Rembrandt, Moses, stone, God’s handwriting

Our sense of the extraordinary qualities of writing has sunk so much in the past century that when we hear how many cultures have traditionally regarded writing as a divine creation, a gift to the human race by a deity, we shrug it off as superstition and ignorance.

In a way, though, this simply shows how much more aware they are than we are of the extraordinary qualities of writing as an art and an invention, how intimately it is connected to the functioning of what we call society, religion, even civilization itself.

I’ve already quoted the high respect, even astonishment, with which the Mandaeans regard writing. But over in Southeast Asia, we see (thanks to Piers Kelly’s tireless field research) communities with an even keener sense of the value of writing–because they know what it means to have had writing, but to have lost it.

The Zhuang have a tale in which a god gave them both fire and writing (an amazing equivalence, given that we think of the arrival of fire as a defining moment in human evolution, yet the Zhuang put writing on a par with it), but not understanding either, they stored both in a thatched hut, whereupon the fire burned down the hut–and writing.

This catastrophe is recorded time and again in the cultural narratives of the Hmong, the Karen and the Chin peoples, vivid and even elaborate tales of the gift not valued, not guarded, lost through carelessness or enemy action.

“The Akha,” Kelly writes, “…kept their writing on buffalo skins but were forced to consume it while fleeing the invading Tai armies. The Wa wrote on oxhide that was eaten in hard times, while the Lahu wrote their letters on cakes that met the same fate. The writing of the Hmong was destroyed by the Chinese or eaten by horses, while Karen writing was variously stolen, eaten or left to rot. Similar stories of being cheated out of literacy and its presumed benefits are told by the Kachin, the Chin and the Khmu’.”

In some instances, the loss of writing is explicitly connected with the loss of status, land, and power. Another Karen tale attributes the loss of their script, or of literacy in general, to an ancestor who went off to work in the fields leaving an animal skin—a manuscript, in effect—on a stump of at the base of a tree, where the monsoon rains rotted it to such an extent that it was chewed by dogs and pigs and pecked by chickens. (The power of the writing was so great, its wisdom was said to have passed to the chickens that ate it, leading to the practice of divination using chicken bones.)

“Having thus lost the capacity to read and write, the Karen were easily dominated by the literate Burmese who expelled them from the lowland plains they had once inhabited.”

As I say, it’s easy for those of us in the dominant cultures to deride these tales as mythical and unscientific–tales for children, in effect–yet right at the heart of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, we have our own divine-writing-creation narrative.

In the book of Exodus, as you probably know, Moses rescues and leads the Israelites out of Egypt. They are a curious bunch: on the one hand, they appear to be God’s chosen people; on the other hand, they don’t behave like it. They are forever arguing amongst themselves, disobeying Moses and challenging him for the leadership. And if any other gods come along, then they’re pretty tempted to worship those. In other words, they are just one of many nomadic or semi-nomadic Middle Eastern people, getting by as well as they can.

The biblical wording here is fascinating. In Exodus 31, God gives Moses a series of very strict laws, and then in verse 18 (in a contemporary international translation), concludes, “When the Lord finished speaking to Moses on Mount Sinai, he gave him the two tablets of the covenant law, the tablets of stone inscribed by the finger of God.”

It’s an epic moment. The covenant, or contract, combines several extremely powerful forces: the stern word of God, the tough durability of stone, and, connecting the two, writing—not just the word of God, but the handwriting of God.

The divine origin of writing is not simply stated, it is insisted on. “Moses turned and went down the mountain with the two tablets of the covenant law in his hands. They were inscribed on both sides, front and back. The tablets were the work of God, the writing was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets.”

Yet, in a strong parallel with some of the other narratives I’ve referred to, man is weak and perfidious, and doesn’t appreciate the importance and the value of what is being offered. When Moses rejoins his people at the foot of the mountain, they have melted down all of their gold and jewelry and forged it into the shape of a calf, and they’re worshiping the calf.

At this point, Moses does something really interesting. He is so mad that they are challenging his leadership, and thereby are challenging the leadership of God, that he breaks the stone tablets. He destroys the writing of God. The implication is—they don’t deserve God, and they don’t deserve writing.

God’s reaction is equally interesting. He could have smitten the Israelites for defying his will, or he could have smitten Moses for breaking the tablets, but instead he addresses the crisis again through writing.

Exodus, chapter 34, verse 1: “The Lord said unto Moses, ‘Chisel out two stone tablets like the first ones, and I will write on them the words that were on the first tablets which you broke.'”

Moses chisels out a second set of tablets. In a seventeen-verse section, God spells out the terms of the covenant, or contract: God will drive out the Amorites, Canaanites, Hittites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites as long as the Israelites keep the ten commandments that are written on the tablets.

