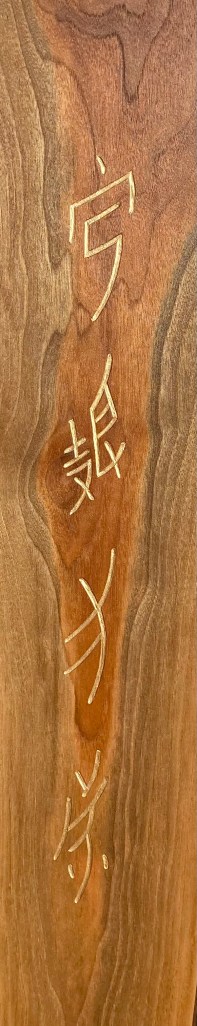

“Thank you all” written in the Nüshu syllabary. Photo and carving by the author.

Over the past decade, my research for the Endangered Alphabets project has found scripts that are exclusively sacred or spiritual, others used only for magic and divination, some employed solely for accounting and bookkeeping, some even for notating songs.

Writing, then, can be remarkably specific in its usage—and its tone. Asking myself whether any script in the world was used only to convey a particular emotion, I found myself thinking of two, both of them unusually gender-specific.

The better-known is Nüshu, literally “women’s writing,” a script used in a very limited area of Jiangyong County in Hunan province, China, apparently developed several centuries ago and used exclusively by women.

The linguistic historian Wikipedius writes: “Before 1949, Jiangyong County operated under an agrarian economy and women had to abide by patriarchal Confucian practices such as the Three Obediences. Women were confined to the home…and were assigned roles in housework and needlework instead of fieldwork, which allowed the practice of Nüshu to develop.” There was a deep connection between the script, fabric, and manual skills—so much so that Nüshu was not only written, but embroidered.

Nüshu was developed to express emotions that were inconvenient or even unacceptable to the orderly regulation of human life, and as such, these songs represent an entire panorama of concealed emotion. Mothers losing daughters, daughters losing mothers, sisters losing each other – a social web so torn, so desperate, it needed a secret script to recount such emotional weight.

Given the appalling limitations on women’s expression, freedom of action and freedom of movement, it’s hardly surprising that many Nüshu works were a way for women to share their sorrows within their community. Some Nüshu works were “third day missives”—cloth-bound booklets created by “sworn sisters” and mothers and given to their counterpart “sworn sisters” or daughters upon their marriage. They wrote down songs in Nüshu, which were delivered on the third day after the young woman’s marriage, expressing their hopes for the happiness of the young woman who had left the village to be married and their sorrow for being parted from her.

Nowhere was this unsettling combination of celebration and grief more evident than in the wedding tradition in which—given that after the ceremony, they may never see each other again—mother and daughter wind a marriage scarf together during three days of constant crying, sometimes stylized into song. The resulting tear-soaked scarf served as a link between mother and daughter.

Equally sad is the Lota script for the Ende language of south central Flores in Indonesia, a script that only survives, if it survives at all, to convey sadness.

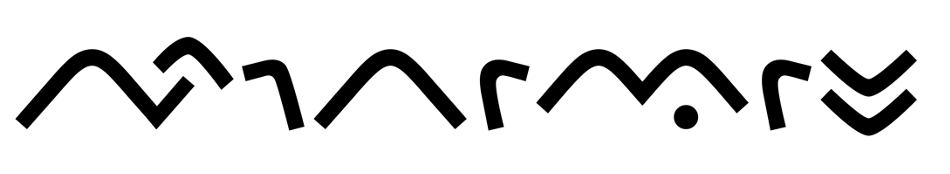

“Lota Ende” in Lota Ende script. Type design by Aditya Bayu Perdana.

Let’s let Maria Matildis Banda of the Faculty of Letters, Udayana University, Denpasar, Bali, take up the tale in her article “Lota Characters in Ende, Flores.”

The script may have arrived with Islam, something more than a century ago, but its use has dwindled steadily in recent decades. A research team in 2007/2008 found it “highly difficult” to find anyone who was able to read it; a further investigation in 2013 found only one person.

The local government of Ende and related institutions have not paid any attention to the existence of the Ende characters and manuscripts since 1991, and, she concludes, “It can be stated that now the lota Ende characters and manuscripts are ‘getting extinct’ if not ‘having been extinct.’”

This would be sad enough, but in fact the script, even more than Nüshu, is, or was, specifically used to carry sadness. Almost the only surviving use of Lota Ende is for poems called woi, or mourning poems, dealing with kinship relations, marriage, letters addressed to children, earthquakes, and circumcision.

Of these, the last to survive were used as part of the circumcision ritual.

