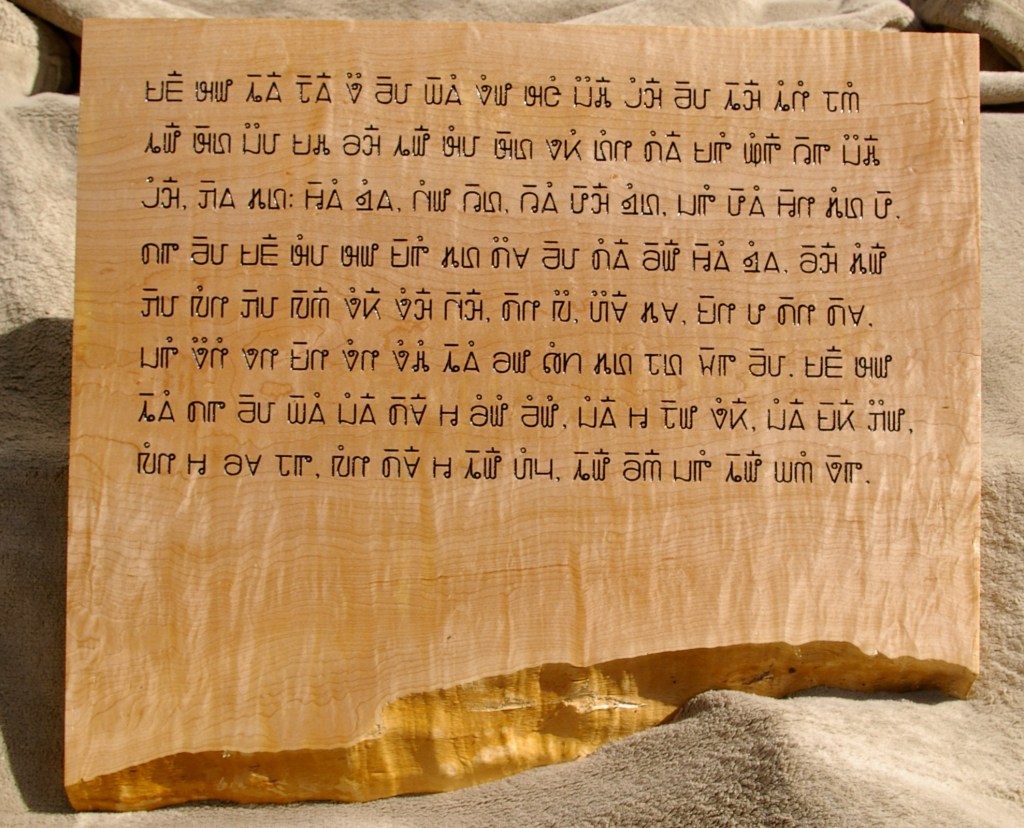

Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pahauh Hmong script

One of the most interesting discoveries results of research by the Endangered Alphabets Project is that fully half of all scripts in use around the world today were not adopted and/or adapted from an existing script—they were invented by an individual or group wanting to give their community its own writing system.

See, for example, Adlam, Cherokee and Hanifi Rohingya.

What this means is that those “family tree of writing systems” diagrams are incomplete and badly misleading, as they never include such “custom” scripts.

Worse, these new scripts or neographies are actually given remarkably little serious attention or respect by scholars.

One argument is that they are rarely successful, and in fact often fail to survive the death of their creator.

Let’s stop right there and examine the phrase “death of their creator.” Because the forces working against custom or indigenous scripts are so powerful that even if you create a script for your people’s culture and it is gleefully adopted and has the effect of bringing them together and giving them a greater sense of identity, history, purpose, and value, the very forces that were marginalizing your people may not be happy about your success.

They may make sure the new script is ignored, or not taught in schools, or not used in official publications. In extreme cases, the authorities may engineer the death of their creator.

In the ninth century, for example, in the Himalayas, King Sirijonga Hang of the Yangwarok Kingdom rose to power, subduing all the independent rulers and taking over as the new supreme ruler of Limbuwan, a nation of the Limbu people in what is now eastern Nepal. He built two big forts, one of which still stands. According to tradition he was responsible for another construction that stood the test of time, and unified all ten of the Limbu tribes: the Kirat-Sirijonga script.

According to Limbu folklore, he prayed to the goddess Saraswati for wisdom as to how to devise a script for his people, and in response she revealed the story of creation to him, written in the script.

The mythic or archetypical quality of this story is reinforced by the fact that, having apparently done its job, the script vanished. But its disappearance seems to have had an Arthurian waiting-to-return quality, for some 800 years later in the mid-eighteenth century, during a time of tension and upheaval in the region, then under the control of Sikkimese Bhutia rulers — in other words, just when it was needed — it was reintroduced by the Limbu scholar Te-ongsi Sirijong, believed to be the reincarnation of King Sirijonga.

He researched, revived and taught the Kirat-Sirijonga script, collecting, copying and composing Limbu literature, teaching the Limbu language and the importance of Limbu history and cultural traditions while at the same time preaching openness to other cultures and knowledge.

This work made him a cultural hero, but cultural heroes are also often threats. The Sikkimese Bhutia rulers ordered that he be tied to a tree and shot to death with arrows — possibly a cruel irony, as limbu means “archer.”

A great deal more recently, in 1959, an unlettered Hmong farmer and basket maker named Shong Lue Yang living in Vietnam announced that he had been inspired by God in a series of visions to create a written language for the Hmong, and, like Sequoyah with the Cherokee, set about converting first himself and then his people from non-literacy to literacy.

