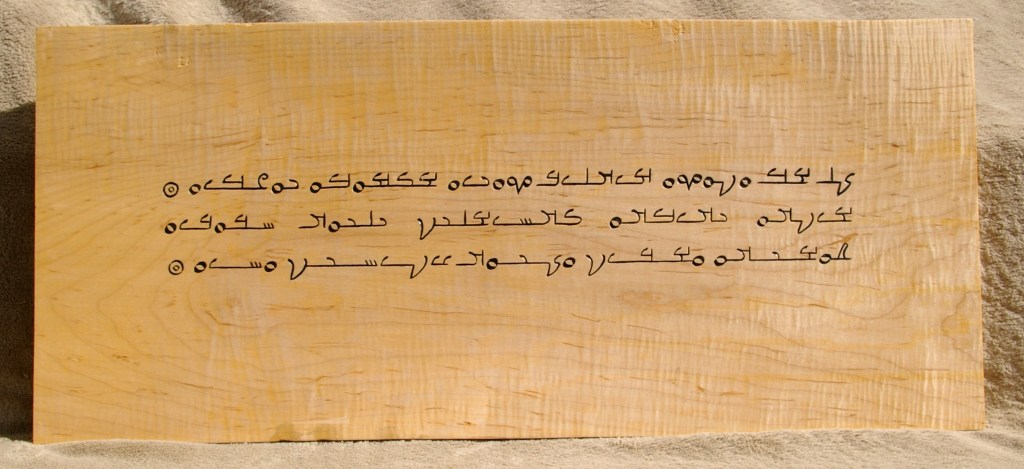

Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the Mandaic script. Carving and photo by the author.

Many, many of the world’s less-known scripts might change the way you think about writing, but none more so, I suspect, than the Mandaic.

The Mandaeans have possibly the most exquisite awareness of the importance of writing in the material and immaterial worlds, which they see as been united, in fact, by writing. For them, writing has, in effect, its own cosmology.

The Mandaeans are Gnostics. In fact, just as the word “gnostic” comes from the Greek word gnosis, meaning “knowledge,” the Mandaean word manda means “knowledge,” so both peoples referred to themselves as “the people of knowledge.” But in both cases, the words refer to a very particular kind of knowledge—that is, direct mystical apprehension of the divine, the ability to “know” God.

For the Mandaeans, this knowledge is intimately and inextricably connected to language, specifically to writing.

In Mandaic, each individual letter has its own mystical meaning. Moreover, the alphabet consists of the 22 separate functional letters of the Aramaic script—but then adds on another two letters to make the total up to 24, the number of hours from sunset to sunset, and therefore a mystical number. One of the added letters is a ligature of two characters, something like an ampersand in English; the final letter is simply the first letter, repeated, to give the impression that the alphabet is not linear and finite but, like the day, repeats every 24th time. A mandala of an alphabet.

The Mandaic alphabet invites us to think of writing as a miraculous transaction, analogous to the act of creation itself. In creating the physical universe, according to many traditions, the creator took a thought, something invisible and insubstantial, and made it visible, solid, habitable. Likewise, the act of writing takes an invisible, insubstantial thought and makes it visible, available to all, in a sense habitable.

The point, then, is not that Mandaic writing is a vehicle for transmitting information that can lead to enlightenment — it’s that each word, each letter, is in itself charged and radiant with enlightenment.

One of their origin stories concerns the structural development, so to speak, of the alphabet, which is seen not merely as a series of symbols in an arbitrary sequence but as a spiritual union, in which the first letter is also the last, thus repeating the sequence over and over infinitely.

The Thousand and Twelve Questions tells us that “each letter of the alphabet emanated from the last, starting with the circular A, the wellspring (aynā) from which all the letters emerged, to the letter B, and from the letter B to the letter G, and so forth, until 23 came into existence. Each praised and worshiped its predecessor, until they formed a new kind of structure, a wall spreading out to the left and the right from the L, the middle letter, because the L is the builder’s clay (or lebnā) that holds the left wing and the right wing of the wall together. Unfortunately, this wall stood only for itself, and could not support anything else, because the right and the left stood apart from one another.”

They soon realized that if they were to clasp their hands together and form four corners joining back to that circular letter A, they could build a solid foundation. Thus A became both the wellspring from which they emerged and the crown atop their heads. Only then did it become possible to name all things and speak every mystery, because language is not possible without “this indivisible republic of letters.”

Just think about that phrase. “The indivisible republic of letters.” That’s a perspective that sees writing as a living thing in itself, not just a set of arbitrary symbols.

In another of the Mandaean spiritual texts the divine creator himself, known as the Light King, sees writing for the first time and is so impressed and astonished he utters: “Who created these [letters]? I did not, therefore there must be one mightier than I!”

In other words, writing must have been created by a divinity mightier than the divinity who created the world itself.

You can see some fascinating examples of Mandaean type design at the website of Ardwan Alsabti; you can also follow the Society for Mandaean Studies on Facebook. The most remarkable book about the mandaeans by an outsider is The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Legends, and Folklore, by the astonishingly resourceful and intrepid Lady Elizabeth Drower.

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.