“Save our language” in the Zaghawa language and the Beria script, in which each letter resembles a camel branding symbol. Carved by the author.

Right, let’s get this month going. Let’s head out into the fascinating world of Indigenous and minority scripts. And let’s start by talking about camels.

I’m trotting out camels, so to speak, to illustrate what I mean by the word “Indigenous,” especially in terms of writing.

“Indigenous” is often used to mean a culture or people that are local, undeveloped, even primitive, but to me it asserts a profound connection between a community and its place, its history, its geography, even its climate. And when it comes to writing, it’s hard to find a better example of this connection than in the Beria script developed by the Zaghawa people of Chad and Sudan for the Zaghawa language.

The Zaghawa inhabit one of the driest desert regions on the planet, and their livelihood and even their very lives depend on the camel. As such, the camel is as much a part of their culture, their history, their economy and their daily lives as the horse is to the Mongols. Camels are used not only as pack animals: the Zaghawa (and other cultures in the region) celebrate its importance with camel racing, and even camel beauty contests.

Camels being so vital, then, it is crucial to denote who owns which camels—and to do this, the Zaghawa (like ranchers in the American West) practice branding. A brand is, of course,a symbol, and a letter is another kind of symbol, so it’s not that much of a stretch when in the 1950s, a Sudanese Zaghawa schoolteacher named Adam Tajir created an alphabet for his people’s language whose characters were derived from the clan brands used for camels and other livestock. Its name is Beria, or sometimes the Beria Branding Script.

Beria has the two ideal qualities of Indigenous alphabets: it looks like nobody else’s script, and it displays its own specific cultural origins. A branding iron is essentially a metal rod of uniform thickness whose end has been bent into the shape of a particular symbol, and the Beria script has the same angular quality, the same uniform thickness.

It also has no ligatures—that is, each character is separate and individual. Handwritten scripts tend to show the lateral flow of the hand, the turn of the wrist; Beria, however – crisp, uniform, slightly industrial, almost geometrical – looks like a series of symbols to be stamped rather than written.

This script, though innovative and Indigenous in the best sense, turned out not to be ideal for representing the sounds of the Zaghawa language, as it was based on the Arabic script. Under the circumstances, perhaps it’s not surprising that the person who remedied its shortcomings was a vet. In 2000, a Zaghawa veterinarian named Siddick Adam Issa created a modified version of the Beria script, which he called Beria Giray Erfe (“Writing Marks”).

Even though the Zaghawa inhabit one of the poorest areas in the world, ravaged by decades of civil war, supporters of the script created a YouTube channel for reading and writing lessons in Beria. In 2019 AlSadik Sadik, a native of Darfur, became possibly the first person to try to raise the money needed to digitize an emerging script by crowdfunding:

I was born in … a small village in the Darfur region of Sudan, in 1987. As children, me and my friends were beaten just for speaking our own language. Since then, it has been a dream that I share with many others, to make it possible for us not only to speak Beria freely, but also to be able to read and write it!

I heard about his amazing initiative and carved the piece at the head of this column, to be a reward for any sizeable donation to the campaign.

This is a point I made in yesterday’s column, and I’ll illustrate over and over: that a script is the product and manifestation of its culture, and it embodies and displays the aesthetics, the values, the history and the beliefs, the materials, the tools, even the climate, that have shaped it. You can never sensibly discuss a script without its human context, just as you can never remove a script from its people without incalculable loss.

To date there are no books about the Zaghawa people in the Beria script, as far as I know, but thanks to AlSadik Sadik’s efforts there is a primer/photo-and-word book, not widely available.

Nor are there any books I can find about the wonderful symbiosis between the Zaghawa and their camels, though there are delightful videos about camel branding and camel racing in Oman, and the internationalization of camel beauty contests. There’s also a short video about carving the Beria script:

As for books, one possibility is Contes Zaghawa du Tchad: Trente-sept contes et deux légendes, collected by Marie-José and Joseph Tubiana, published in French and Arabic. Publisher : L’HARMATTAN (May 3, 2000) Paperback : 124 pages. ISBN-10 : 2738402518; ISBN-13 : 978-2738402516.