“The writing system presented the Hmong with a conception of themselves as united, sovereign, and spiritually redeemed,” John Duffy wrote in Writing from These Roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American Community. “[It] was more than a writing system for its users; it was, in addition, a guide to moral life and religious salvation.”

The effect of his invention was rapid and radical. Almost at once he took on a messianic status for the Hmong: his followers called him “Mother of Writing,” and looked to him for ethical and religious teaching and advice.

The nationalist feelings he was stirring up in the Hmong minority made the Vietnamese government uneasy. His supporters helped him avoid arrest, and smuggled him into Laos, but the complex and interrelated wars throughout the region and the outsider status of the Hmong meant that wherever he went, he was accused by both sides of aiding the other. Besides, no government in the region had any sympathy for a nationalist Hmong movement.

By 1971, his religious and cultural influence among the Hmong had grown simply too strong for the Laotian government’s liking, and soldiers were sent to assassinate him.

These script authors (and two others) were overtly and directly assassinated. Others suffered the same fate, a little less directly. The French colonial authorities were so disturbed by King Ibrahim Njoya’s efforts to bring energy and status to the Bamum people in West Africa, including creating a script for their language, that they drove him into exile, where he died.

Topographic map in the Bamum script. Image courtesy of the Incunabula Library.

Sheikh Bakri Sapalo, creator of the Oromo script for the Oromo, one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, was forced to flee to a refugee camp in Somalia, and died in the camp.

This is how powerful writing is, my friends—how much it means to a community that someone will risk death to create, use, promote and teach it, and how much it threatens authorities who want to keep a tribe, a community, a culture, under their thumb.

Writing from These Roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American Community by John M. Duffy

Publisher: University of Hawaii Press; Reprint edition (July 31, 2011)

Language: English

Paperback: 256 pages

ISBN-10: 0824836154

ISBN-13: 978-0824836153

Lo’ tù lu lulùre pon ntièn: From the Resilient Shadows (Des ombres résilientes)

Bamum poetry by Samuel Calvin Gbetnkom

Publisher : Athinkra (June 24, 2022)

Language : English

Paperback : 52 pages

ISBN-10 : 0981829422

ISBN-13 : 978-0981829425

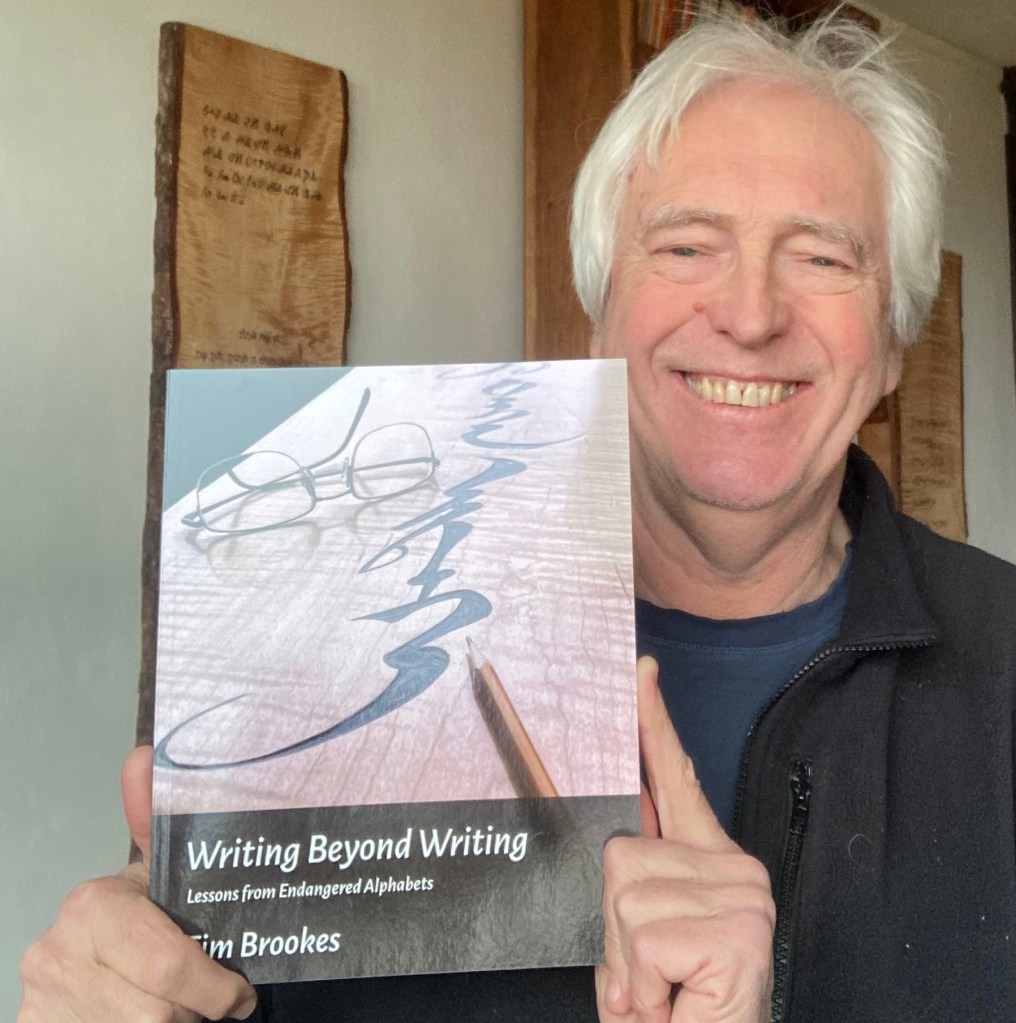

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.

Global Literature in Libraries Initiative is committed to publishing a diversity of thought. Individual posts are representative of each individual creator rather than GLLI as an organization.