s Valentina.

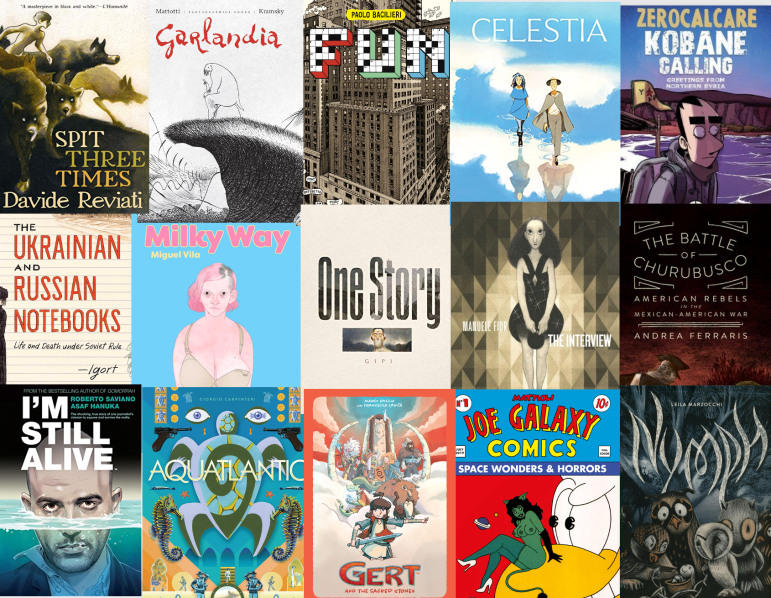

The modern era of the Italian graphic novel began to emerge in the late ’70s and early ’80s. An important forerunner is Andrea Pazienza, whose nihilistic, unrepentantly transgressive work introduced an underground sensibility to Italian comics; his romp Zanardi is available in English. Another from this generation whose incredibly fun (yet also X-rated) Joe Galaxy will be published fall 2024, preceded by the wordless Squeak the Mouse, part of Matt Groening’s inspiration for “Itchy & Scratchy” on The Simpsons. Other important creators from this period are Attilio Micheluzzi, whose war-themed works Marcel Labrume and Petra Cherie will be released in English in 2024 and 2025, and Guido Buzzelli, the “Goya of comics,” whose delightful, complex, satirical stories that draw on genre conventions to lampoon the present age are being published by the intrepid Floating World Comics in a precious three-volume collection. Included therein is his long story “Revolt of the Wretched,” a class parable which if more for depth than length is generally considered the first Italian graphic novel. Moving into the 80s, the Valvoline group represented a turning point from traditional heavy-lined cartoons to elegant painterly styles and of these creators Igort is the most prominent, whose varied oeuvre from the Neapolitan crime story 5 Is the Perfect Number to the testimonial-historical The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks is well represented in English. A short but fun recent book in this vein is Giorgio Carpinteri’s underwater crime fantasy Acquatlantic; a long and lush fantasy to come from this group of creators is Lorenzo Mattotti and Jerry Kramsky’s YA-friendly Garlandia about an invented group of creatures called “gars.”

The era of the proper graphic novel in Italy begins in earnest in the late 1990s-early 2000s, especially supported by the emergence of the comics publishing houses that would become major powerhouses on the Italian literary scene. A flourishing of styles and themes characterizes this very rich panorama, continuing into the present. Gipi’s My Badly Drawn Life made a major splash with its autobiographical black humor and its “badly drawn” revolutionary style; Land of the Sons continues in this visual style but as a fable about the end of the world and the loss of language. In other works his rough pen meets glorious watercolor drawings to create psychologically, historically intricate narratives like One Story. A scratchily-evocative style also defines Davide Reviati’s underrated yet monumental work Spit Three Times, about a young man growing up in the Italian provinces surrounded by the Romani community, whose history is interwoven into the book. The 2010s saw the emergence of rockstar-cartoonist Zerocalcare, whose ironic and accessible portrait of his generation has attracted legions of devotees in Italy. Readers in English can access some of his work: Forget My Name, Tentacles at My Throat, and The Prophecy of the Armadillo. His work has always had a significant punk-activist bent, and his chronicle of a volunteer trip to Syria, Kobane Calling, which in the comics-reportage style pioneered by Joe Sacco, documents the progressive Kurdish resistance in Syria. Manuele Fior, a contemporary sui generis creator seems to be inspired as much by intimist domestic fiction and modern art as anything, and his painterly works are an absolute delight to read: each is different, and in each color itself tells its own story. Celestia is arguably his masterpiece, but 5,000 km per second, The Interview, and Hypericum make for sublime reading. A highly literary graphic novel mixing the non-fictional history of the crossword puzzle with a fictionalized literary heist featuring a kind of Umberto Eco-double and the author’s alter-ego is Paolo Bacilieri’s wonderful Fun. A young master of the medium to look out for is Miguel Vila, whose Milky Way and forthcoming Comfortless provide unflinchingly grotesque, realistic portraits of Italian provincial life, the latter during covid. Finally, in a notably male-dominated scene where many fewer women creators have been translated, I would highlight Leila Marzocchi’s Nymph, a uniquely-drawn tale about a special creature amongst forest birds, talking trees, and the guiding Hand of Fatima. Picking up even a smattering of these titles, many of which have flown under the radar, would provide a solid sense of the incredible richness of the Italian comics scene.

Works Cited

- Paolo Bacilieri, FUN (SelfMadeHero, 2017)

- Guido Buzzelli, Collected Works, Volume I: The Labyrinth (Floating World Comics, 2023)

- Guido Buzzelli, Collected Works, Volume II: HP (Floating World Comics, 2024)

- Giorgio Carpinteri, Aquatlantic (Fantagraphics, 2020)

- Manuele Fior, 5,000 km per Second (Fantagraphics, 2016)

- Manuele Fior, Celestia (Fantagraphics, 2021)

- Manuele Fior, The Interview (Fantagraphics, 2017)

- Gipi, Land of the Sons (Fantagraphics, 2018)

- Gipi, My Badly Drawn Life (Fantagraphics, 2022)

- Gipi, One Story (Fantagraphics, 2020)

- Igort, The Ukrainian & Russian Notebooks (Simon & Schuster, 2016)

- Leila Marzocchi, Nymph (with Kim Thompson, Fantagraphics, 2020)

- Massimo Mattioli, Joe Galaxy (with Adrian Nathan West, Fantagraphics, 2024)

- Lorenzo Mattotti and Jerry Kramsky, Garlandia (Fantagraphics, 2018)

- Attilio Micheluzzi, The Farewell Song of Marcel Labrume (Fantagraphics, 2024)

- Davide Reviati, Spit Three Times (Seven Stories Press, 2020)

- Miguel Vila, Milky Way (Fantagraphics, 2023)

- Zerocalcare, Kobane Calling (Lion Forge, 2017)

Jamie Richards is a widely published translator from the Italian. She holds an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Iowa and a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Oregon, and her work can be found in numerous publications online and in print.

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

One thought on “#ItalianLitMonth n.13: Italian Graphic Narrative in Translation”