And finally, verse 27, “The Lord said to Moses, ‘Write down these words, for in accordance with these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel.”

This is a writing-creation narrative of a slightly different kind. It doesn’t claim that writing was invented by God—in fact there are passing references to writing elsewhere in Exodus—but it explicitly connects writing with authority, with the expression of God’s will as the basis of human law. As such, writing becomes the means by which the infinite and invisible becomes manifest. The narrative says, in effect, “This is the beginning of civilization. This is what translated us from a rabble into an organized, civilized, God-fearing people with a respect for law and order, which likewise came from God.”

This episode with the tablets is such a powerful story it has passed into the language: we say, “It’s written in stone.” It is identified with the very practices and beliefs that take us from being pre-civilized to being civilized. And the fact that the writing in stone is by the finger of God rather than a stylus pressed into soft clay is in itself an acknowledgement of the power and majesty of the written letter and the written word.

As a side note, the Exodus story also highlights the notion that writing exists to manifest the force of law—which, by the way, has been a weapon of inequality and injustice when oral societies have come up against more powerful writing societies who denied them rights based on their lack of documentation.

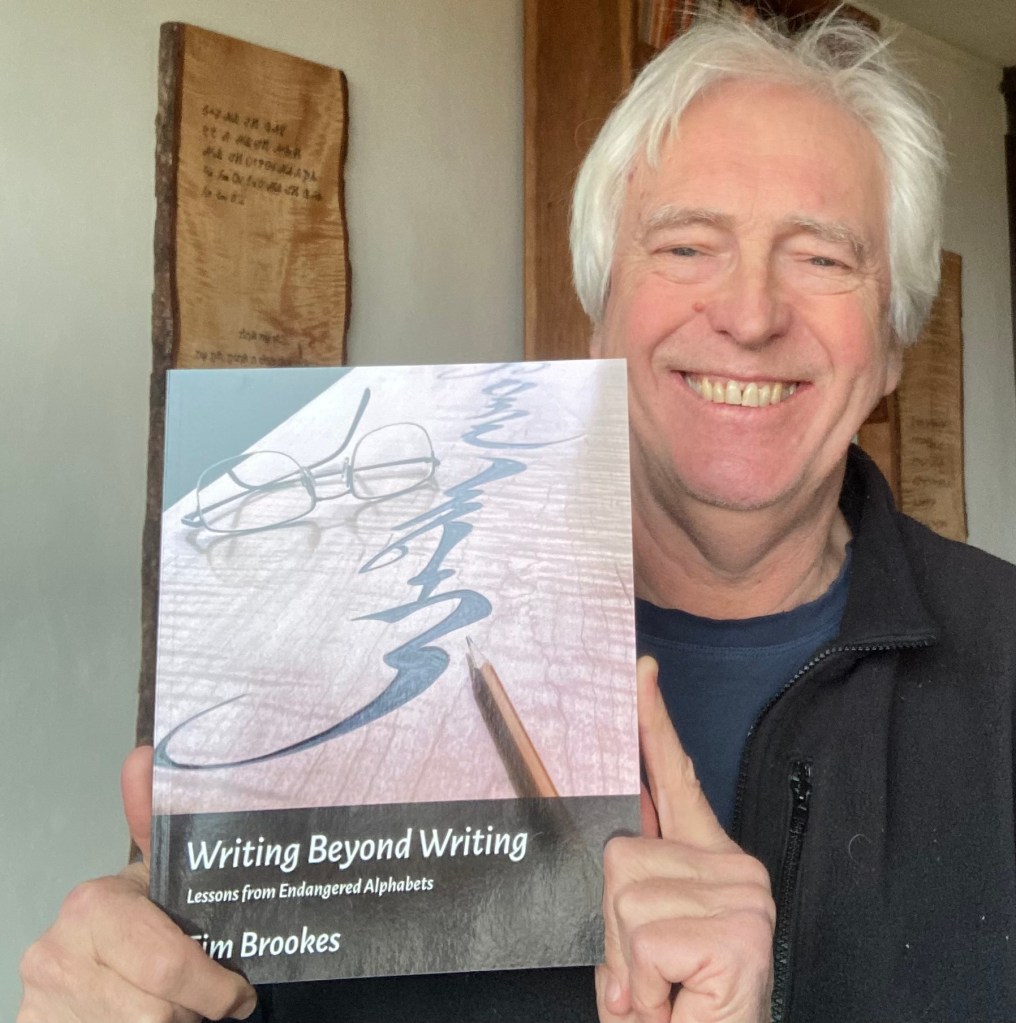

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.