Topographic map in the Bamum script from early 20th-century Cameroon. Image courtesy of the Incunabula Library.

Creating a new script for an indigenous people during a colonial era is a two-edged sword.

The desire to claim and assert one’s cultural identity may provide the driving force that sustains an author through the long, hard work of creating a writing system, and it may also be the force that makes the resulting script popular. The colonial authorities, though, may well not want their subjects to develop a sense of their identity and self-respect, and in that sense, the more successful an indigenous script is, the more dangerous it may be, initially to those in authority, but then to the creator(s). We know of at least four script creators who were killed for their troubles, and another two who were essentially driven to their deaths.

One of the most remarkable of these creations, the Bamum alphabet, fell prey to its own success.

Starting around 1896, twenty-five-year-old King Ibrahim Njoya of the Bamum Kingdom in Cameroon invented a writing system for his people’s language called a-ka-u-ku, after its first four characters. He is said to have articulated this quest in an extraordinary observation, one that is one of those truths that are unlikely to occur to a dominant culture, but which minority or subjugated people understand instantly: that a people will never be free until they can write their own history in their own language and script.

Many indigenously-created scripts have had their origins in a dream, vision, or revelation, and Bamum provides a wonderfully vivid example of the advent of literacy as seen from the viewpoint of those who previously did not read or write, and who see writing itself as a gift of divine origin. As he himself told the story:

“When King Njoya was asleep one night he had a dream. A man came and before him saying: ‘Oh King, take a wide, flat piece of wood and mark on it a man’s hand. Then wash the board and drink the water.’ The king took a plank and made a mark as the man directed, and handed it to that man who also made a mark thereon and returned the plank to the King. In the dream there were many people sitting around, all schoolboys, and they had paper in their hands. They all made marks thereon and passed on what they marked to their neighbors.

“When it was daylight the King took a wide plank and marked thereon a man’s hand. He then washed the plank with water and drank it, as the man in the dream directed. The King now summoned many of his courtiers and told them to mark out many things and to give names to all these things so that the result would be a book. In this way man’s speech could be inaudibly recorded.”

The Australian anthropologist Piers Kelly observes, “The imagery is telling. In many regions of Africa a well-established healing ritual involves writing Quranic verses on wooden slabs or plates that are then washed off with water to be consumed by the patient. These rites do not require the participants to be literate in the Arabic script: it is the body itself that must read the sacred text without interference.”

Awaking, Njoya re-enacted the ritual before beginning work on a script for his native language of Bamum. With the help of advisors, he drafted over 1000 pictographic characters that were intended, at first, to represent objects and actions. Trying a different approach, Njoya and his team completed a table of 465 syllabic characters that over the next fourteen years went through six revisions until 1910, when it stabilised at 80 characters.