“In general, the Ende manuscript is used when the ritual of circumcision is performed. First, those who perform the ritual ask the writer and reader [that is, someone who recites the poem] to write down the biography and the family situation of the boy who will be circumcised….

“Second, the relatives who take part in making the ritual successful come to the house of the boy whom will be circumcised bringing rice, sugar and the other things needed for the ritual. Before what they bring is given, the woi is recited. It generally contains the information why the relatives come, why the two families are related, the prayers that the ritual will be well performed, and the sadness they have ever had. The woi is always recited in such a sad tone that those who listen to it will cry. When such a ritual is performed, not only one family comes with their woi but more than one. In this opportunity, the listeners may evaluate which woi and reader are the best.”

That is, the saddest.

Inscribing Intimacy: The Fading Writing Tradition of Nüshu

by Dr. Orie Endo (Author), Dr. Hideko Abe (Translator)

Publisher : CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (August 12, 2019)

Language : English

Paperback : 188 pages

ISBN-13 : 978-1986828833

Heroines of Jiangyong: Chinese Narrative Ballads in Women’s Script

by Wilt L. Idema (Translator)

Publisher : University of Washington Press (December 26, 2008)

Language : English

Paperback : 192 pages

ISBN-10 : 0295988428

ISBN-13 : 978-0295988429

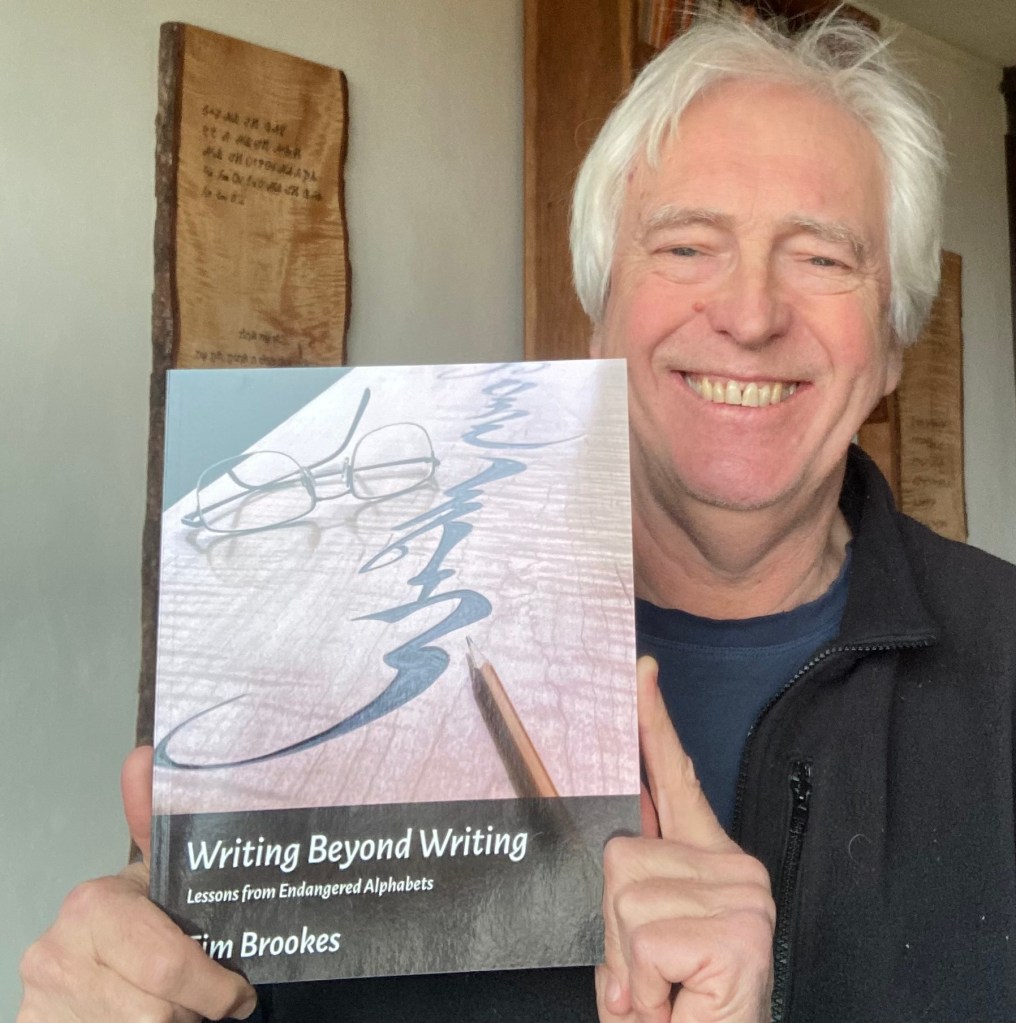

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.

One thought on “#EndangeredAlphabets: The Saddest Scripts”