by Katherine Gregor

To read Part One of this article, click here.

If Italian dialectal idioms are sometimes hard to convey into standard Italian, translating them into English would make Hercules throw in the towel.

When considering how to translate dialect I rejected the option of using a UK regional dialect as an alternative because of its potential for creating inappropriate associations in the mind of the reader. Replacing source language dialect with an invented dialect or with a working class idiolect seems equally fraught with risk.

In Per una cipolla di Tropea the dialects help to bring the characters to life and to evoke the diversity of the seaport. I decided to highlight the fact that some characters speak in dialect by leaving a few words and phrases in the source language, but allowing the characters themselves to ‘translate’, as when Vercesi, sniffing the red onions, says:

“Bon odòr. They smell good.”

[Author] Alessandro Defilippi himself sometimes uses this strategy, for example:

“Dulsa” bofonchiò il maresciallo. “È dolce.”

However, I tried to keep the inclusion of original dialect at a level where it didn’t become intrusive.—Emma Mandley, Italian-English translator

Unlike, until fairly recently, in English, Italian regionalisms in spoken language do not tend to have connotations of social class. They are merely a sign of what, until one and a half centuries ago, was a political state in its own right, with its own way of dressing, its own cuisine, its own traditions and its own way of speaking. I must always remind myself that this kind of premise is unfamiliar to Anglophone, and in particular British readers, whose history is one of centuries-old political and administrative centralisation. If I chose to convey an Italian dialect through, say, Liverpudlian or Geordie, they could not avoid making social-historical-cultural associations that would be wholly inappropriate for a novel set in Italy. No regional English, Scottish or Welsh expression could possibly even remotely capture the culture, background and especially temperament of a Sicilian, Roman, Venetian or Milanese character.

In my translation of [Domenico Starnone’s] Via Gemito (Europa, 2023) I relied on several different strategies to capture Neapolitan dialect: I chose to leave longer obscenities in Neapolitan so they could retain their unfamiliarity and musicality; for frequently used noun-adjective epithets I made a keen effort to steer clear of any easy-to-identify cultural subset; for the ubiquitous phrase di questo cazzo I relied on both Italian and English depending where it appeared in the text (either before or after the narrator’s fantastic explanation of the phrase); in dialogue, where it would be so very easy to use slang, I refrained from using words like gonna, wanna, shouda again to keep my distance from any stereotypes. There are many ways of relaying what it means to be Neapolitan, and Americanizing Starnone’s language is not one I endorse.

—Oonagh Stransky, Italian-English translator

If I were to translate a novel written or set before the 19th century, I suspect I could potentially use, sparingly, English regional expressions that would have been used in a large swathe of the country, and could not be linked to a specific city or region. As I have, so far, translated mainly 20th and 21st-century Italian fiction, I have deliberately avoided trying to find a match for a dialectal idiom among any British regional expressions.

When I translated La cognizione del dolore [by Emilio Gadda] (The Experience of Pain, Penguin Classics, 2017), the problem of dialect arose, fortunately, with just one character, Colonel Di Pascuale who, we are told in chapter 4, was descended from a family of Italian origin that immigrated to Maradagàl (the fictitious south American country where the novel is set) at the end of the previous century. His language is impenetrable even in the original Italian and is largely there for the effect. The story is told by the narrator and the colonel’s blusterings provide a comic garnish.

I was helped by the advice of the eminent translator Michael Henry Heim who suggested creating a unique dialect through a combination of contractions, grammatical mistakes, and the like, to produce a speech pattern that had no distinct geographical identity but can still convey core information.

In the following example, the colonel has unmasked a fake invalid:

“…. Okkay boy, stop’t ’ere once and for’ll!… and dis maddness ’bout you bin deaf!…. Tall sturies git longr ’n longr…. den turn bad…. Now ’ere’s de evidence…. Two gud witnissis…. jus’ as law ricuires….” (the clerks fell silent)… [The Experience of Pain, Penguin, 2017, p. 118]

—Richard Dixon, Italian-English translator

Depending on the context of the original Italian, I sometimes opt for a colourful time, place, class and age-neutral colloquial expression to convey the message in dialect.

Oliva’s mother [in The Unbreakable Heart of Oliva Denaro by Viola Ardone, HarperVia] is rejected by all the “scissor-tongues” in the provincial Sicilian town because she is Calabrian. The challenge was how to render the gulf between two dialects when any attempt at finding regional equivalents in English would carry too many connotations and would be presumptuously culturally-specific (if I chose two regions in the UK, for example, would an Indian, Australian or American reader appreciate the differences?). Once it was established that the mother mutters imprecations or yells at her family in a Calabrian dialect that nobody understands when she is angry or frustrated — which is almost always — the solution was quite straight-forward: to reflect her character, social status and point of view in her direct speech and add to the reporting verb, “she muttered in Calabrian” or “she yelled in her dialect.”

