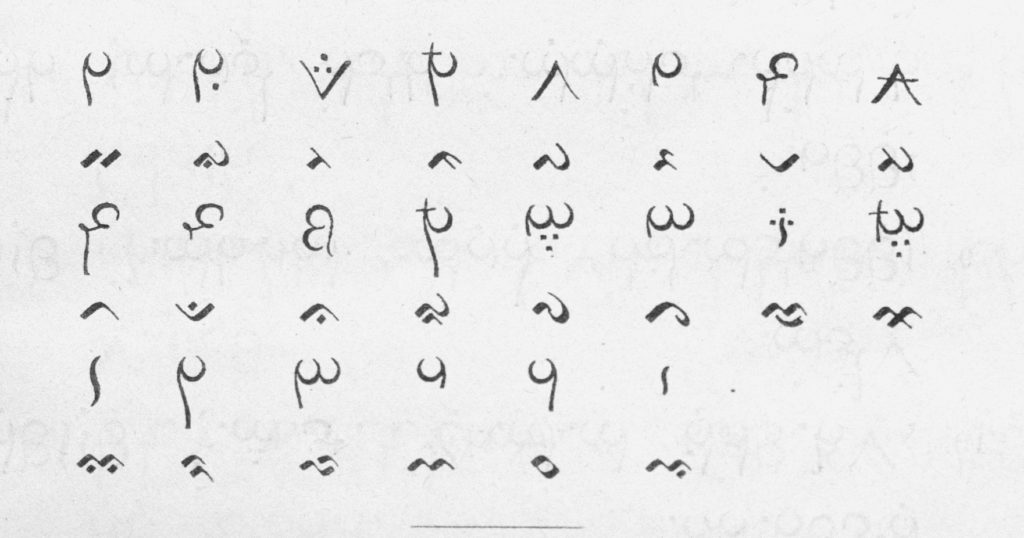

A table of Buginese cypher script with equivalent in standard Buginese script cited by B F Matthes in his book “Eenige proeven van Boegineesche en Makassaarsche Poëzie”, 1883. Source: Wikipedia

In a sense, every script is a code, comprehensible to some, incomprehensible to those who don’t know its workings.

We tend to think that writing is intended to be read and understood and, by extension, that it should be legible and comprehensible to anybody who speaks that language. This is only one conception of writing. Like many of our beliefs about writing, they are beliefs that come from how we use writing now- and by we, I mean we in the privileged West.

In fact, there are many instances in which writing has been used deliberately not to be understood, or not understood by everyone, or not understood by people outside a specific group. And if we think of writing as being an act of dedication and labor that has value and importance, then anything that is important to us may be something that we want to share, but equally, it may be something that we don’t want to share.

In Europe, 400 years ago, we see this in the writings of the Alchemists. Not only did the Alchemists use turns of phrase that had specific meanings to them, but were opaque or incomprehensible to outsiders, but they also used symbols–symbols that fit into a symbol system that they understood, but wouldn’t be understood by others, and among those symbols were ones they used for writing.

The Elizabethan astrologer, alchemist, physician and spy Dr. John Dee created his own writing system, the Enochian Alphabet. The alchemist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa created the Celestial Alphabet, also known as Angelic Script.

This makes perfect sense when you realize the Alchemists were walking a fine line suspended a long way above ground. They believed they were trying to discover the most powerful forces in the Universe; and while on the one hand they wanted to record their processes and discoveries and share them with those of similar high intent, they were very well aware that if their work fell into the hands of the ignorant and the uninitiated, they might misunderstand it, misrepresent it, and/or misuse it in catastrophic ways.

Nowadays, we don’t tend to think of writing in these terms, but that’s also partly because we have assumed a kind of devaluation of both the act of writing and content of writing–simply because virtually everybody in the educated West can write, and because we use writing for the most trivial purposes, as well as the most intentional, exalted or important. And also because we have electronic encryption.