The Beria-English Dictionary does not use the Beria script, but is full of culturally rich translations, such as dabara: a blister, especially on a camel’s back after a long day of racing; dabo: the season between November and January, when the herds are dispersed toward pastures to the northeast, the grain is beaten and stored and the markets are more intensely frequented; and dabûrû: a camel that has not given birth.

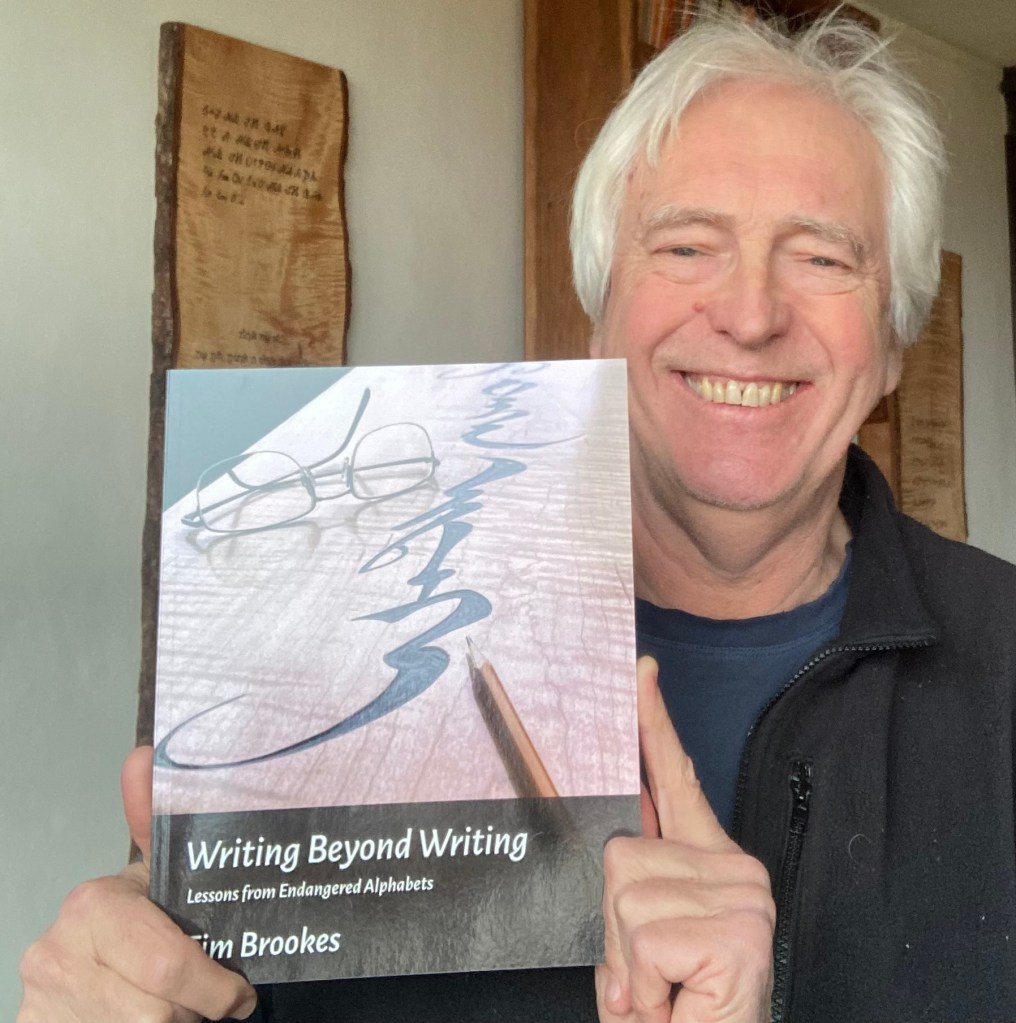

Tim Brookes is the founder and president of the non-profit Endangered Alphabets Project (endangeredalphabets.com). His new book, Writing Beyond Writing: Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, can be found at https://www.endangeredalphabets.com/writing-beyond-writing/.