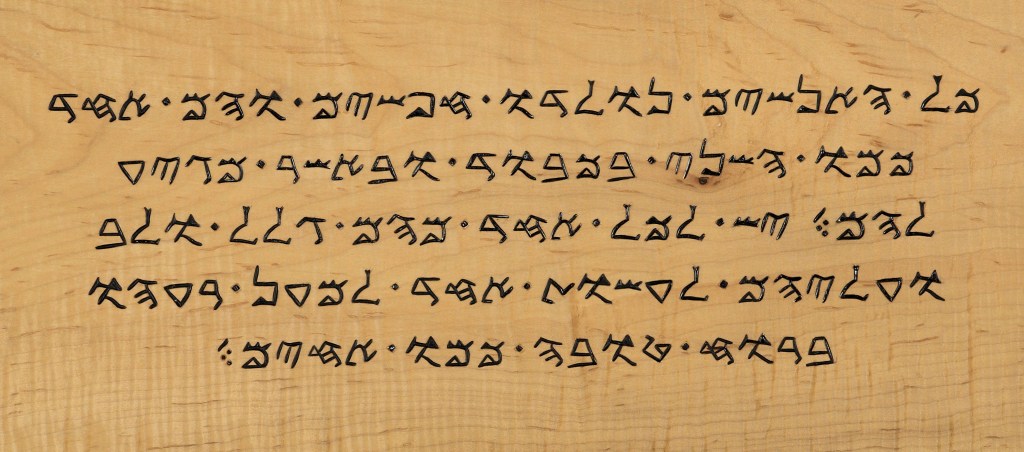

Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Samaritan. Carving and photo by the author.

During the current catastrophe in the Middle East, it may be reassuring to hear a story of survival.

Let’s go back two thousand years to the region confusingly called the Holy Land—confusing, because it was (and is) considered holy by several faiths, one of which was the Samaritans of Samaria.

The first-century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus wrote:

Now as to the country of Samaria, it lies between Judea and Galilee…and is entirely of the same nature with Judea; for both countries are made up of hills and valleys, and are moist enough for agriculture, and are very fruitful. They have abundance of trees, and are full of autumnal fruit, both that which grows wild, and that which is the effect of cultivation. They are not naturally watered by many rivers, but derive their chief moisture from rain-water, of which they have no want; and for those rivers which they have, all their waters are exceeding sweet: by reason also of the excellent grass they have, their cattle yield more milk than do those in other places; and, what is the greatest sign of excellency and of abundance, they each of them are very full of people.

(The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Macropaedia, 15th edition, 1987, volume 25, “Palestine”, p. 403)

The Samaritan family tree is very old, and has deep roots. Perhaps the first writing system to see widespread usage around the Mediterranean was the Phoenician alphabet, the script of a great trading empire. Phoenician was adopted (and adapted) by the Ancient Greeks, and as such, is ultimately the ancestor of the Latin alphabet used for these words. Another variant, perhaps 3,000 years old, has been dubbed the “Paleo-Hebrew” alphabet. But while the Jews migrated to writing with the Aramaic alphabet (the second great international script) around 2,500 years ago, their neighbors the Samaritans did not.

One theory is that the destruction of the First Temple and the exile of educated Hebrew speakers to Babylon caused Hebrew to commingle with Babylonian; another suggests that when the exiles returned to Judah they found it a Persian province where Aramaic was the official script. The Samaritans, having suffered no such exile, regard themselves as the true descendants of the sons of Israel, and their alphabet as the ancestral Hebrew script — a contentious position, given the power of writing as an iconic system, and one that did not make them popular with the Jews.

By the time of Christ, the two neighbors loathed each other. The entire point of the parable of the Good Samaritan is that it’s not the priest or the Levite, both representatives of the Jewish religious hierarchy, who help the mugged man – it’s the hated and despised Samaritan who gives first aid and puts the victim up at the nearest inn. “Which of these three was his neighbor?” Jesus asks, neatly making a point about both spiritual integrity and local hostility.

This idyllic pastoral life did not survive long.

Starting around 474, tensions arose between Samaritans and Christians. The Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno is said to have persecuted the Samaritans without mercy, and a series of revolts, violent in themselves and violently suppressed, continued for a century, reducing the Samaritan population from about a million to a couple of hundred thousand.

According to the historian Wikipedius, during the early Islamic period, the arrival of large numbers of Muslims resulted in waves of conversion to Islam “as a result of droughts, earthquakes, religious persecution, high taxes, and anarchy.” By the twelfth century, one visitor estimated that perhaps as few as 1,900 Samaritans were left in Palestine and Syria. Further pressures and conflicts continued to reduce their number, and by the start of the twentieth century only four families, numbering about 120 people, still spoke and wrote Samaritan.

Yet the Middle East communities know better than most how to survive in an adverse environment. As of 2022, the community stood at around 874 individuals, divided between Kiryat Luza on Mount Gerizim and the Samaritan compound in Holon.

Wikipedius continues that there are also a significant number of growing communities, families, and individuals who are not indigenous to the Holy Land currently known around the world who identify with, and observe the Samaritan tenets of faith and traditions. The largest community globally, the “Shomrey HaTorah” of Brazil, reportedly has some 20,000 members.

Further reading:

You can subscribe to the Israelite Samaritan newspaper at https://www.israelite-samaritans.com/samaritan-newspaper/ and order Benyamin Tsedaka’s commentary on the Torah at https://www.israelite-samaritans.com/books/torah-commentary/. His book Understanding the Israelite Samaritans can be ordered at https://www.israelite-samaritans.com/books/understanding-israelite-samaritans/.

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.