A writing system can also become a code in a tragic way: when a culture suffers constant reverses of fortune and the number of people who use their script steadily dwindles, the script becomes a code simply because nobody outside that community has the means of or the interest in learning it. And that in itself may be reason enough for authorities to ban it. Eventually it becomes a code against itself: if there are two villages and only one person in each can still read and write their traditional script, the notion of a standard or authoritative version becomes impossible, and each person’s version, which is bound to be full of idiosyncrasies, becomes the closest thing to a standard as is possible. The script, in a sense, starts to break apart.

On a lighter note, the script-as-code can be fun. The deliberate hidden nature of a writing system actually enjoyed a culture-wide flourishing in the Dutch East Indies in the 19th century, when entire books would be written in a kind of écriture à clef, which the avid readers would then try and sort out, and understand, and translate, and then presumably boast to their friends that they had figured it all out.

My favorite alphabet code, and my favorite alphabet code creator, also came from the Dutch East Indies.

The Lontara Bilang-Bilang script is or was a deliberate interweaving of the Lontara script of Sulawesi and an ancient Arabic number-substitution code, and it has been used for both poetry and espionage.

Christopher Ray Miller writes: “This script is derived from an Arabic “abjad” cipher [that] takes as its basis the numeric values of the Arabic letters in their old order similar to Phoenician, Aramaic and Hebrew. Each letter in the cipher is replaced by the corresponding Hindu-Arabic numeral, which stops above the baseline for 1-9, touches the baseline from 10 to 99, crosses the baseline for 100 to 999, and crosses with an added curl below for 1000 and up.”

In other words, you see a number and convert it to a letter.

The bilang-bilang cipher is still used in word games and poetry, with an audience being asked to figure the correct pronunciation of a seemingly meaningless poem and reveal the poem’s hidden message.

The extraordinary story of bilang-bilang and its relationship with the Bugis people and their script, however, cannot be told without the story of Colliq Pujie, whose role in Bugis literature is even greater than that of any single figure in English — a fact that is all the more remarkable for her being a woman.

Colliq Pujié (or, to give her her full name, Retna Kencana Colliq Pujié Arung Pancana Toa Matinroé ri Tucaé) was the daughter of La Rumpang, King of the Kingdom of Tanete, now the Barru Regency in South Sulawesi. Born in 1812, she grew up at a time when her island was still struggling against the Dutch to achieve autonomy. Her father entrusted her not only with an education but with the running of royal affairs.

She did so with a possibly unique feat of linguistic subversiveness: in order to communicate in secret with others in the Bugis resistance, she began incorporating bilang-bilang characters into the Bugis script. Because these characters were numbers, which were not only incomprehensible to the Dutch but appeared to have no meaning when embedded in a text, they had a fascinating hidden-in-plain-sight quality, and became woven into the Bugis-Makasar script.

Linguist, historian, classicist, resistance fighter, editor, poet, diplomat, she eventually died in the process of writing out and editing La Galigo, the great 6,000-page, twelve-volume epic poem of Bugis literature, one of the longest epics in the world. The text, by the way, is not merely an epic or mythic poem, but each volume is thought to contain the spirits of the characters: before it is open and read aloud, it must be preceded by ritual that may include the burning of incense, and the sacrifice of a chicken or goat.

La Galigo

https://en.unesco.org/memoryoftheworld/registry/467

Illuminations: The Writing Traditions of Indonesia

by Ann Kumar (Editor), John H. McGlynn (Editor)

Publisher : Weatherhill; First Edition (January 1, 1996)

Language : English

Hardcover : 297 pages

ISBN-10 : 0834803496

ISBN-13 : 978-0834803497

by Donald C Laycock, Edward Kelly, et al.

Publisher : Weiser Books; Illustrated edition (September 1, 2001)

Language : English

Paperback : 288 pages

ISBN-10 : 1578632544

ISBN-13 : 978-1578632541

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.

One thought on “#EndangeredAlphabets: When Alphabets Are Codes”