Zhuang Musicians in Longzhou. Source: Wikipedia

Those of us from Western Europe and the Americas use a script that is so widely used we barely recognize it as a script. In fact, we often refer to it as “the” alphabet, as though there were only one. For us, our script is writing itself; most of us have no idea that in much of the world individual cultures have their own scripts, or that most educated people routinely use multiple scripts every day.

So let’s leap from that blithe universality to something so local, so specific, we are likely tempted to regard it not only as an aberration, but not really writing at all. Let’s leap to China, for example, and examine two scripts that are not only very, very local geographically but even more local in terms of purpose. They are used, in fact, specifically in songbooks.

In the Journal of Chinese Writing Systems 2023, Vol 7(2) 79–85, Professor Bojun Sun writes:

In the year 2009, [a] handwritten songbook was found at a Zhuang Village in Babao Town of Guangnan County, Yunnan Province. After 2018, a research group of the “Investigation and database establishment on newly discovered ancient writings of ethnic minorities,” led by Li Jinfang, launched another investigation in Babao Town, when 802 unduplicated symbols were found on shoulder poles, on bamboo tubes, on bottle gourds, and on scabbards, in which there were 26 symbols same or similar to those in the Poya Songbook.

The Poya Songbook, from the little we can gather, is a very local Zhuang script, for a very specific and extremely compressed purpose. It was found in Poya Village of Funing County, Yunnan Province, in the form of a document in which there are 81 single pictographs written on a piece of cloth inspiring people to recall the corresponding 81 Zhuang songs. The pictographs mimic the appearance of moon, person, grain, duck, fish, and bird.

In the Journal of Chinese Writing Systems 2023, Vol 7(2) 79–85, Professor Bojun Sun writes: “We see that the Poya Songbook, representing a complete song with many sentences by only one single pictograph, is also identified as the bud of script by Zhou Youguang in his inscription on a monograph (Liu, 2009), meaning that the pictograph is a kind of script germination. As an extreme example, the Poya pictograph represents a full song given below.”

Rogfek dihlawz raez, gaeqgae dihlawz rwenh, gaeqdwenh dihlawz haen, mbauqzaem dihlawz og, ogrok buxlawz fwen, hawj saemmwen maiq luenh. saem gu luenh baenz yuz, saem gu fuz baenz zauq, fuz baenz zauq maex ‘em, saem gu vien rongzdoq, saem gu goj rongzdinz, ndihndiz mbin nwengz bix.

“Where the partridge trills, where the kingfisher romps, where the pheasant crows, where the guy comes, there who is singing outside? The song made the girl’s heart pound. The mind is excited like the boiling oil, like the branches and leaves following the wave, like the floating grass.”

And in fact there’s one more reference, similar but different, from elsewhere in rural China.

In 1958 while conducting fieldwork in Yunnan, a professor came across a ricepaper booklet with strange script created from Chinese characters. This turned out to be a folksong booklet in Old Bai script. The booklet contained text that combined standard Chinese characters and “simplified” characters, though it’s not clear what that term means.

Let’s think about these scripts. In some cases a script that is so local is in fact intended as a kind of cipher, understood only by its creator and some confidants, or in fact by a group of confederates who want to communicate with each other without fear of being understood (and, perhaps, arrested). (See bilang-bilang, or the secret scripts invented by hermetics and alchemists)

That doesn’t, on the face of it, seem to be the case here. The situation with the Songbook Scripts seems more like Nüshu (a script that is hyper-local by both geography and gender) or Paraya (the script of the Dalits or Untouchables), because it has been invented by a minority that has so little freedom of travel and so little social status nobody else would want to learn it.

And yet, like many minority scripts, it may have a great deal to teach us. This may be the most difficult but important thing I write during my month of posts to you, and it’s the issue absolutely at the heart of Writing Beyond Writing, and that is this: nobody is trying to figure out what we mean when we say “writing.” We don’t even realize we’re not asking the question. And it’s a crucial question, because the future of writing is at stake, our writing and everyone else’s.

What I’ve discovered in wandering among the endangered alphabets is that different cultures mean very different things by the word “writing.” They use writing differently. They regard writing differently. They value writing differently. They have different rules for it, and it plays different roles in their lives, just as it plays different roles in our lives at different times, under different circumstances. At certain times, in certain places, it is sacred. At others, in others, it is magical, or divinatory. At still other, in still others, it is an art form, or a highly personal expression. In Yunnan Province, apparently, it can be musical.

Yet nobody is taking this extraordinary complexity, so close to the human heart and mind, seriously. For example: might it not be a fascinating opportunity to study the Songbook Scripts to see what they have to tell us about writing—because nothing reveals more clearly how we understand writing than when we ourselves try to invent it?