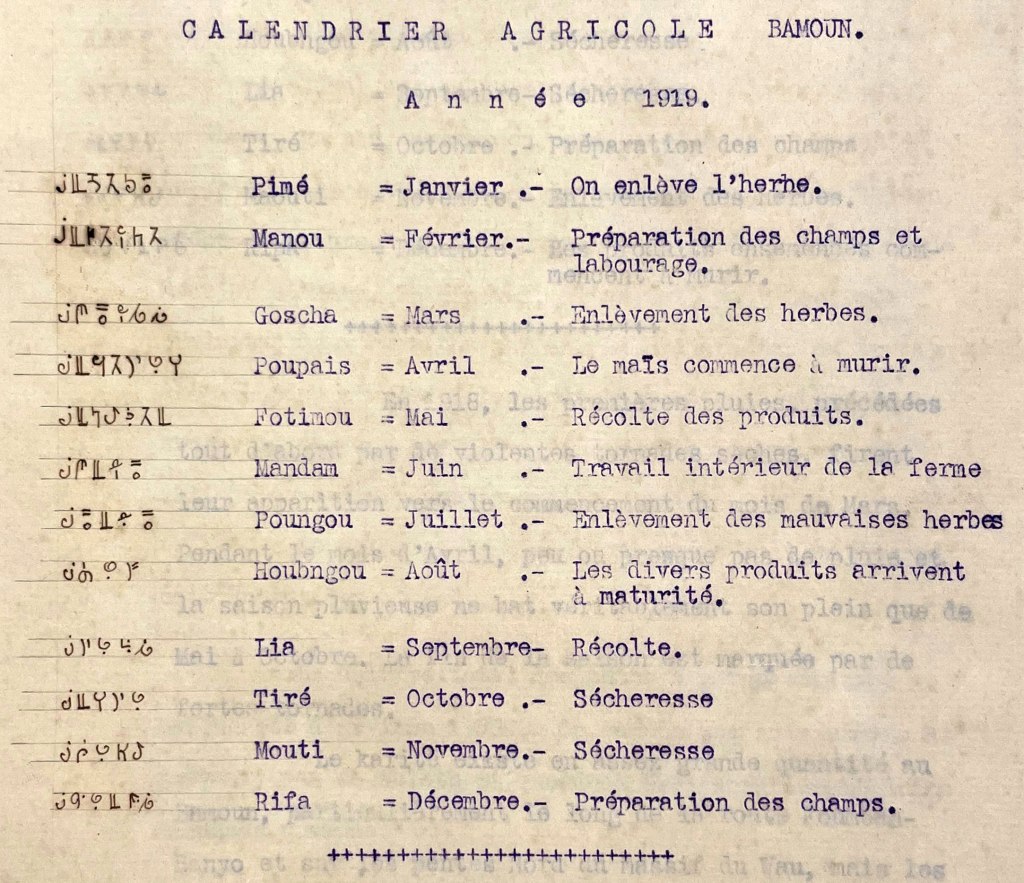

Using this script, he wrote a history of his people, a pharmacopoeia, a calendar, maps, records, legal codes and a guide to good sex. He built schools, a printing press and libraries; he supported artists and intellectuals. This seems to have been all well and good in the eyes of the local colonial power while Cameroon was under German control, but when the French took over part of the country after the German defeat in World War I, they manoeuvred Njoya out of power, smashed his printing press, burned his libraries and books, tossed out sacred Bamum artefacts and sent him into exile, where he died.

When a person dies, though, a script may survive, even if it is not used. It’s like a seed: when the right conditions arrive, it may flourish. Despite Njoya’s death and the almost complete suppression of the a-ka-u-ku syllabary, a century later the first coordinated efforts to revive it have begun. The current king, amazingly, wrote his thesis (on the cultural importance of his grandfather’s script) at St. John’s University in New York under the tutelage of Konrad Tuchscherer, one of the world’s leading experts in West African scripts, and the first book of poetry in the Bamum language and script was published in 2023. Watch this space.

Agricultural calendar in French and Bamum. Image courtesy of the Incunabula Library.

Further Reading:

Images from Bamum: German Colonial Photography at the Court of King Njoya, Cameroon, West Africa, 1902-1915 by Christraud M. Geary

Paperback – June 17, 1988

Publisher : Smithsonian; First Edition (June 17, 1988)

Language : English

Paperback : 144 pages

ISBN-10 : 0874744555

ISBN-13 : 978-0874744552

Item Weight : 1.38 pounds

Dimensions : 8.5 x 0.75 x 10.25 inches

L’Œuvre d’Ibrahim Mbombo Njoya, Sultan Roi des Bamum (French Edition) by Youssouf N’Ka

Paperback – May 24, 2018

Publisher : Edilivre (May 24, 2018)

Language : French

Paperback : 178 pages

ISBN-10 : 2414184299

ISBN-13 : 978-2414184293

Item Weight : 9.4 ounces

Dimensions : 5.28 x 0.41 x 8.03 inches

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.