—Clarissa Botsford, Italian-English translator

As a rule, and depending on the volume of dialect in the novel I am translating, I am inclined to leave as much of it in the original, in italics, either immediately followed by a translation or a paraphrase. Too many occurrences of paraphrasing can make the English version heavy, so, for the sake of elegance, when absolutely required, I have also been known on occasion to add a little something to the response of another character, so that his or her reaction makes the meaning of the words spoken by his or her interlocutor clearer. If this word or expression is used many times in the original text, I will paraphrase or translate it only once and trust the reader to remember its meaning either consciously or else absorb it into his or her imagination.

I often wish that Anglophone publishers were not so opposed to explanatory footnotes, especially when a dialectal idiom is particularly colourful or when it refers to an event in history or a religious belief. Returning to the subject of insults, what would be an Anglophone copy editor-acceptable translation of the Roman Mortacci loro? “Damn them”? Powerful message a couple of centuries ago, when summoning damnation on someone was the worst possible fate you could wish them, but nowadays diluted into your garden variety, unimaginative verbal abuse that far from reproduces the creativity behind Mortacci loro, which is not, in fact, a curse, but an offence to the interlocutor’s very ancestors for being a bad lot, a very bad lot.

Another favourite expression of mine in romanesco is E’ come cercà Maria pe’ Roma. Literally, it means, “Like looking for Mary in Rome”. “Like looking for a needle in a haystack” is such a poor equivalent and nowhere near illustrates the wild goose chase involved in finding a woman called Mary in a city that is the historical capital of the Christian Church. I know that when I read books in non-English translation, I welcome such titbits expanded on in footnotes. After all, reading a novel isn’t just about following the plot. As things stand in the current trend, we feel that footnotes disrupt the flow of reading. Perhaps, publishing budgets allowing for an extra page in the book, we could add a glossary of the most choice dialectal items featured in the novel, for those readers interested in etymology and history of language.

This article originally appeared in its entirety on newitalianbooks.it.

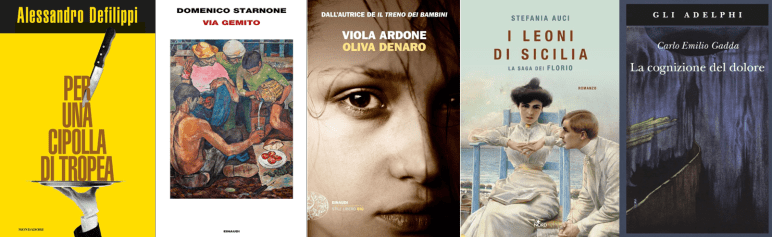

MENTIONED IN THIS ARTICLE

The House on Via Gemito

- by Domenico Starnone

- Translated from the Italian by Oonagh Stransky

- Original title: Via Gemito (2001)

- 480 pages

- Publisher: Europa Editions (2023)

- ISBN: 9781609459239

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

The Experience of Pain

- by Carlo Emilio Gadda

- Translated from the Italian by Richard Dixon

- Original title: La cognizione del dolore (1963)

- 256 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Classics

- ISBN: 0141395397

- Paperback edition forthcoming: 31 October, 2024

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Pre-order the book here.

The Unbreakable Heart of Oliva Denaro

(Look for Clarissa’s upcoming piece on this title in Italian Lit Month)

- by Viola Ardone

- Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford

- Original title: Viola Ardone (2021)

- 352 pages

- Publisher: HarperVia (2023)

- ISBN: 0063276887

- Treat your bookshelf to a taste of Italy! Order the book here.

Katherine Gregor is a writer of fiction, non-fiction and plays, as well as a literary translator from French and Italian. She was born in Rome, where she lived on and off for twelve years, spending six years also in France before moving to England in 1988, where she graduated from the University of Durham. She has also worked as a teacher of English as a Foreign Language, a press agent and an actors’ agent.

She also blogs at Scribe Doll.

Italian Lit Month’s guest curator, Leah Janeczko, has been an Italian-to-English literary translator for over 25 years. From Chicago, she has lived in Milan since 1991. Follow her on social media @fromtheitalian and read more about her at leahjaneczko.com.

One thought on “#ItalianLitMonth n.11: The Sorrows and Joys of Translating Italian Dialects: Part Two”