Yet the very scholar who discovered and described the Songbook Scripts describes them as “primitive.” This has been, and continues to be the ailment that plagues writing: we are too caught up in the belief that writing can be more or less evolved, more or less superior, and we have too long a tradition of taking what we consider to be inferior or primitive and tossing it into a corner.

The original argument for studying endangered languages, back in the 1990s, was not that they were important to the people who spoke them—that wouldn’t come until later. It was that we could never hope to fully understand Language itself unless we studied it in all its forms and varieties. Studying the Indo-European languages, as was the tradition, taught us only about Indo-European languages, not about Language itself.

I’m making the same case for Writing. We will never understand Writing just by studying the mainstream scripts and saying the rest are not important. What does the Mandombe script, which seems to be made up of a series of bricks from a wall, tell us about Writing? What does the Ogham script, scratched along the vertical vertices of stones, tell us about Writing? And what do two scripts used only for recording songs in two villages in rural China tell us about Writing?

I invite you to read my book and then let’s start the discussion.

Chinese Ethnic Minority Oral Traditions: A Recovered Text of Bai Folk Songs in a Sinoxenic Script by Jingqi Fu and Zhao Min with Xu Lin and Duan Ling

Hardcover ISBN: 9781604978957

Paperback ISBN: 9781638570424

Pages 426

Date: November 13, 2018

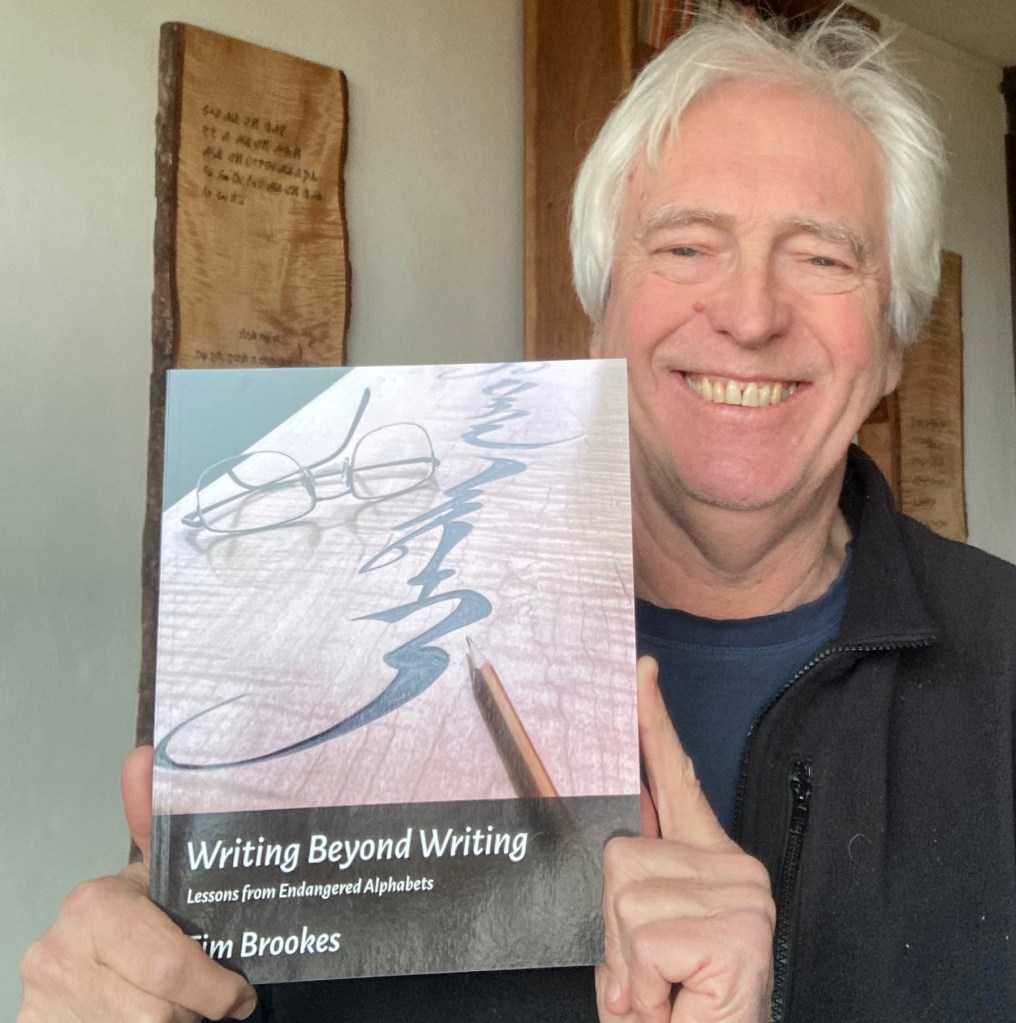

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.