Since its first articulation by scholar Rudine Sims Bishop, much has been written about the need for children’s books that are both windows and mirrors: books that allow children to see not only children different from them, but also to see themselves reflected in the text. Often used as an analogy to discuss the importance of diversity in kidlit, windows and mirrors—along with sliding glass doors—remind us that all children need books in which they can see themselves.

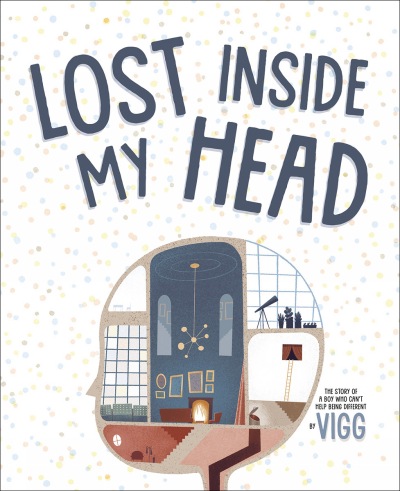

Written and illustrated by Canadian-born artist Vigg (website in French), Lost Inside My Head is an autobiographical look at growing up with ADHD. Originally published in French by Les éditions Fonfon, and released just last month in an English language translation by Orca Book Publishers, this Canadian #worldkidlit title is a needed representation of neurodivergence in children’s literature.

Vincent, our protagonist, sits at the breakfast table with his parents. At school today he has to recite a story his mother has helped him memorize. Everything is going smoothly until is it time to stand in front of the class and recite his story from memory. Nothing comes out. Nothing at all, except embarrassed angry tears and laughter from his classmates. Back in his seat, Vincent hides inside his head, waiting for his mom.

What went wrong? As Vincent explains, sometimes the Control Room in his head, with all its screens playing hundreds of movies all at once, is too much for him to manage. He leads the reader through a tour of his head: into the Living Room, where his friends from books and movies help him make sense of things, through the Light Room, where he feels smart and anything he works on is possible, and to the Chute for nasty words, where he tries to discard all the unkind things people say about him—that he’s useless, lazy, or a space cadet.

After the recitation incident, Vincent finds it hard to stop his racing thoughts, especially at night. But he has no problems focusing on a showing of Pinocchio at the movie theater, even recounting every detail of the movie to his mother afterward. Would school be easier if it was like a darkened and hushed movie theater? If there was only one thing on one screen? If that doesn’t work, perhaps the key is not making everything dark, but instead focusing on the light.

Vincent revisits the rooms in his head and decides to make some changes. Instead of trying to spend most of his time in the Control Room, he resolves to visit the Light Room more often, where he can see better, listen better, and find his voice.

Neurodivergent readers may very well recognize Vincent’s Light Room as a his place of hyperfocus, where creativity, interest, and focus converge. Persons with ADHD can indeed focus—if the proper accommodations are in place. Neurodiversity is about honoring differences in thinking, learning, and behaving and seeing those differences as normal variations in human experience. There is nothing wrong with Vincent; perhaps instead of memorizing and reciting a story in the front of the entire class (a task with somewhat questionable pedagogical applications), he could instead draw a picture to show his comprehension or maybe talk about the story one on one with his teacher, as he did with his mother when retelling the story of Pinocchio. Vincent and other children like him would fare better in the classroom if teachers used the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to change the environment and not the learner.

Translator David Warriner gives readers a highly readable text with great attention to detail; for example, the “not-so-nice” words that Vincent throws down the chute in his head are all translated, as well as the great wall of text representing the thoughts in Vincent’s head when his teacher makes him up front, right next to the window, in a well-meaning but misguided attempt to help him concentrate. At 72 pages, this is a longer picture book, and is better suited for children in primary or elementary school, or ages 6 and up.

While it is wordier than some picture books, the text does not overshadow the storytelling power of Vigg’s illustrations. His use of blank space is particularly compelling when representing Vincent’s isolation, or when he is unsure of himself. The physical book itself is somewhat oversized at 9×13 inches, the covers are sturdy, and the pages are of thick, sturdy paper; Orca Books has taken care to give us a quality book, both inside and out. Lost Inside My Head merits inclusion in school and public libraries, and would show ADHD children that they can do, and create, great things.

*Blogger’s Note: I am indebted to my dear friend LA Cox, a neurodiversity and disability scholar, for introducing me to neurodiversity and UDL. Thank you for giving me new eyes with which to see, LA.

Title: Lost Inside My Head

Written and illustrated by Vigg

Translated from French by David Warriner

Orca Book Publishers, 2023

Originally published as Ma maison-tête, 2020, Les éditions Fonfon

ISBN: 9781459835948

Awards: (for French edition) Governor General’s Literary Awards Finalist for French Language Illustrated Young People’s Literature, 2021; Canadian Children’s Book Centre Prix TD de littérature canadienne pour l’enfance et la jeunesse Laureate, 2021; Prix Harry Black de littérature jeunesse Laureate, 2021

You can purchase this book here.*

Reviews: Kirkus, School Library Journal, Canadian Review of Materials

*Book purchases made via our affiliate link may earn GLLI a small commission at no cost to you.

Klem-Marí Cajigas has been with Nashville Public Library since 2012, after more than a decade of academic training in Religious Studies and Ministry. As the Family Literacy Coordinator for Bringing Books to Life!, Nashville Public Library’s award-winning early literacy outreach program, she delivers family literacy workshops to a diverse range of local communities. In recognition of her work, she was named a 2021 Library Journal “Mover and Shaker.” Born in Puerto Rico, Klem-Marí is bilingual, bicultural, and proudly Boricua.