Rongorongo. Source: Wikipedia.

Even though my work is more about endangered scripts than those no longer in use, I love Rongorongo, a glyph system discovered over a century ago on Rapa Nui, a.k.a. Easter Island., which recently returned to the news through a rather breathless article in Smithsonian magazine.

What makes Rongorongo, which has so far resisted decipherment, so compelling is what I call the Stonehenge Effect.

When you visit Stonehenge, what may strike you as much as the eerie beauty of the stones is the behavior of the crowd around them. Stonehenge is almost always thronged with people, and they all have their heads slightly on one shoulder and they’re squinting at the stones, and lining them up with the sun, and pointing at various features on the horizon.

They’re responding to an enigma: just by looking at Stonehenge, anyone can see that it has shape and pattern. Pattern implies intention, and intention implies meaning–but we don’t know what that meaning is. The very shape of the structure becomes an unanswered question; we get captured by it. We try to resolve the enigma by finding its meaning, and until we do so, it nags at us. It becomes a kind of question mark, and a question mark is shaped like a hook: it won’t let you go.

Rongorongo consists of marks that are in some sense consistent (some more than others) and intentional. They clearly, like Stonehenge, exhibit pattern and intention and meaning. But nobody understands the pattern and can convert the forms into sounds, or into meaning. They are enigmatic, challenging, unresolvable.

So far, I’m all there with the Rongorongo excitement. Where I part company is when people start getting excited about what Rongorongo may imply about the history of writing.

One expert quotyed in the Smithsonian article wonders whether it is “a form of proto-writing, or a fully-fledged writing system.” The term “proto-writing” (and I’m indebted to Taras Grescoe for this analogy) is like the word “pre-history”: it implies that something that falls outside our range of information and our definition of value is worth less.

In this case, it implies that if a script is not phonetic (that is, it does not use a one-to-one written-symbol-to-spoken-sound correspondence), it hasn’t reached the stature of writing and by implication its creators were intellectually deficient. (As you’ll see in another of my columns for this month , one professor describes such kind of writing by using the word “primitive.”)

Rongorongo is a wonderful illustration of this nasty set of assumptions because we know absolutely nothing about it, so whatever we say is a form of projection, or prejudice. For all we know (a) it served its users perfectly well, and (b) it used ways of conveying information that we simply don’t understand or imagine.

Both these conditions are true for many graphic information systems that Western visitors/administrators/colonists/conquistadors regarded as inferior non-writing. Precisely because they were not based on trying to represent the sounds of spoken language, many of these forms had the wonderful virtue of being instantly comprehensible to people in multilingual regions and communities—a fact that colonial thinking turned on its head, and categorized their users as “illiterate.”

Moreover, as Sabine Hyland explains in the talk she gave for World Endangered Writing Day, Andean khipus were in many ways far more sophisticated than phonetic writing, using color, spatial relationships, fabric, pattern of knotting and even texture as means of encoding information—and doing so, moreover, using cheap, available, and highly portable materials.

There’s a strong argument to be made that such multidimensional forms represent an amazing future for communications—if only we weren’t so hung up on trying to replicate the sounds of speech.

A broader issue is that people developed a wide range of ways of communicating meaning, some phonetic, some not so. We have elected phonetic writing as a sign of civilization, but this is narrow and self-serving: if we use it, it must be the best, the most “evolved” method, the one that won out in the marketplace of ideas.

Not so. The Latin alphabet has become the world’s bully script because at crucial times and places it had more lawyers, guns and money than someone else. History is written by the winners—in the alphabet of the winners.

Thanks to a few imaginative and resolute anthropologists, we are starting to realize that the world is full of fascinating, complex forms of expression and communication that are far richer and more complex than mere phonetic, and these should be celebrated for the achievements they are, not condescended to because they have not gone down the narrow, flat, dull, colorless, mechanical, rather sterile path we have.

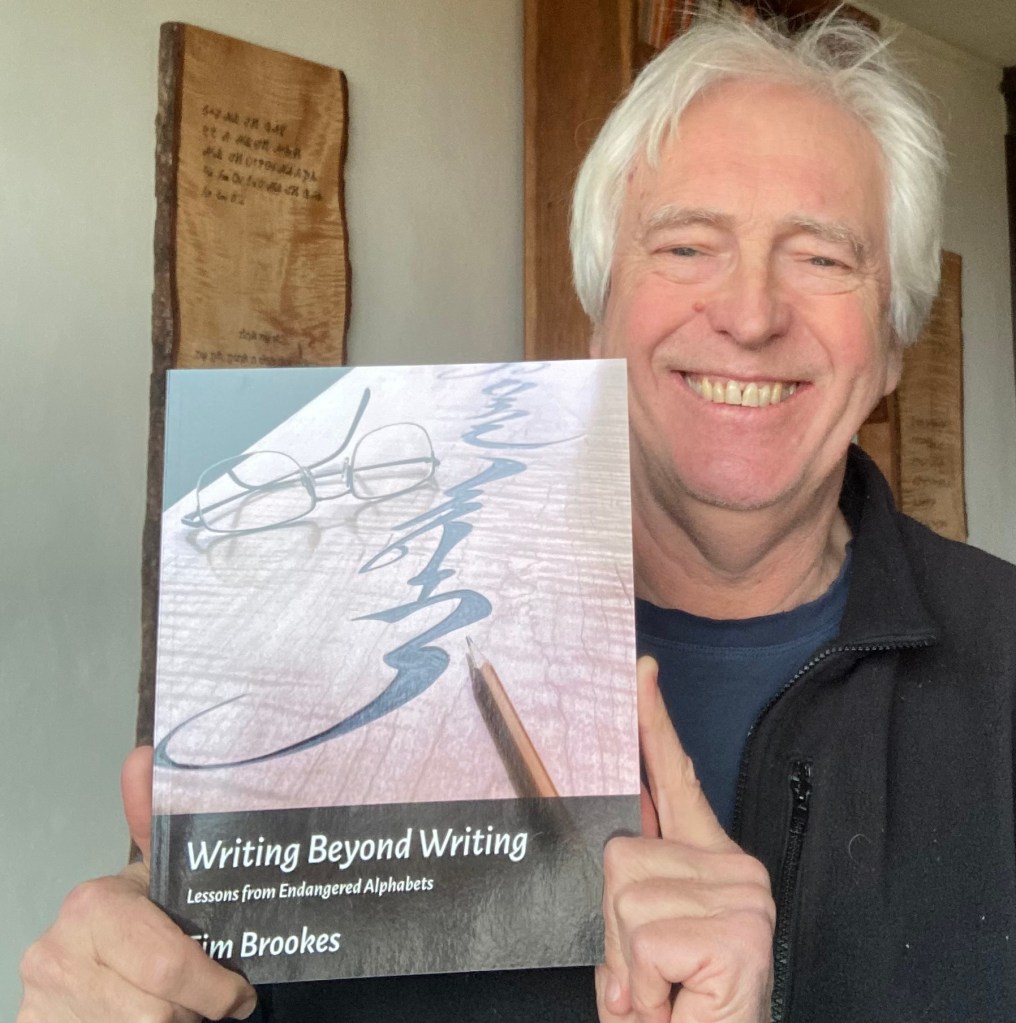

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.